Summary of this article

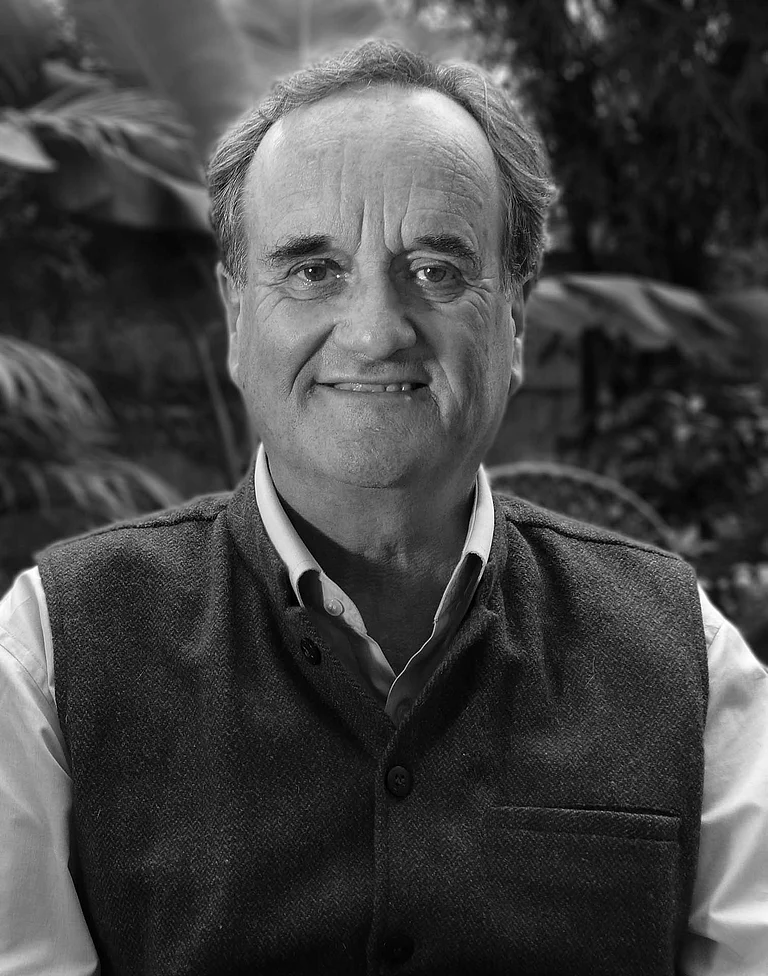

Mark Tully was widely remembered for his professionalism and moral courage, particularly for standing up to the BBC establishment when he felt journalistic values were being compromised.

At a time when India often bristled at foreign criticism, Tully emerged as a foreign observer who won trust by reporting with a deep understanding of India.

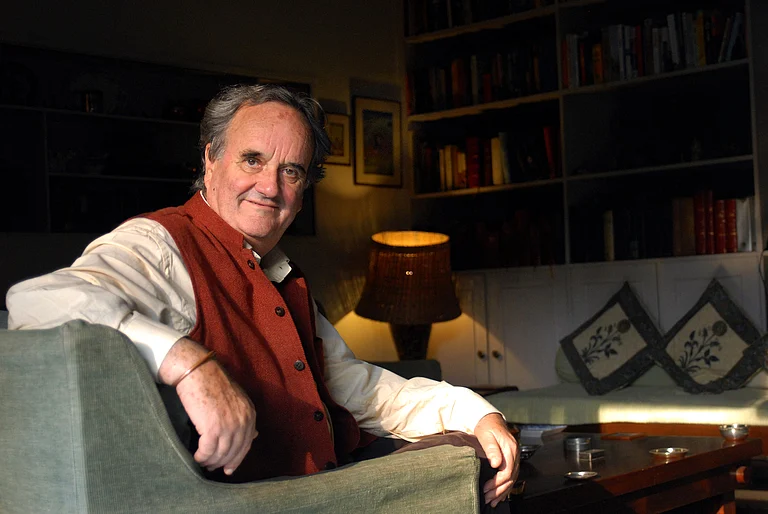

As the BBC’s face in India from 1964 to 1994, Tully chronicled defining moments of the country’s modern history with a distinct, non-haughty voice.

Nearly a century ago, a foreigner, an American historian named Katherine Mayo, wrote a book in 1927 called Mother India. It was a brutal catalogue of almost every wart on the Indian social and religious landscape. The book touched a raw nerve. There was outrage and anger. Mahatma Gandhi, of all people, led the chorus of denunciation, calling the book “a drain inspector’s report”. No foreigner, it seemed, was entitled to point out our defects and deficiencies. We will take offence.

Then came Independence. We were blessed to have a man called Jawaharlal Nehru at the helm. He was a self-assured leader and India, under him, was not easily troubled by the outsider’s critical observations. We knew what we were trying to accomplish, and took the outsider’s pinpricks and quibbling in our stride.

It was in the years of post-Nehru uncertainty that we rediscovered the Katherine Mayo syndrome. We bristled at the foreigner who was less than appreciative of our difficulties and dilemmas. The middle classes resented any outsider pointing out our moral hypocrisy. We took umbrage at a Nirad C. Chaudhuri or a V. S. Naipaul for being less than reverential towards our icons. We even denounced Satyajit Ray for showing “our poverty” just to win a little applause from the western elite. No foreign observer, correspondent or chronicler could get it right or satisfy us.

Mark Tully of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) was an exception to this streak of paranoia. So much so, his demise on January 25 was front-page news in many newspapers, a distinction that no Indian journalist has been deemed worthy of in recent years.

For nearly three decades, from 1964 to 1994, Tully was the BBC’s face in India. It is necessary to remember that this was the time when many people, in and out of India, regarded the BBC as the propaganda mouthpiece of the colonial interests in London. Tully’s challenge was to navigate through this widely felt distrust of the BBC.

And, he did an excellent job in reporting from India. This was a time, remember, when India crossed many milestones in its national journey—the 1971 Bangladesh War with Pakistan, the Emergency, the Punjab insurgency, Operation Blue Star, Indira Gandhi’s assassination, the anti-Sikh riots, the Bhopal gas tragedy, Rajiv Gandhi’s inglorious fall and violent death, and the demolition of the Babri Masjid—and Tully was telling the story to us as also to the outside world. He invariably set his piece in a tone and tenor different from the haughty voice that came easily to other foreign correspondents. To be sure, there were times when his reportage did not quite please the powers that be; yet it is remarkable that twice he was conferred with our high civilian honours—a Padma Shri in 1994 and a Padma Bhushan in 2005.

Perhaps the key to the acceptance and appreciation that Tully earned was because he did not come across as if he was pinning for the Raj. No hint of patronage or condescension. Unlike many other foreign correspondents reporting from India, Tully Saheb avoided sounding supercilious.

Rather, when he was critical of what we were doing to ourselves in politics or economy, he politely informed the listener that he was merely trying to judge us by the standards we have set for ourselves. It was inevitable that our political system and its operators often failed to meet those lofty standards. While a part of our ruling classes did resent that a foreigner was pointing out our deficiencies, the democratic temper of those times was sufficiently tolerant.

Because that was the age of the transistor, and Tully was a quintessential radio man, his voice became familiar to millions of listeners all over the subcontinent—thanks to the BBC Hindi Service. His voice was authoritative, words credible, and tone fair. He made the BBC not only a household word, but also a source of correct and factual reports.

After he resigned from the BBC in 1994, he chose to stay back in India. He became a familiar figure in Delhi’s social circuit. He was accepted in fashionable parlours, though he perhaps would reject the suggestion that he had been co-opted by Delhi’s Lutyens Elite. Yet, he would easily accept that he had become committed to India and its republican virtues and values. And, he was saddened by the unhappy turn India has taken in recent years.

He served India well by telling us a few harsh truths and we should be grateful to him for that candour and honesty. Even in his death, he turned out to be a kind of catharsis for the Indian media fraternity.

Almost every newspaper and journalist recalled his professionalism and moral courage in standing up to the BBC’s establishment when he thought that the London-based bosses were diluting journalistic values and ethics. In this outpouring of tributes, the Indian media fraternity was bemoaning its own surrender to authority, its own helplessness in living up to the Mark Tully standards of balance, honesty, trustworthiness, and credibility. This was Tully’s last bit of service for Mother India.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Harish Khare is a Delhi-based senior journalist and public commentator