Summary of this article

Bollywood children’s films faded as Hindi cinema prioritised family entertainment over children as a distinct audience.

Filmmakers and critics argue that Indian children’s cinema never fully developed a child-centric point of view.

OTT abundance has not replaced theatrical children's movies rooted in Indian childhood and imagination.

It is a Sunday morning in the summer of 2009. The school break is on, the heat has arrived early, and the house is quieter than usual. Parents are tempted to sleep in. Children are not. On the dining table lies a newspaper, folded open not to the headlines but to the television listings. Fingers scan columns with urgency. What films are playing today?

The answers come easily. Bhoothnath, Taare Zameen Par, Ta Ra Rum Pum, Toonpur Ka Superhero—films that acknowledged children as viewers who could feel deeply, without being constantly instructed. These were films that did not exclude adults but did not centre them either. That assumption of a child watching closely, listening, absorbing, no longer feels foundational to Hindi cinema.

Somewhere between rising ticket prices, the collapse of matinee culture, and the industry's comfort with the catch-all idea of "family entertainment, children's cinema slipped quietly out of the frame. Not with outrage, but with indifference."

Children as an Audience, not an Afterthought

There was a time when Hindi cinema recognised children as a distinct audience and not as a narrative device or an emotional shortcut.

Cable television played its part. Films like Taarzan: The Wonder Car (2004), Ferrari Ki Sawaari (2012), Bhoot and Friends (2010), and Abra Ka Dabra (2004) were aired over and over, growing familiar through repeat viewings rather than opening-weekend numbers. They were imperfect, often uneven, sometimes clumsy. But they spoke a language children understood—curiosity, fear, play, longing.

Today, that language feels largely absent. The easy explanation is commercial. A trip to the cinema has become expensive. For families, it competes with other forms of leisure. In an industry increasingly driven by scale and spectacle, children's films rarely promise returns that justify risk. But economics alone cannot explain the disappearance. What is more unsettling is the shrinking imagination around what children deserve to watch.

Looking Back In Time

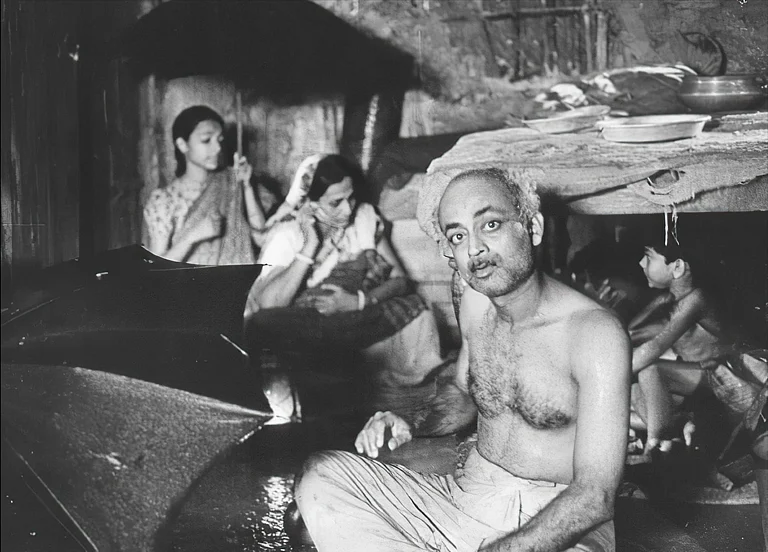

Long before children's cinema became a “risk category”, Satyajit Ray made a very deliberate choice.

Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) did not begin as a film. It first appeared as a story in Sandesh, the children's magazine founded by Ray's grandfather, Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury. Ray had grown up immersed in that world, where fantasy was not frivolous and humour carried moral weight.

By the 1960s, Ray was already celebrated for films marked by restraint and seriousness. Yet, he felt compelled to make something for children. According to his biographer Andrew Robinson, the impulse was personal. Ray wanted to make a film that his son could enter, without feeling alienated by grim realism.

Released in 1969 after a production plagued by financial constraints, Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) embraced magic, music , and moral clarity without flattening its characters. It was a critical and commercial success, winning the National Film Award for Best Feature Film in 1970.

Without announcing it as a manifesto, Ray demonstrated something Hindi cinema would later forget: children's films need not be marginal. They could be playful without being empty, imaginative without being simplistic, and artistically ambitious without losing audiences.

Nipped in the Bud

Filmmaker Amole Gupte, director of Stanley Ka Dabba (2011) and writer of Taare Zameen Par (2007), challenges the popular idea that Hindi cinema has "lost" children's films.

"For there to be a decline, there has to be a steady flow first," he says. "Children's cinema in India never truly blossomed."

Gupte argues that many films remembered as children's films were, in fact, adult stories filtered through children. "The gaze was rarely the child's," he says. "The child was present, important even, but the emotional centre belonged to adults."

This distinction matters. Internationally, children's cinema is defined by point of view rather than age-appropriate packaging. It asks what a child sees, fears, misunderstands, or imagines. In Hindi cinema, children are more often symbols of innocence, of correction, of the nation's future. Rarely are they allowed emotional complexity without explanation.

There is no single global definition of children's cinema. But across cultures, certain principles repeat. Children's films are not simplified adult films. They are not moral lessons disguised as stories. They are narratives that respect a child's intelligence, emotional range, and autonomy.

Film editor and writer Deepa Bhatia has spoken about how Indian cinema often mistakes accessibility for condescension. “We think talking down is the same as talking simply,” she observes. “Children can handle ambiguity far better than we assume.”

This becomes clearer when Hindi cinema is placed alongside other traditions. Iranian cinema, Japanese animation and European children’s films routinely explore grief, loneliness and moral conflict without underlining intent. Hindi cinema, by contrast, often softens or overexplains.

Adults first, Children later

A recent academic study by Yu Zhu of the London School of Economics, examining films like Taare Zameen Par (2007) and Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015), points to a recurring structure: the child’s suffering becomes a trigger for adult transformation. The emotional arc is completed when adults change, while the child’s interiority remains secondary.

The result is a cinema that appears child-centric but speaks primarily to grown-ups. This reflects a broader social attitude. Children are celebrated rhetorically, but rarely engaged with seriously.

Poet and filmmaker Gulzar has long pointed out this contradiction. In an interview with The Hindu, he said, “We say children are the future of the nation, yet our actions betray that belief.” The diminishing presence of libraries, playgrounds and cultural spaces mirrors the uneven investment in children’s cinema. Children are spoken for, rarely spoken with.

Why OTT hasn’t solved the Problem

Streaming platforms are often positioned as the solution. There is an abundance. Animation thrives. Algorithms recommend endlessly. On paper, the problem appears solved. In practice, however, it isn’t. OTT platforms offer volume, not intent. Children’s content is largely shaped by imported formats, dubbed animation and performance metrics. Live-action stories rooted in Indian childhoods remain rare.

Neha Jain, Film Pedagogy Head and Artistic Director of the School Cinema International Film Festival, has spent over a decade working with children and cinema through educational frameworks. School Cinema curates age-appropriate films for schools, followed by guided discussions that treat cinema as a tool for reflection rather than distraction.

For Jain, the issue is authorship. “When children’s content becomes purely algorithm-driven, it loses cultural specificity,” she has said. “What gets made is what performs, not what is necessary.”

Theatrical children's cinema once offered something streaming cannot replicate—a collective experience, a shared emotional rhythm. That sense of occasion is now fragmented. Viewing has become solitary. The child is no longer an audience member but a data point.

The Institutional Failure

If children's cinema ever had a custodian in India, it was the Children's Film Society of India. Founded in 1955, the CFSI produced over 250 films across languages. Many were imaginative, regionally rooted , and attentive to a child's inner life. Yet, most never travelled beyond limited circuits.

Actor and filmmaker Nandita Das, who served as CFSI Chairperson from 2009 to 2012, describes her tenure as rewarding but deeply frustrating. "I couldn't transform a 55-year-old organisation in three years," she says. "But I tried initiating changes that could outlast my time there." Her focus was on structural reform and quality over quantity. One outcome was Gattu, which became the first CFSI film to receive a proper theatrical release. "I hoped it would set a precedent," Das says. It did not.

Distribution remained the biggest failure. "There is a clear lack of age-appropriate alternatives," Das notes. "Much of what exists is either preachy and dull, or overly fluffy and sometimes even violent." She rejects the idea that meaningful children's cinema is unviable. "It is possible to make budget-friendly films that are engaging without being patronising," she says. "A children's film does not need to carry a message, but it must be responsible."

Responsibility, she argues, means recognising how deeply cinema shapes a child's emotional world. Good children's cinema connects with curiosity, adventure and wonder. "It helps children make sense of the world, while offering hope."

For younger filmmakers, the absence is personal. Mumbai-based filmmaker Hitarth Desai, who recently worked as an Associate Director on Netflix’s Jewel Thief, has consistently placed children at the centre of his short films. "I didn't set out to make children's films," he says. "I had stories to tell, and they happened to be from a child's point of view."

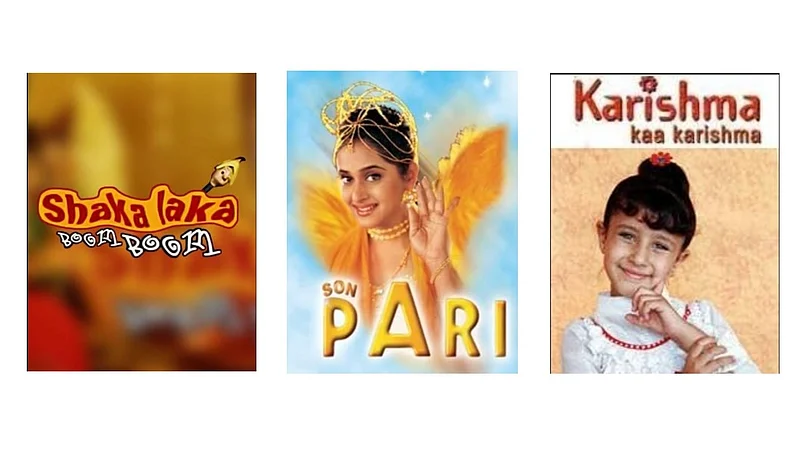

Growing up, films like Makdee (2002), Koi Mil Gaya (2003), and Taare Zameen Par (2007) left lasting impressions. “More than films, television shaped us," he recalls. "Son Pari (2000-2004), Shaka Laka Boom Boom (2002-2004), Karishma Ka Karishma (2003-2004). We also relied heavily on dubbed content. Harry Potter on Pogo was bigger than anything else." The last children's film that stayed with him was Avinash Arun's Killa (2014). "It's sad," he says, "but very few children's films get made today."

From his perspective, the issue is not creative trust but financial fear. "Writers might trust children as complex protagonists," he says. "I'm not sure producers do."

He believes children's films will return only when someone powerful decides to make one. "In the West, children's films are the biggest money-makers," he says. "Here, we're waiting for one success to change the conversation."

A Loss, Not of Nostalgia, but Attention

The disappearance of children's films is not just about missing a genre. It reflects a broader cultural shift. Cinema no longer pauses for the child's gaze. Children are absorbed into family audiences or outsourced to screens. Their inner lives remain unexplored. As Gulzar once said, children are silent and disenfranchised.

Perhaps the question is not where children's films went, but why. Perhaps they never truly arrived. Perhaps they were always provisional, allowed briefly before being replaced by louder, safer stories. But children are still watching. Still forming memories. Still searching. As Desai puts it, "They'll appear again if we see a demand for them. It's as simple as that." The real question is whether Hindi cinema is willing to see children not as future adults, but as people right now.