Summary of this article

2016 was not defined by one kind of film. The range made the year stand out.

It was a moment when Hindi cinema was willing to argue with institutions, with power, and sometimes with itself.

Hindi cinema can still tell brave stories, but the question is whether it can do so openly, without retreating into silence, spectacle, or safety.

Lately, the idea that 2026 is the new 2016 has taken the internet by storm. Comparisons abound, from fashion to pop culture, but nowhere does the nostalgia feel as charged as in Hindi cinema. 2016 wasn’t a golden age. It had blind spots, compromises and plenty of safe, formulaic films. Yet a decade on, as the industry becomes murkier and more risk-averse, it’s hard not to look back at that year with a pang of longing.

What people seem to miss isn’t just a slate of strong films, but a moment when Hindi cinema felt willing to argue with institutions, with power, and sometimes with itself. Comparing 2016 to 2025 reveals more than shifts in platforms or aesthetics; it exposes how the space for dissent, complexity and creative risk has steadily narrowed under censorship pressures, market consolidation and the rise of streaming.

2016: A Year That Refused to Be Singular

2016 was not defined by one kind of film—that range is precisely what made the year stand out. Big-ticket star vehicles like Sultan, Dangal, MS Dhoni: The Untold Story, and Airlift dominated the box office, but they were not hollow spectacles. These films engaged with ideas of masculinity, nationalism, discipline and redemption, often reinforcing mainstream values while still allowing room for complexity.

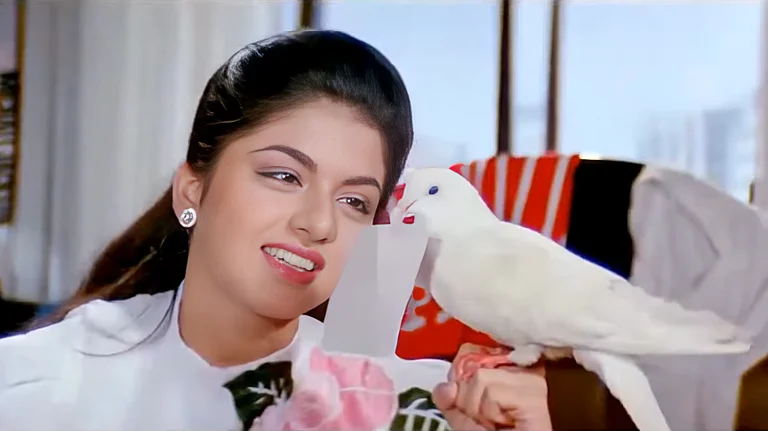

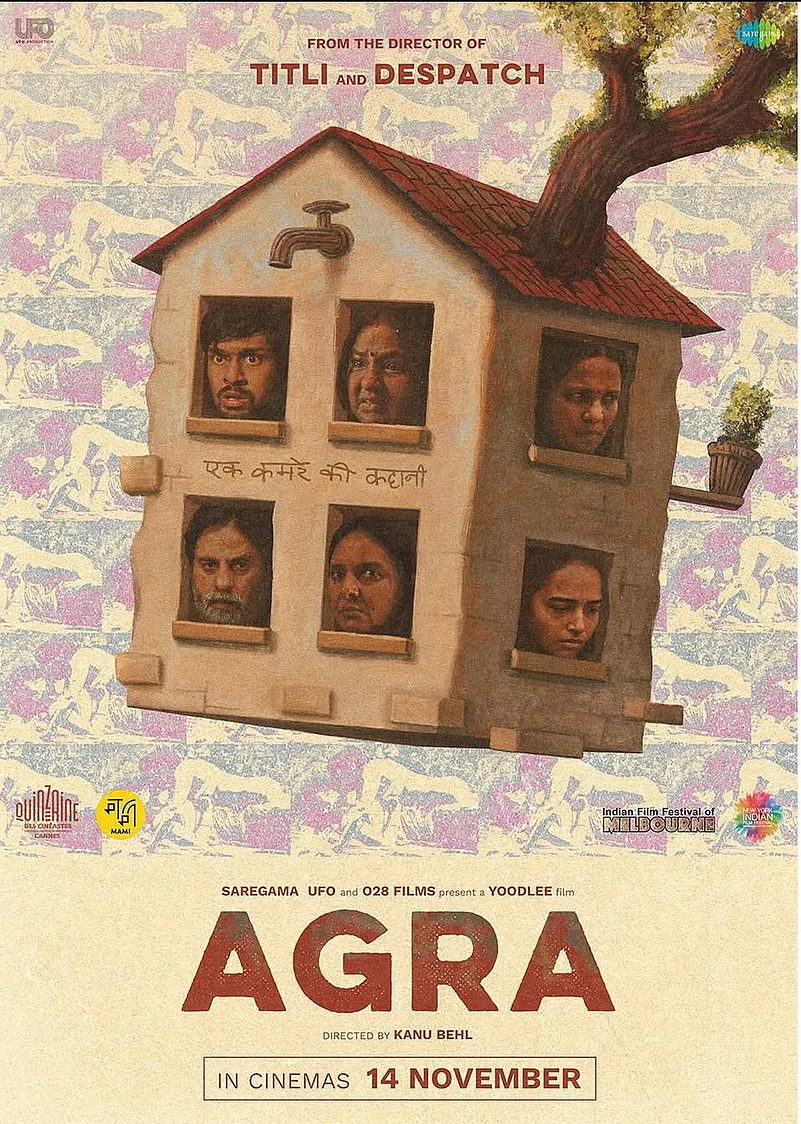

At the same time, Hindi cinema’s riskier impulses found space in the mainstream. Udta Punjab confronted state complicity in Punjab’s drug crisis with unusual directness. Aligarh centred the quiet dignity of a gay professor, refusing sensationalism. Pink reframed consent through a courtroom drama that spoke clearly to contemporary misogyny. Neerja portrayed female heroism without exaggeration, while Kapoor & Sons brought queerness and generational conflict into a star-backed family drama.

Alongside these, films like Raman Raghav 2.0 and Fan pushed formal and psychological boundaries, even when it came at the cost of commercial comfort. What linked these films was not a shared ideology, but a sense of confidence. Hindi cinema seemed secure enough to hold contradictions at once—to be commercial and confrontational.

The Shock of Udta Punjab and the Possibility of Resistance

The controversy around Udta Punjab is important because it showed a system that could still be questioned. Directed by Abhishek and starring Shahid Kapoor, Alia Bhatt, Kareena Kapoor Khan, and Diljit Dosanjh, the film faced multiple cuts from the CBFC ahead of its release. Its makers challenged these decisions in court and eventually received relief from the Bombay High Court. The episode played out through official orders, media coverage and public discussion, reinforcing the idea that censorship was something filmmakers could push back against rather than quietly accept.

Contrast this with today, where a film like Punjab ’95, directed by Honey Trehan and starring Diljit Dosanjh, has remained unreleased for over two years, caught in a cycle of negotiations, objections and delays. The uncertainty surrounding its fate speaks volumes. The confrontation has shifted from public to procedural, from open resistance to quiet erosion.

From Confronting Power to Performing Safety

In 2016, Hindi cinema often felt willing to confront power directly. Films like Udta Punjab exposed systemic failures, Aligarh quietly revealed social prejudice and Pink challenged entrenched ideas about consent. These films did not merely gesture at social realities; they named them. The controversies that followed, particularly censorship battles and public debates, reinforced the sense that filmmakers could still argue with institutions openly. Even when obstacles arose, they were contested and sometimes resolved through courts or public pressure. The resistance was visible.

That same year also marked the arrival of Netflix and Amazon Prime Video in India—platforms that seemed to promise an escape from theatrical constraints. Streaming was imagined as a space where stories deemed too political, risky, or niche for theatres might finally breathe. While original Indian content did not arrive immediately, early series like Inside Edge (2017) and Sacred Games (2018) reinforced the belief that long-form storytelling on OTT could explore crime, politics, caste and institutional decay with the freedom mainstream Hindi cinema was beginning to lose.

For a brief period, this promise felt real. OTT series, in particular, appeared to offer greater narrative space and thematic ambition. Yet, as streaming platforms expanded in scale and influence, they absorbed the same logic of caution that governs theatrical filmmaking. What was once imagined as a refuge for unfiltered expression became another ecosystem shaped by brand safety, audience management and an aversion to anything remotely political. Writers and showrunners have since spoken about increasing constraints on storytelling, marking a clear shift from the early years when OTT was associated with experimentation and creative risk.

Today, censorship rarely announces itself solely through the CBFC. It operates upstream, at the stages of writing, pitching and commissioning. Stories are softened, edited, or abandoned before production begins, shaped by an awareness of backlash, deplatforming, or professional consequences. What has changed is not just where control is exercised, but how quietly it functions. Hindi cinema has moved from confronting power to performing safety, whether in theatres or on streaming platforms. Boundaries are no longer crossed because they are often never approached.

The Death of the Mid‑Budget Film

Perhaps the most tangible loss over the decade is the disappearance of the mid‑budget, idea‑driven theatrical film. In 2016, Aligarh received a theatrical release despite its limited commercial prospects—an acknowledgment that some stories deserved public space regardless of box‑office fate. Back then, mid‑budget films could still find room to exist in theatres, to be debated, and to reach audiences outside festivals or streaming platforms.

A decade on, the scenario has shifted dramatically. Films like Agra struggle even to secure a theatrical release, often caught in controversy long before audiences can see them.

Mid‑budget films are increasingly viewed as commercial liabilities. They are risky propositions that neither promise box‑office returns nor align with the spectacle‑driven priorities of today’s multiplex programming. As a result, many such films are fast‑tracked to OTT platforms in their first window, where a digital release is framed as a privilege rather than the baseline expectation. A case in point is Mrs. (2025), directed by Gautham Menon and starring Sanya Malhotra. Despite its nuanced engagement with emotional and social pressures and a strong central performance, the film never reached theatres. It was released directly on ZEE5. In an earlier moment, a film like this might at least have had a limited theatrical run, allowing audiences to encounter it collectively and in public. Today, such films are positioned as digital-first not by creative choice, but by platform economics and risk management.

Streaming platforms may offer these films visibility, but they also reveal a deeper structural shift. Mid-budget cinema, once the space where commercial appeal met artistic risk, is now largely confined to subscription libraries. Theatres are reserved for star-led spectacles and franchises, while idea-driven films quietly slip into digital catalogs. This is more than a change in distribution. It marks a shrinking of cinema’s public life, where fewer films are seen together, argued over, or experienced beyond algorithms and login screens.

Risk Relocated: Daring Cinema at the Margins

Risk in Hindi cinema hasn’t vanished; it has relocated. It now lives either at the margins, in festival circuits, limited releases, or on streaming platforms, or is inflated into a large-scale spectacle where political and social questions are often diluted by size. The middle ground, where mid-budget ideas once met mass audiences, has largely eroded.

Two films from 2025 illustrate this shift. Sabar Bonda (The Cactus Pear), directed by debutant Rohan Kanawade, was the first Marathi film to premiere at Sundance, winning the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic. Despite international acclaim, it has struggled for visibility in India, with no OTT release and access largely limited to festivals.

Similarly, Humans in the Loop, directed by Aranya Sahay, earned critical praise for its nuanced exploration of labour, technology, and empathy. The film qualified for Best Original Screenplay at the 98th Academy Awards, though it was not shortlisted or nominated. After a limited theatrical run in India, it reached a broader audience on Netflix, highlighting how risk-driven films navigate uneven paths between festivals, digital platforms, and theatres.

These cases are not failures of ambition or craft, but reflections of an industry where risk-taking has been pushed to the margins, celebrated in global circuits and embraced by critics, yet struggling to find space in commercial theatres or comfortable digital windows at home. What survives today is not a disappearance of daring but its relocation, to festivals, to niche platforms, and to audiences willing to seek it out rather than encounter it collectively.

Sanitisation as the New Normal

Neeraj Ghaywan’s Homebound (2025) was one of the most critically discussed Hindi films last year, earning recognition on the international circuit at festivals like Cannes and TIFF. Its festival journey was widely celebrated, and the film later became India’s official entry for Best International Feature at the Academy Awards, even making the shortlist in that category, a rare achievement for a contemporary Hindi film.

For its domestic release, the version shown in Indian theatres underwent multiple CBFC-recommended cuts. According to industry sources, around 11 edits shortened the film by roughly 77 seconds, trimming scenes of discrimination, muting certain words, and reducing a cricket match sequence, resulting in a U/A 16+ rating.

What is unsettling about this discrepancy is not just the fact of the cuts, but the contrast they foreground: the version that travelled and earned acclaim internationally was shaped differently, collectively understood as the film, while the version Indian audiences saw was altered to conform to domestic sensibilities. Where once scenes were debated publicly, today such modification happens quietly and without visible resistance.

This dynamic reflects how sanitisation has become normalised. Where interventions might once have sparked public debate or legal challenge, as in the case of Udta Punjab, now restraint is accepted without fanfare, even when it affects material central to a film’s thematic thrust. The discomfort that once made cinema a forum for discussion is gone. Homebound’s journey from festival acclaim to a trimmed domestic release makes this clear: creative negotiation often happens before audiences see the film and rarely faces scrutiny.

The Return of Loud Nationalism, Without the Argument

If political dissent has grown quieter in Hindi cinema, nationalism has done the opposite. Films in 2025, like Chhaava and Dhurandhar, embrace chest-thumping narratives that leave little room for questioning. In 2016, even patriotic stories often carried ambiguity or inner conflict. Airlift framed evacuation as logistical heroism rather than military bravado. Today, the tone is more straightforward, more about affirmation than inquiry.

What stands out about this wave is not just how loud it is, but how safe. These films rarely challenge the state or complicate power. Nationalism is packaged as spectacle: emotionally stirring, morally simple and commercially secure. In a climate where dissent can bring scrutiny, such films act as a kind of protective shield, politically legible, easy to sell and largely immune to censorship.

The difference from 2016 is striking. Udta Punjab directly called out the state machinery and faced consequences for it. A decade on, cinema seems more comfortable celebrating power than examining it. Nationalism has become a signal rather than a conversation. The bigger loss is not ideology, but imagination—when affirmation replaces questioning, narrative depth suffers.

Looking Back, Looking Forward

Looking back at 2016 isn’t about nostalgia; it’s about measuring how much space for risk has narrowed. Hindi cinema can still tell brave stories, but the question is whether it can do so openly, without retreating into silence, spectacle, or safety.

If 2016 was a year when filmmakers felt they could speak back to power, 2026 shows an industry negotiating just how quietly it must speak to survive. The future depends on whether silence is seen as stability or recognised as the cost of caution.