In this exclusive interview, Hidayat Hussain Khan talks about his upcoming album 24,000 Miles.

The importance of adaptability in the new age of music and collaboration with Western musical artists, such as Jay-Z.

The power of music to connect the audience and performers, and why it is important in today’s political climate.

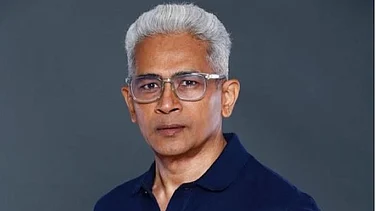

In the age of a fast-paced world, sitarist and vocalist Hidayat Hussain Khan reflects on what continues to keep Indian classical music relevant. The son of the legendary Ustad Vilayat Khan, globally acclaimed as one of the greatest sitarists of all time, Hidayat Hussain Khan possesses a rare, creative brilliance that transcends all genres of music. He has performed at The Black Ball Charity in NYC with Alicia Keys and has collaborated with a wide range of artists across genres, including Yo-Yo Ma, Jay-Z, Ndugu Chancler, Ronnie Wood, Ustad Zakir Hussain, Pete Townshend, and Will.I.Am.

In a candid conversation with Rani Jana for Outlook at the Mahindra Kabira Festival, Hidayat Hussain Khan talked about the new age of music, collaboration with Western artists, the importance of art and music in contemporary times of rising religious tensions and his upcoming album 24,000 Miles.

In today’s times, when everyone is watching 60-second reels, your performance needs immersion, time and patience. How do you feel your art stays relevant in this era of quick, fast entertainment?

I think there is a time and place for everything, and in the right time and place, everything is appreciated. A raag doesn’t have to be 45 minutes long to make an impact.

We are at the Mahindra Kabira Festival, which makes so much sense because he wrote dohes (couplets), right? In two lines, what he said hasn’t even been written in books.

So, I don’t think the importance is whether it’s 60 seconds or 45 minutes. It’s about the content. What is your intention and what is the content that you are trying to present?

In today’s world, with rising religious tensions, how do you think music and art make an impact?

Every art form is a statement because every painting tells a story, every piece of music tells a story. I’ve been lucky to be happy in my skin and be able to say what I want to say through my music. It only makes an impact on people who have that sensibility. Sometimes it connects, sometimes it doesn’t, and I know a few people connect with it, and I’m happy with that.

You have said that beauty in creative arts often lies in imperfection, in the raw, unscripted moment. What do you have to say about the current era of music, which is dominated by autotune and post-production polish?

I don’t necessarily think there’s anything wrong with autotune or BPM—they are tools. When technology is used to enhance what you’re saying, it’s beautiful. But when technology becomes the main subject, it becomes mechanical. Personally, I feel the most beautiful portraits of people have slight imperfections—a crooked smile, for instance. That’s what makes them beautiful. I feel the same about music. We aren’t perfect ourselves. Folk music is deeply imperfect, but the passion in the storytelling takes over and perfection doesn’t matter. There’s a fine line. You need to embrace technology, but music also needs to be real. Reality takes time. As creative people, life experiences shape how we communicate. Music is communication—it’s the BPM of your heart. When the energy rises, the rhythm rises; when it relaxes, it settles. That’s real communication.

You once mentioned that music creates a space where everyone breathes the same feeling. What are you describing when you say this, and is it specific to Indian classical music?

When I play the sitar, no words or visuals are telling you what I’m communicating. I’m watching your expressions and having a conversation with you. Then you land on a note thinking of love, inspiration, or spirituality and you see the audience in the same place as you. That’s the magic of music. With Indian classical music, especially in intimate settings, I can engage with each person. Artists like my father (Vilayat Khan) could grasp 10–20 thousand people and bring them into sync—their heartbeats, breathing, energy. I’ve experienced the same thing in smaller, more intimate spaces. That’s what I mean by breathing the same feeling.

Do you think digital platforms can recreate that shared presence, or is something lost outside a live room?

Digital convenience is incredible, even though we complain about it. Every era changes and we have to adapt. Older generations often project their fears onto younger ones, but the younger generation navigates digital spaces seamlessly. The pendulum always swings. Politically, culturally, musically—it moves back and forth, but overall it progresses. We tend to romanticise the past, but every ‘time’ had its difficulties. Today, music is accessible instantly, and that’s okay. The energy of earlier decades won’t return and that’s fine too.

You come from a seven-generation lineage and speak of rediscovering your father’s compositions rather than inheriting them. What changes when you return to Ustad Vilayat Khan’s music?

Great work always has more layers than we can understand at one moment. As we grow, we rediscover it. My father always said that what he taught wasn’t etched in stone—it was an idea. My mother helped create a clear distinction between entitlement and tradition. You walk into a music room not just as yourself, but as part of a lineage. Once you balance that, you keep learning.

You’ve collaborated across genres and cultures from Yo-Yo Ma to Jay-Z. How do you ensure fusion becomes dialogue rather than dilution?

Most musicians I collaborate with today have reached a point where they have some understanding of Indian classical music and its aesthetics. So I don’t really come across people who want to collaborate without that base. However, sometimes the final product does get diluted. For example, with the Jay-Z collaboration, I don’t even know where or how it was used, what was sampled and what wasn’t. The end product became very diluted. But the interaction itself was not like that at all. The interaction was actually a very good dialogue. It really depends on the senior person in the room at that moment. If I am the older one, then it becomes my responsibility to make you feel comfortable enough to speak in your own voice. And once you start speaking in your own voice, then it becomes a dialogue we are having. I’ve been very blessed that the senior musicians I’ve worked with have really enriched me and allowed me to say what I want to say, to be myself. And now that I’ve reached a certain age and place, when I interact with younger musicians, I try to create the same space for them. Then it becomes a dialogue.

What do musicians outside the Indian classical tradition misunderstand—or unexpectedly understand—about raag?

Raag is complex, not complicated. It has a technical structure, but beyond that, it’s a living personality. Like a person, it can express many emotions while still being itself.

If you lose that personality, you spoil the raag. Some people get too technical and lose emotion; others lose structure entirely. The balance of both is essential. Today, many musicians outside India understand this deeply, sometimes even better than I do.

Can you share a bit about your upcoming album?

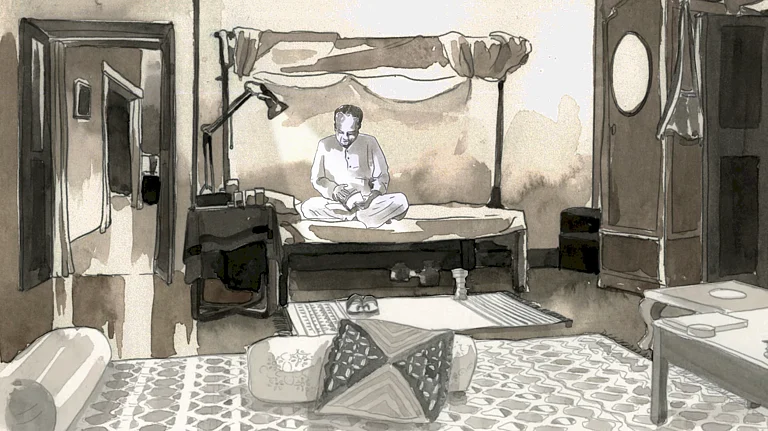

It’s called 24,000 Miles, which represents the globe. Each song is named after a city. It is cinematic, easy listening, loungy music, with Indian classical DNA beneath the surface. I want listeners to place themselves in the journey. So there’s a track called ‘Seville’, there’s ‘Mussoorie’, there’s ‘Lucknow’, and then there’s a second part to that, which is ‘New York’. Each of these songs has a story that I wrote before the music even happened. The stories are imperfect because I wrote them myself, but that imperfection reflects who I am. When you read the story and then listen to the song, it becomes very cinematic. It is about movement, migration, chaos, and peace, much like life.

We are in Varanasi for the Mahindra Kabira Festival. Will there be a song about the city in your new album?

Yes, it is a part of 24,000 Miles Volume II. Kashi is such a chaotic place. In one square block, a funeral pyre is burning, someone is taking a dip in the Ganga, someone is dancing, someone is praying, someone is just sitting there, someone is dumping garbage. There is so much chaos, but there is also so much peace. I am an atheist, so to speak; I don’t believe in man-made religion. The whole business of temples, rituals, money—honestly, it irritates me. But even within that, something else exists.

When I visited the Kaal Bhairav temple, it struck me that despite the chaos of queuing up to see the deity, all of us were breathing the same energy. It becomes a collective feeling. You have people coming from completely different walks of life—someone comes to Kashi with deep religious faith, someone else comes with none at all. Someone believes in Shiva, someone doesn’t believe in anything. But at the end of the day, everyone feels the same peace. That shared energy doesn’t ask where you’re coming from or what you believe in. It just exists.