Summary of this article

Sarmad Sultan Khoosat's Lali marks the first all-Pakistani production at the Berlinale.

The film circles a marriage jostling under social imperatives as desire takes defiant root.

Ahead of the world premiere, Khoosat sat down for an exclusive interview with Outlook.

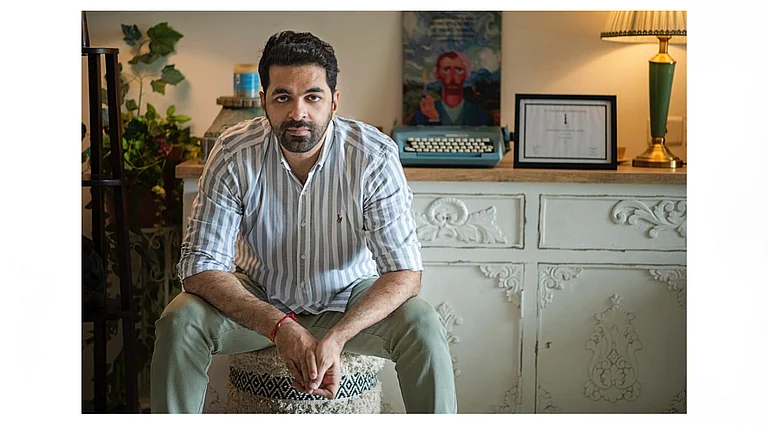

Pre-eminent Pakistani filmmaker Sarmad Sultan Khoosat brings his latest, Lali, to the Berlin Film Festival, slated in the Panorama section. Dashing between the uncanny and erotic, this portrait of newly weds Zeba and Sajawal gets your pulse racing, whilst abruptly sparking a cold sweat.

As Pakistan’s first all-local production at the Berlinale, Lali is richly rooted, peculiar and vibrantly startling. Khoosat fashions a volatile tonal temper, swerving from intensely taut atmosphere to awkward, imploding admissions. Desire is the fulcrum, trapped in crosshairs of customs, conventions and social institutions. Zeba and Sajawal’s marriage is edged with danger projected as predestined. Zeba’s past three suitors had dropped dead. What’s tossed as a curse has come home to roost, standing in for codes of masculinity the husband is haunted by. Generational trauma thrusts in between. With a sharp eye for the miasma, the ghosts settling in socially bound relationships, Khoosat mixes dread and desire in a heady, lush concoction. As the couple on the perch, bristling at social assumptions versus their own insistent impulses, the leads, Mamya Shajaffar and Channan Hanif, seize your attention with deeply embedded, swinging psychological nuance.

Ahead of the world premiere, Sarmad Sultan Khoosat opened up in an exclusive conversation with Outlook’s Debanjan Dhar, where he touched on the need for the film’s tonal shifts, sex in its myriad loaded avatars and crafting an alternative personality for his mother, whom he considers his primary audience. Edited excerpts:

Let’s begin with the impetus—the little paragraph from your aunt’s short story that sparked it all stuck with you for years. Why did you keep going back to it and expand it?

I do feel there’s a strong connection between literature and film. It’s an easy resource to go back to whenever you’re feeling brain dead or creatively infertile. Growing up, I didn’t watch a lot of films. Visuals weren’t my thing. Stories always attracted me. I like to believe I’m an avid reader. Yet, the postcolonial influence was such that we either read mostly English literature or translated stuff from all over the world. Short stories and fiction have a rich tradition in Urdu. However, I was mostly under the rock and had only flashes of it. My exposure to it widened only after my foray into television. Then I thought there is a dearth of contemporary fiction in English. Then this co-actor aunt of mine told me she had some semi-published stuff that she’d read out in literary circles or ladies’ clubs. She had a personality that already felt right out of a Victorian novel. Those stories were scandalising. They talked about eye-opening themes in a very real colloquium. It was also in line with my interest in Manto. They spoke about desire, the sensory. I thought then I could never adapt them for TV, given their highly sensual texture. But at the core, as I grew older, they came from keen observations of an experience I wouldn’t have a window to otherwise.

One particular story, Kaala Kambal, fascinated me a lot. When you grow older, there’s recollection and nostalgia. Broadly, the story was talking about marriage—how it’s an overly important thing in the subcontinent. Somehow, the dots kept connecting. This last paragraph in the six-page short story, which is what we kept, bloomed into something different. I’m so happy because there are many ideas you’re keen on breathing into and they die out. I’ve always been obsessed with the story of Charulata, wondering how you could adapt it without looking too much like a fan of Tagore or Ray. That this idea did actualise is a relief.

I wonder about the relationship between time and storytelling, particularly knowing when you’re ready to tell which story. How has the passage of years accented and shifted the way you perceive the story, the implications it contains?

Absolutely. As you grow older, your perspective on everything changes. That’s the beauty of creative expression. It’s so alive. If you’re truly connected, it helps you grow with it. I do feel I’m drawn to a slightly formal, older world. I like picking something which is a bit distant, which helps me create more around it. I’m pretty flexible with the source material. It’s a catalyst of sorts.

Without spoiling, there’s this incredible arresting, dramatic, absurd opening. How vital is it for you to take off on a strong foot? Do you fixate on the opening scene while writing and then proceed?

The alchemy of process is strange. I do like clarity. I cannot be haphazard. I do give myself enough time journalling, saving things on my phone, doing voice memos. It’s a lot of clutter. However, once I sit to write, my first step is to collect it all. Strangely, with this film, that originating paragraph from the short story became the third act. That story is much plainer in tone. It reads like a family drama. The way I read it was more restrictive. Here, the big unlocking was ‘I need to go dark comedy on this’. Having seen quite some stuff from the recent world cinema scene, it gave me courage to toy with the blend of genres. The film, I’d like to believe, is definitely grounded in the Punjabi culture but has a dark comic punch to it.

We have to talk about Sohni ammi—such a barnstorming character who just immediately takes us captive. Was she the most fun to write?

I think it’d require therapy sessions (laughs). It’s such a futile attempt to hide yourself from your creative expression. I’m obsessed with my mother. She’s long gone, but the idea of her, the life dished out to her, is a mix of fond, sweet, sour and painful. Layer by layer, I keep bringing some of her to most of my stories. Sohni ammi isn’t exactly like my mother. I wish my mother were like her. It’s almost like writing an alternative personality for my mother. In the short story, the mother was a side character. Here, I wanted to flesh her out more before the seeming protagonists of the film. Sohni ammi is how I feel a lot of Indian and Pakistani moms should be, with that fire, fearlessness, zest and passion to live. She does have scars and stories but turns them into everyday banter. It was super fun co-developing her then with the actress playing her (Farazeh Syed).

The film digs deep into anxieties around masculinity, the trauma that often triggers its own loop of further violence. In the beginning, it’s Zeba though who’s the one taking initiative. Sajawal is repeatedly referred to as someone who keeps hiding. Talk about etching that graph of intimacy with Mamya and Channan, going between the erotic and unnerving…

To begin with, the institution of marriage is so celebrated, even in pop culture that trumpets the suhaagraat. You jostle with these conforming ideas that you’ve grown up with, around marriage, masculinity, fidelity and modesty. I’d never read Albert Camus. But when I read The Outsider, the idea of grieving through sex rose. If you throw these words together in our society, they’d come at you with daggers (laughs). People use marriage to make sexual behaviour kosher or acceptable. It’s also weaponised as the biggest tool of abuse, not always bordering on marital rape but as transactional behaviour. I wanted to thread it as a cause-and-effect thing, but it didn’t fit. It’s such a carnal, basic human need that people meander through it with unsureness. That’s what helped me post the big plot point when we enter the strangely dark but borderline comic idea of consummation. In our local dialect, the reception event joke is the marriage would be valid only if it is consummated. This thread continues and from there we go to the deeper, complex trauma of Sajawal, who has lived under the shadow of an alpha mother. He sees Zeba too is alpha but he likes it and is excited on a physical level, but the psychological scar left by Sohni ammi remains. It was tough preparing the actors for such beats. We managed to explore all shades. Sexual behaviour can be an expression of anger, grief, basic desire, or trauma being unleashed on another person. At the same time, it can also be a sweet romance.

What drew you to Channan? Is this his first acting role?

Pretty much. He’s done some roles in the UK. I worked with him when he was really young. His mum and I did a stage play where he played our son.

I am curious about your own consciousness as a filmmaker when you’re pitching something for a global audience. Tell me about walking around in that space, preserving local textures, cadences, the music being so key…

It has become a conundrum. You’ve to reverse engineer a lot. It does become a burden. It seems unfair—the western lens is limiting. Do I need an essay to go with my film? It’s a precarious path to walk. I’d keep the global audience as my secondary audience. Wherever stories originate, they need to be authentic and primarily communicate to that audience. When you have dialogues, rituals, costumes, everyday habits, you cannot be footnoting everything. The core of what we are talking about is biological, a psychological conflict, broad ideas around union, family, obsessing over living together. I’ve never taken my films to labs. I’m so drained by the writing process, the pre-production. It might get contaminated if I took the lab route. But this is an admission of a skill I don’t possess.

The Berlinale acceptance comforted me. Filmmakers are expecting a pressure to make it global first. I don’t want to take that right away. Of course, while developing, you do tweak here and there if you’re being too culturally specific. Like in the film, I can give the example of the jamun denoting the color purple and purple belonging to the family of red which runs throughout the film. Even the subtitle says java plum, which is weird (laughs).

It feels there’s a spike in western interest in works from Pakistan. Over the last few years, there have been Kamli (2022), Joyland (2022), Barzakh (2024) at Series Mania, In Flames (2023), Karmash (2025) breaking out. But you have spoken about working in a languishing film industry. In such a climate, how do you find artistic solace and kinship, the conviction and faith to go on?

It has to take some insanity to make films, to be honest. You create something with your heart and hand it over to so many collaborators—the DP, the production designer, the actors, etc. It’s such a constant battle of where you’ve to be a tyrant or democratic and all-encompassing. However, the new wave is shaping in Pakistan. The number may be small, but there are people who’ve given me solace that we can do it together. When I make films, I don’t go to my TV lot where veterans are there. I like working with younger filmmakers, where ideas are fresh and the ethos is vibrant. The solace comes from having found some people with whom I love making films. Also, there is an audience that engages and appreciates the work. I’ve never made money with my films. For that, I do my TV stints and commercials. That’s why there’s the space between one film and the next.