Summary of this article

Lali marks the first all-Pakistani feature at the Berlin Film Festival.

Directed by Sarmad Khoosat, it's a darkly comic psychological drama opening with a marriage and laced with equal parts seduction and danger.

Lali premiered in the festival's Panorama sidebar.

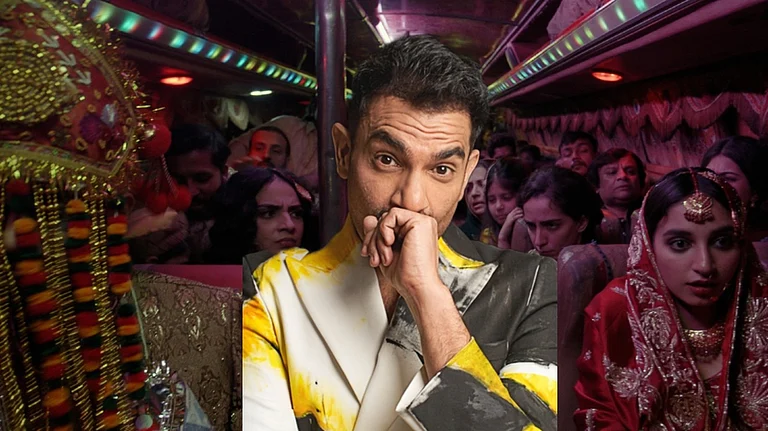

A marriage is laid bare in Sarmad Sultan Khoosat’s arresting new film, Lali. The new bride, Zeba (Mamya Shajaffar), carries a reputation smeared by rumour. Her past three suitors had dropped dead. However, her husband, Sajawal (Channan Hanif), insists himself he’ll outlive the superstition's reach. He vows to dispel the touted curse. But there are other phantoms to face—bones rattling in the closet. How long can they be tucked away?

Premiering at the Berlinale in the Panorama section, notably Pakistan’s first all-local production at the festival, Lali segues between the mundane and the uncanny, rising above a single, defined tonal throughline. With costumes by Ayesha Imran and Zoya Hassan to die for, this will easily endure as one of the year’s most exquisite films to behold and awe at. Sarmad moulds a hotbed where colliding, fiery emotions cohere into a peculiar, craggy beast of its own. Deferred intimacy between the couple shifts uncomfortably within a strange, teetering psychological reckoning. Desire, combustible and insistent, flares in the air. Its heat buzzes like a subterranean whisper, a persistent thought urging consideration. The couple is poised in a place of uncertainty, see-sawing between leaning into it and recoiling. Should they embrace the impulse or step back?

Consummation is anticipated but scars of both impinge. The marriage weathers immense, grinding social prescriptions. They must first confront and exorcise their individual demons. Each has secrets and wounds, guilt and shame. Danger has marked out the relationship from the very start. Superstition and hearsay lace Zeba’s entry into the household. It’s lodged into her existence itself. Sajawal’s sister (Mehr Bano) is suspicious and cold to her. The minute something awry happens, she doesn’t waste a moment to pin all blame on Zeba.

Sajawal is reserved and retreating. His sister calls him out for hiding and disappearing on every important occasion, absent even on their father’s funeral. Hanif sharply captures the fibre of a deeply haunted man, the sore gaps between trauma, the yearning looking for tenderness. There are emotional bruises and unspoken misgivings going back to his childhood. The scarlet scar on his face is also emblematic of masculinity he’s supposed to project. Neither have the old taunts and hounding left. Under the thumb of his domineering mother, Sohni ammi (Farazeh Syed), those gashes were never discussed, let alone redressed. Rather, they have stuck on, lingering for triggers such as the arrival of Zeba who bears echoes of Sohni ammi’s spirit. The zesty mother is one of those life-affirming characters that instantly annexes our hearts. Syed runs away with every scene she’s in, almost daring us to try looking away and fail. Sohni ammi has endured a lot, but refuses to let that reduce her appetite for life. Syed and Shajaffar share one of the film’s best scenes as one shares with the other the brutal blows life has dealt.

Bordered by social mores, how does love and desire unleash itself? Can marriage sustain its restrictive parameters? Initially, Zeba is assertive and demonstrative, putting Sajawal at unease. She’s not coy but advances without hesitation. In a superbly orchestrated first half, Khoosat stages their post-marriage courtship, failed stabs at intimacy with a tinge of comic absurdity. There’s delicious skewering of the apparatus and fuss around wedding rituals, peaking in the couple’s first night. He’s allergic to flowers, so she hastens to adjust the rose-twined bed, which only collapses in the scramble.

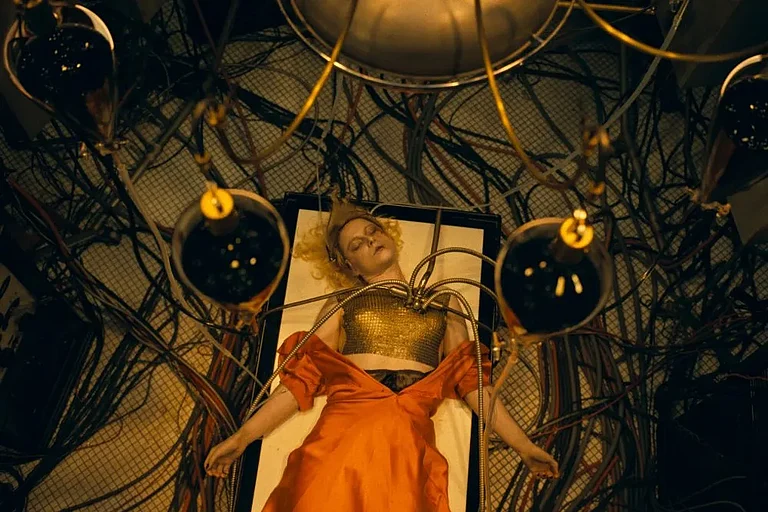

Unembarrassed about bold, vivid splashes of colour, Khoosat is a visually luxuriating filmmaker. Here, he also cements his status as the most stunning sensualist. The luscious colours on screen, rendered in Khizer Idrees’ camerawork, pop, simmer and drench the way we absorb the characters and unwieldy dynamics. So does the rich music, serving as key to transitions and disruptions in a sad, moody, sexy and atmospheric saga. Scenes are designed to hang off a precipice, making us skate between anticipation and dread. Khoosat also folds in surreal crossfades, transposing stylised dramatisation of the dead. The dunes cradle the women’s recollections in the film.

Shajaffar and Hanif thrum up a fearless, visceral chemistry. They dive into the tale’s thrusting erotic fervour, teasing and tantalising. Both bring a scorching intensity that’s impossible to shake off. A film like this demands actors to be locked into the tiniest flash, the most fleeting tremor. Saim Sadiq’s edit precisely hones in on dramatic oscillations—that low hum of disquiet that slowly accrues to a climactic eruption. Sexual envy props up as Sajawal’s insecurities escalate. The house appears to fade and decay, choked under a jealous man controlling his wife. The camera drifts through Zeba’s emotional and physical isolation. The air thickens. Life is leached out of her. She catches her breath, he scanning each move and following her gaze.

Admittedly, the screenplay, which Khoosat co-wrote with Sundus Hashmi, does have some flab. Around the midway point, the film runs in circles, retreading core ideas around patriarchal anxiety and distrust, though Shajaffar and Hanif invest every beat with tension and volatility. When the story threatens to be shaky, pay attention to Kanwal Khoosat’s meticulous, lived-in production design. Her work evokes the very heartbeat of a house shutting itself in. Zeba’s neighbour, Bholi (Rasti Farooq, a piercing presence), quietly observes it all and becomes her strongest ally. Lali veers between a cloistering psychological drama and a twisted absurd farce careening off the rails. Thankfully, Khoosat maintains a deft hand on a tricky tonal tightrope, held in no small measure by his fully committed actors. Equally assured and fluid is how the filmmaker unravels intimacy and its myriad faces. Violence seems tipped to consume everyone. There’s an entire gamut Lali crosses with glory and daring.