Summary of this article

Shoojit Sircar and Vikramaditya Motwane come on board to present Varun Tandon’s globally acclaimed short film Thursday Special. The film released on January 29 on the Humans of Cinema YouTube channel.

Thursday Special tenderly follows Ram and Shakuntala, a couple bound by love, routine and their shared passion for food.

In this interview with Sakshi Salil Chavan, Varun Tandon reflects on his filmmaking journey and his endeavour of bringing this film to life.

Varun Tandon’s latest short film Thursday Special (2026), backed by Vikramaditya Motwane and Shoojit Sircar, premiered on Humans of Cinema’s YouTube channel on January 29. Since its release, the film has steadily reached audiences across rural, urban and even international contexts. Amid this reception, it becomes important to examine what truly goes into the making of a thirty-minute film and the many years of labour invested in shaping it.

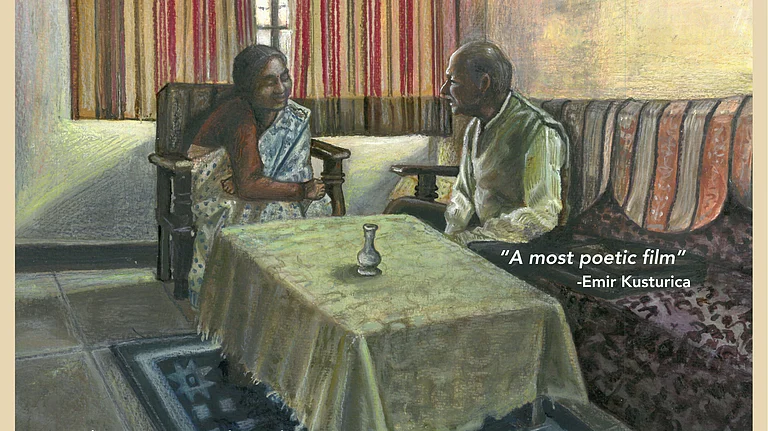

Thursday Special is a delicate sustained companionship and embracing change, anchored in the quiet ritual of food shared by an elderly couple played by Anubha Fatehpuria and Ramakanth Dayama. The film had already built a strong international reputation before its public release, premiering at Mecal Pro in Barcelona and winning over twenty five awards, including Best Narrative Short at the New York Indian Film Festival and the Tryon International Film Festival in the US. Positioned within this landscape, Thursday Special becomes not only a moving cinematic work but also a case study in how contemporary short films survive, travel and create meaning beyond production.

In this conversation with Sakshi Salil Chavan for Outlook, Varun Tandon reflects on his journey across writing, editing and direction. He also unpacks his Mumbai experience, the practical realities of shooting, the politics of indie cinema distribution and his upcoming creative pursuits. Edited excerpts:

Thursday Special has travelled through festivals and reached a wide audience. After living with the film for a while and watching people respond to it, what has surprised you most about how Ram and Shakuntala’s story is being received?

Since the film travelled and had screenings outside India as well, the reception has been deeply encouraging. Although each screening develops its own set of responses, which has been fascinating to observe. At the Mumbai screening, for instance, audiences laughed and found certain bits funny. At other screenings, people seemed to want to laugh but were uncertain whether they should, so they held back a little. Then there were screenings that rendered audiences visibly emotional, such as the one we experienced in Germany. While writing, my co-writer and I tried to remain honest with the material. We never forced the narrative to behave in a predetermined way or decided that a scene had to land in a specific manner. Instead, we wrote what felt organic in the moment and remained open to the idea that the film would be received differently across contexts and cultures.

What truly surprised us after the release on YouTube was the volume of messages from viewers who watched the film with their families, especially with their mothers. We had not anticipated that response and it has been deeply moving. Today, there are very few films one can comfortably sit and watch with one’s family, particularly with one’s mother. Even audiences from smaller towns are resonating with the film and continue to leave thoughtful comments and messages. The reach has therefore become far more accessible than we had initially imagined. In many ways, these are outcomes one cannot fully predict while making a film about family dynamics, including how, where and with whom it will ultimately find its emotional connection.

Do awards and festival recognition help you trust your instincts more or do they make you more aware of audience expectations when you approach a new story?

No, actually it is the opposite for me and I will try to answer that honestly. For instance, my last film Syaahi (2016) won a National Award just one month after it was made and it left a very strong impact. Yet, I realised that instead of making me chase recognition, it made me more focused and more rigorous about doing something right. You cannot think about festivals while making a film and you cannot even think about the audience, because once those become priorities, the story stops being the centre. The moment you start thinking about those outcomes, your vision can become corrupted and less pure. The priority must remain the film itself and the story you want to tell—told in the way you believe in and executed to the best of your capability.

After that, whatever happens, whether in festivals or with audiences, is not in your control. That is why I genuinely try not to think about them at all. Awards may offer reassurance; but if tomorrow, you make something equally honest and it does not receive the recognition, which is beyond your control, it should not crush you either. One has to learn that discipline. It is almost like classical music, where the practice and integrity of the form matter much more than external applause.

Both Shoojit Sircar and Vikramaditya Motwane came on board after watching your film. What was that journey like, from pitching Thursday Special to hearing that they wanted to attach their names to it?

I always treat festivals as a platform to get a head start once a film is made. However, our ultimate goal was always to ensure that the maximum number of people actually watch the film. Many filmmakers are often unable to distribute their work because there is limited access and the films end up remaining only on their computers. I keep telling them that they must release their work in some form. So, our primary aim was to take the film to as many people as possible. Then we realised that it would be meaningful to have storytellers we deeply admire present the film.

Me and Krati had been working towards this for the last five or six months, thinking carefully about how the film should be released. Shoojit Sircar and Vikramaditya Motwane were people we really respect because of their consistent support of independent cinema and we felt they would be ideal collaborators in this process. Both of them ended up loving the film. The process required patience and time but their response was generous and sincere. Once they agreed, the logistics and formalities unfolded quite smoothly. Releasing it on YouTube, thus, for us, became the most meaningful way to bring the film to audiences.

In Thursday Special, so much rests on the faces, chemistry and silences between Ram and Shakuntala. How did you approach casting these parts and how did you know they were the right match?

Casting, in fact, proved to be a difficult and time-consuming process. It took us a while because we had a very specific visual and emotional sensibility in mind and that extended to the actors as well. For the role of Ram, Ramakant ji was suggested by our casting director Aamna Mishra. Once we saw his appearance and his overall presence, he immediately felt right—both in terms of look and the energy he carried. We then sent him the script, which he responded to very warmly and the process unfolded organically from there.

Finding the actor for Shakuntala, however, was far more challenging. For a long time, we simply could not find someone who fit the part and eventually I reached a point of near surrender. At that stage, I contacted Sarika Singh, who had acted in my earlier short film Syaahi and comes from a theatre background. I shared the script with her and after reading it she suggested Anubha ji. She read the script and immediately connected with the emotional and conceptual space we were trying to build.

Because the pandemic interfered, our rehearsals were conducted remotely. We never rehearsed together in-person before the shoot. Instead, we worked through multiple Zoom sessions, focusing less on blocking and more on tone, atmosphere and the inner world of the characters. By the time we arrived on set, both actors intuitively grasped what the film required and execution became much more fluid. We spent time visualising the film and shaping the production design so the house felt lived in, not staged. This coherence between space, tone and performance helped the actors understand the vision and inhabit it fully.

In the film, the city of Kannauj itself seemed to become part of your set. You’ve mentioned using stand-up, songs and storytelling to keep the crowd engaged so the shoot could continue. What did that experience teach you about control versus surrender while making a film in a living, breathing space?

Yes, it was genuinely challenging. When you visualise something for months or years and finally get only one day to execute it, the pressure is immense. If it does not work, it feels deeply discouraging. Beyond technique, the real challenge is confronting the unpredictability of the real world, where crowds, light and movement cannot be fully controlled, yet time keeps pressing you forward. Because of these constraints, we could not afford many takes. On the streets we barely managed two or three, so preparation with the actors became crucial. We had to stay fast on our feet and trust the process. Shooting in public spaces made me realise how much production support such scenes truly require.

Even without dialogue, managing people and space is demanding, especially when a camera like the Alexa Mini instantly attracts attention and gathers crowds. We often worked within five-minute windows before people began reacting or speaking. My father assisted with local production by distracting the crowd with jokes so we could shoot quickly. At one point, my sister even wore a sari and sunglasses and posed as an actress to divert attention, which helped draw people away. These situations are not taught in film school. You learn them only through practice. My main takeaway was that one must be relentless with oneself. You cannot give up. You have to push through uncertainty to make the work possible.

Your short film Gulcharrey (2016) felt particularly intimate. It reminded me of Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine As Light (2024), where Mumbai is portrayed as a city full of love but with little tolerance for its expression. How has your own relationship with Mumbai evolved through your years of living and filming here?

It is a difficult question and one I am still thinking through. I came to Mumbai for college after growing up in a boarding school and living here felt entirely new at first. Everything was unfamiliar yet exciting. After college, when I entered the industry as a freelancer, the city became more demanding and at times lost the romanticised vision of it I carried during my student years. The practical realities of sustaining oneself professionally can change how you see the city.

Over time, however, I have come to truly love Mumbai. Among all the places I have been, it is perhaps the only city that lets you be. It is difficult to explain to someone who has never lived here, but that openness feels unique to Mumbai. The city is also where I found my filmmaking family. My cinematographer, production designer and editor are the same people I worked with when I was eighteen, on my first film that cost around three hundred rupees. Today, we are all working professionally and still creating together. People respond when they see passion and honesty in your work. For instance, Motwane sir and Sircar sir connected with the film’s energy and supported us. Once you bring sincerity to the table and keep doing the work, support eventually follows.

In your award-winning short Syaahi, Himanshu Bhandari, who played young Vansh, was a non-actor. Working with children brings its own rewards and challenges. What were some of yours in that film?

It was an immensely rewarding experience. When I first met Himanshu, he possessed an almost magical quality in the way he expressed himself. It is a rare talent. I genuinely enjoyed working with him. While working with children, I realised that many adults tend to underestimate them, not necessarily by looking down on them but by assuming a certain limitation in their understanding. I actually believe that children are, in many ways, more intelligent and sharper than us because their thinking is direct and unfiltered. You do not speak down to them. You speak to them as equals.

In that sense, I became very good friends with him. We spoke often and developed a space of equality where he could trust me. I consciously tried to create that environment for him and for the other child actor as well. Because of that, their performances emerged naturally. I also deeply enjoy working with non-actors, even in smaller roles, like in Thursday Special because they bring an authenticity to the texture of the film that trained performers sometimes cannot replicate. It adds a lived-in quality to the narrative. However, working with children is also challenging during a shoot. You never know when they will offer a magical moment and when they might lose interest, so you must stay on your toes. Overall, I truly enjoyed working with children in Syaahi, and I believe that experience translated meaningfully into the film’s emotional fabric.

Many people talk about falling in love with cinema later in life, but you were drawn to storytelling from childhood. Do you see your films as a dialogue with your inner child?

Before I am a filmmaker, I am also an audience. When you ask where the most exciting ideas come from and why a particular thought emerges, for me they arise from what I most want to watch. You think of a story and suddenly realise, “this is a film I want to experience.” Naturally, that generates excitement and activates something childlike within you. The excitement must remain childlike because filmmaking is a long and demanding journey. Without that sense of emotional curiosity and personal interest, the process becomes exhausting. If you do not carry that initial spark of excitement with you, it becomes very difficult to stay invested in the work.

It’s often said a film is truly made on the editing table. As an editor yourself, does editing begin for you in pre-production? Do you think like an editor when you write? Has wearing both hats helped or complicated that process over time?

With regard to editing, I have edited commercially for other people, but I have never edited anything that I have written myself because I feel I need a different perspective. Otherwise, I become too close to the material. The editor, Amitesh Mukherjee has been part of my journey from the beginning. He edited the first film I made when I was eighteen and later edited this one with me as well. In that sense, we have grown up together, both professionally and as friends.

Because of this, I do think about editing even while writing. It happens instinctively. When you are visualising the film, you already sense how you are going to shoot it. So I think a great deal about editing in advance and the film itself is largely pre-planned. It is storyboarded or photoboarded and the visual language of the film is quite carefully designed. You imagine the cuts, the rhythm and the transitions while conceiving the film, but when you finally reach the edit, it becomes a completely different process. At that point, you forget many of the ideas you originally carried and begin to respond to what the material itself is asking for, its emotional logic, its limitations and its unexpected possibilities, rather than what you had imagined earlier while writing or shooting.

We have read that you are working on a feature for a prominent production house. Do short films still feel like your comfort zone or something you will keep returning to? What is your perspective on the state of viewership and distribution of indie short films?

For me everything begins with origin and impulse. My excitement comes from wanting to tell a particular story rather than choosing a medium first. I do not initially think in terms of format. For instance, even with Thursday Special, I first wrote it as a ten-page short story. Once the story exists, you begin to understand what the most appropriate medium is to communicate it. That material eventually became about twenty five pages and was translated into a short film. If it had expanded further, it could have moved towards a feature. I enjoy all formats, but the choice depends on what story feels urgent and exciting at that moment. At present, some ideas I am working on are still at an early writing stage but a few already demand longer forms, more time and space to explore their worlds and characters, so perhaps that is what comes for me next.

A lot of independent filmmakers in the industry desire a theatrical release, but today even an OTT release for independent film is very difficult. It was easier a few years ago. Now many films struggle to find distribution. It is a tough phase and all one can do is remain hopeful because ultimately people want their films to be seen. With short films, making the work is only part of the process. Filmmakers must also push it with the same seriousness. For me, sharing the film and receiving responses is the final step of filmmaking. After festivals begin, the responsibility does not end. If you are passionate, you will find ways to open the film up to audiences. Driven filmmakers often search for new venues and organise screenings because they care about the life of the film beyond production. Even if a short film releases online, it still needs to be actively pushed. The journey of Humans of the Loop (2024) was inspiring in this sense. The filmmaker Aranya Sahay travelled to film clubs, colleges and schools to keep the film alive. Especially for short films, it is the filmmaker’s responsibility not to abandon the work after it is finished but to guide how it meets its audience.