Doorva Bahuguna mentions that 92 per cent of women leaders across the world played some sport, which speaks of a lesson in beating all odds.

Instead of asking women to shrink their ambitions to fit unsafe environments, you fix the environments, says Bahuguna.

She further mentions that 'economics will follow the eyeballs, and the eyeballs will follow the quality of play'.

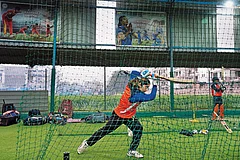

When Doorva Bahuguna played cricket in the late 1980s and ’90s, there was no money, little recognition, and no illusion that the sport could become a career. You played, she says, because something inside you demanded it. Today, women’s cricket in India has a league, salaries, sponsors, and visibility—but also new constraints, new narratives, and familiar battles over agency, safety and femininity.

In conversation with Lalita Iyer, Bahuguna—who captained Andhra Pradesh’s sub-junior, junior and senior cricket teams and later built a corporate career—speaks candidly about why grassroots matter more than pay parity, how sport reshapes women’s sense of self, and why the real revolution in women’s cricket is still unfinished.

How has public perception of women’s cricket changed since your playing days, and where do you think it still needs to evolve?

When I played, there was no money. No recognition. You played for the joy of it. Resources were barely there. We had crowd support if we played in university towns or local grounds, but otherwise, the stands were empty, even for international matches. And we didn’t win much as a country. It was never a career. It was something you did because something in you needed to do it.

Now it’s a legitimate sport. The Women’s Premier League (WPL) was a game changer. Money came in. The Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) giving equal pay was a brilliant move. For young girls today, cricket looks like an actual career option. Parents won’t have the same resistance to their daughters playing. That shift is massive.

What still needs to evolve is grassroots play. The talent pipeline has to grow for the game to move into a different league altogether. We need more girls picking up the bat at the age eight, not at 14. More school programmes, more district-level tournaments, more coaches who know how to spot and nurture talent early.

I’m not getting into the money debate. Yes, women still make a fraction of what men do outside of BCCI contracts. But frankly, I’m not very fussed about that. The economics will follow the eyeballs, and the eyeballs will follow the quality of play. Fix the pipeline, and everything else will sort itself out.

You’ve written about claiming space and power through sport. What do you think cricket teaches women about identity, strength, and agency?

You discover your body beyond how society and media describe it. You discover it has power, speed, and immense strength. You stop caring about the face you make when you hit the ball hard. Or how your butt looks when you run up to bowl a bouncer. You build a new identity—a strong, powerful woman who is not just breasts and lips. You rewrite what your body means to you. Not to society. That is a very different identity. You unlock mental reserves you didn’t know existed. It’s the mental callus you build from being told you shouldn’t be there, people mocking you. You play anyway. Because that’s what you do. That’s who you are.

And agency is the big one. In a world where women’s choices are constantly made for them, sport is one of the few spaces where the outcome is entirely yours. You could fail, but you fail on your own terms. That’s rare for women. And it carries forward into life.

You become less afraid, less conscious of yourself, definitely a better leader. Research shows that 92 per cent of women leaders across the world played some sport. Clearly, they are learning something that makes them beat all the odds.

Do you think media coverage of women’s cricket is finally catching up with the sport’s popularity? If not, what’s still missing?

Coverage has improved. The WPL got prime time slots. Major tournaments are broadcasted. Sports journalists are writing more thoughtful pieces.

But depth is still missing.

Men’s cricket gets analysis. Frame-by-frame breakdown of technique, debates about selection, entire shows dedicated to strategy. Women’s cricket still gets narratives. ‘She overcame poverty.’ ‘She defied her family.’ ‘She’s a role model for girls in her village.’ All true, all important. But also all-limiting.

Right now, the audience and media know the meta narratives. It is a great narrative, to be honest: Successful women in a sport adored by the country. In a sport which is still a man’s game. The story of women claiming space in it needs to be told first.

When audiences start watching keenly, deeply, the analysis will follow. You can’t have tactical breakdowns when people are still learning the players’ names. The depth will come once the breadth is established. We’re in the breadth phase. And that’s okay.

Safety and accessibility are often cited as major issues for female athletes—how do you balance protective policies with creating freedom and opportunity?

This is the question I wish more people asked.

Here’s the trap. Safety becomes an excuse to limit women. ‘It’s not safe for you to train late.’ ‘It’s not safe for you to travel alone.’ The intention might be protection. The outcome is restriction.

I wrote about this when the Tamil Nadu government introduced a chaperone rule for women athletes. Well-meaning, perhaps. But the framing was all wrong. You have to flip the responsibility. Instead of asking women to shrink their ambitions to fit unsafe environments, you fix the environments.

That means well-lit training facilities. Transport arranged by federations, not left to individual athletes. Hostels with proper security. Zero-tolerance policies for harassment that are actually enforced. Female coaches, physios and managers.

But here’s the thing. All risks cannot be eliminated. I have walked to bus stops at 4:30 am in the dark. I looked over my shoulder constantly. And I kept going. Sports gives you that confidence and that fearlessness. You learn to move through the world differently.

The balance isn’t about making sport 100 per cent safe. That’s impossible. The balance is about removing systemic barriers while respecting women’s agency to take calculated risks for things they love.

You’ve highlighted the idea that players sometimes must “perform femininity” to gain market appeal. How do you see that tension playing out in India today?

This isn’t just an Indian thing. Or a cricket thing. It is an industry thing.

Brands choose ambassadors based on ‘brand fit’. And brand fit, myopically, is decided by customer stereotypes. So if you want more endorsements, you have to make your visual and personality brand amenable to fitting more brands. This is sports—and gender-agnostic. Sad, but true.

Now, let me be fair. Charisma drives endorsements for men too. David Beckham’s smile sold Adidas and Pepsi as surely as his bendy kicks. Virat Kohli’s swagger multiplies his market value. M. S. Dhoni’s calm charisma and chiselled face make sponsors queue up. This isn’t unique to women.

But here’s the difference. The real tragedy isn’t that charisma and appearance matter in sport. They matter in almost all camera-facing professions. The tragedy is that women get punished for having the wrong kind of charisma while men are rewarded for any kind they bring.

If a woman doesn’t fit the typical feminine template, she gets called boyish. Man-ish (meaning like a man). I wish I could say ignored. But she is mostly mocked, mercilessly.

Deepti Sharma. Short hair. Power bowler’s build. Player of the Series in the World Cup. Irreplaceable winner in the team. But her ‘femininity performance’ is deemed sub-par. And so she hears things like ‘is that even a woman?’ And hardly gets any endorsements.

That’s the tension. And it’s not going away until brands decide they want to back athletes who look like athletes.

Looking back, which moment—on or off the pitch—do you feel summed up why you played?

I have many such instances. But let me recall the latest one.

Last year, I gifted my husband a half cricket pitch in our backyard. His male friends came over, playing tennis ball cricket. I was happily barbecuing for them and hanging with their spouses. Not really playing.

But then my husband called me over. I decided to hit a few balls.

And they were out of the park.

The look on the men’s and women’s faces when they saw me hit the ball that hard was totally worth it.

Girls can play. Girls can play well. Girls can play hard.

Every time I show this to people, gender-agnostic, it feels like I’m breaking notions. And every time I do it, I feel so good.

I guess this is why one played. To show that one can.

If you could implement one policy tomorrow to accelerate growth in women’s cricket, what would it be?

Mandatory women coaches at every level of the game.

Get retired players to train to become coaches. Build a female infrastructure for female sport.

Beyond representation, women coaches understand the specific challenges. The biology, most importantly. They’ve lived it. They know what young girls are navigating in ways that well-meaning male coaches simply don’t.

It will also give confidence to parents to send their kids. Knowing their daughters are being coached by women changes the conversation at home.

And it creates circular employment. Retired players don’t disappear from the ecosystem. They stay, they contribute, they shape the next generation. That’s how you build sustainable growth in women’s cricket.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

For young women who want to pursue sport as a career now, what advice would you give them—especially about resilience and identity?

Three things.

First, your body is yours. Not your family’s, not society’s, not the federation’s. Yours. What you do with it, how you train it, what you’re willing to sacrifice for it. Those are your decisions. Own them fully.

Second, build your identity on what you can control. You cannot control whether you get selected. You cannot control whether the media covers you. You cannot control whether sponsors come calling. But you can control how hard you work. You can control how you respond to failure. You can control whether you show up tomorrow. Anchor your sense of self to those things.

Third, find your people. Sports is lonely when you’re a teen. Your school friends might be doing sleepovers and fun evenings. You might miss out on that. And it’s okay. Make every minute on and off the court count, with the right people who get you and your life.

This article is part of the Magazine issue titled No More A Gentleman's Game dated February 11, 2026 which explores the rise of women's cricket in India, and the stories of numerous women who defeated all odds to make a mark in what has always been a man's ballgame.