Summary of this article

The arrests of Kartik Naik and Suneeta Pottam reveal how Adivasi leaders opposing mining, security camps, and land dispossession are criminalised through IPC charges, organisational bans, and stringent security laws like UAPA and CSPSA.

From colonial forest laws to contemporary development and conservation regimes, Adivasis have been systematically recast as ‘encroachers’ and ‘extremists’ for asserting constitutionally protected rights over land, forests, and self-governance.

Organisational bans and guilt-by-association allow the State to suppress democratic movements, enabling indefinite incarceration without proof of individual wrongdoing and turning political assertion into a punishable offence.

On September 19, 2024, Kartik Naik, a prominent leader of the Maa Mati Maali Surakhya Manch was arrested on multiple allegations under the Indian Penal Code (IPC), including of unlawful assembly, causing grievous hurt and attempt to murder. As part of the Manch, Naik had been organising Adivasis in several villages of Rayagada and Kalahandi districts of Odisha against a proposed bauxite mine by Vedanta which would subsume 1,549 hectares of land, including 699 hectares of pristine forests, in the Sijimali/Tijmali hills.

Earlier the same year, on June 3, 2024, Suneeta Pottam, Vice President of the Moolniwasi Bachao Manch (MBM), was arrested by the Bijapur police in Raipur without a warrant or informing her of the grounds of arrest. Since 2021, MBM had been organising against the establishment of security camps on customary lands without their free, prior and informed consent, human rights violations by security personnel, and the mass incarceration of Adivasis on allegations of extremism. As Pottam battled 12 criminal cases and got acquitted in nine, the Chhattisgarh government banned the MBM under the Chhattisgarh Special Public Safety Act (CSPSA) in October 2024 for creating public order disturbances and opposing state-led development works. In April 2025, she was re-arrested by the National Investigation Agency (NIA), this time under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), on allegations that the MBM was a front of a banned terrorist organisation. Pottam remains in custody even today.

Elsewhere, in 2017, Stan Swamy and Xavier Soreng, Jesuit priests and social activists, approached the Jharkhand High Court seeking the release of undertrial prisoners languishing on allegations of ‘extremism’, as their trials remained pending for years in the absence of proper evidence, sanctions for prosecution, or charges. This Public Interest Litigation (PIL) emerged from a research report by Bagaicha, a centre for social action in Ranchi, which revealed a nexus between the dispossession of Adivasis from their lands and natural resources, and their systematic incarceration under security laws like the UAPA, Criminal Law (Amendment) Act 1908 (CLA) and others. Although Stan Swamy was soon arrested on similar allegations in the infamous Bhima-Koregaon case, where he died in judicial custody, the PIL remains pending for nearly a decade.

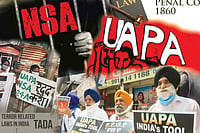

When we think of ‘political prisoners’, we usually imagine an individual targeted by the State under so-called ‘false cases’ for their advocacy of socio-political causes. We speak of such persecution as perversions of the law, as a ‘misuse’ of State power against innocent persons or those exercising ‘legitimate’ dissent. But in limiting our gaze thus, we miss the systematic creation of Adivasis as criminal subjects in the colonial and postcolonial State project of resource appropriation—whether as ‘encroachers’ on their own lands, or ‘extremists’ exercising their livelihoods and political freedoms. The legal framework of persecution in these three episodes invite us to view the incarceration of individuals as an exercise in collective punishment against democratic movements and marginalised groups asserting their political freedoms and statutory rights. In this matrix, security legislations like UAPA, CSPSA, CLA, as well as the IPC (now Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita or BNS) provisions relating to unlawful assembly or conspiracy anchor themselves in the criminalisation of association first, which then extend their tentacles into the wider socio-economic and political lives of Adivasis in central-eastern India.

The colonial government appropriated land, forests and natural resources through a series of legislations in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century encoding the doctrine of eminent domain. For instance, the Indian Forest Act 1927 (IFA), which continues to operate today, met this goal through bureaucratic and criminal mechanisms by vesting the right to govern forests in the State. On the other side, existing rights of Adivasis and other forest-dwellers were extinguished and forest-based livelihoods criminalised, turning them into encroachers on their own lands.

The same architecture of eminent domain in laws like the IFA, Land Acquisition Acts etc. have been used, and even expanded upon, to fuel the development aspirations of the independent Indian State over the past seven decades. It is no secret that Adivasis have borne the brunt of development through mass internal displacement and dispossession to pave the way for large dams, industries and natural resource extraction.

The Constitution of India, under the Fifth Schedule, recognises the rights of Adivasis to their customary land and forests, prohibits the alienation of such lands, and empowers traditional institutions like gram sabhas with decision-making authority. The Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act 1996 (PESA) mandates prior consultation with gram sabhas for the use of customary lands, forests and natural resources for development projects. The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act 2006 (FRA), in a further leap, attempts to undo the historical injustice by which forest-dwellers were made encroachers on their own lands by recognising individual and collective tenure over forests, and recognising the right of gram sabhas to protect and manage their customary resources. In the Niyamgiri judgement of 2013, the Supreme Court held that this included the right to free, prior and informed consent for the diversion of customary forests for any non-forest purposes. This decision has been affirmed multiple times thereafter by other constitutional courts, and by the Supreme Court as recently as December 2024 in a matter concerning protection of sacred groves in Rajasthan.

Despite these protective constitutional and statutory provisions, the language of ‘encroachers’ persists, and is now deployed in ever-evolving contexts, of conservation and securitisation. In February 2019, the Supreme Court issued an eviction order against ‘encroachers’ of forest lands in a PIL filed by retired forest bureaucrats and ‘conservation’ NGOs challenging the constitutionality of the FRA. Mercifully, the order was put on hold, but evictions of so-called ‘encroachers’ in the name of conservations continues, as reflected in the struggle of the van gujjars of Corbett and Rajaji National Parks in Uttarakhand.

It is not simply that Adivasis have been dispossessed as ‘encroachers’ or as collateral damage of India’s development aspirations. Historically, the exercise of their constitutional and statutory rights to customary land and forests has been criminalised and subject to brutal police violence. Recall the police firings that killed eight Munda Adivasis in the struggle against the Koel-Karo hydroelectric project in Jharkhand in 2001; the Kalinganagar police firing of 2006, which killed 13 people, including three women and a minor, for protesting against the Tata steel project in Jajpur, Odisha; or the police firing of 2021 in Silger, Chhattisgarh, where four Adivasis were killed, including a woman, for opposing security camps on customary lands without the gram sabha’s consent. The Silger police firing became the trigger for the birth of the MBM.

In 2017, much after all 12 villages had unanimously rejected bauxite mining in Niyamgiri on the strength of the 2013 verdict of the Supreme Court, the Niyamgiri Suraksha Samiti (NSS) was targeted under the UAPA for being a ‘front’ of a banned terrorist organisation in an attempt to re-open the question. The Pathalgarhi movement in Khunti and surrounding districts of Jharkhand in 2018, which opposed the creation of ‘land banks’ and dilution of protective legislations, too resulted in sedition FIRs against more than 10,000 persons, including Stan Swamy.

The arrest of Kartik Naik in Tijmali falls in the same lineage. A year prior to his arrest witnessed a spate of illegal detentions, followed by arrests of prominent anti-displacement activists in August 2023, on the eve of public hearings as part of the EIA proceedings for the proposed bauxite mine. In December of the same year, the government conducted statutory consent proceedings with the gram sabhas, which the affected villages later challenged before the Odisha High Court as being ‘fake’. January 2025 witnessed further disruptions of public assemblies in affected villages and FIRs against scores of unnamed persons. Despite these violations of the right to free, prior and informed consent, the bauxite mine recently received Stage-I forest clearance under the Forest Conservation Act (now Van Sanrakshan Evam Samvardhan Adhiniyam).

By all accounts, this regime of dispossession and criminalisation is set to exacerbate in the coming years. Since the COVID-19 pandemic (and earlier), the central government has overhauled the legal framework governing forests, environmental protection and mining in the interest of ‘ease of doing business.’ This overhaul opens the floodgates for privatisation of forests, provides exemptions from legal compliance for an expanding list of projects, dilutes consent requirements and environmental safeguards. In late 2025, the Chhattisgarh High Court added another nail in the coffin of forest rights through an unprecedented order upholding the cancellation of collective titles granted to gram sabhas. This cancellation has cleared a central legal hurdle that had plagued Adani’s coal mining project in Hasdeo for a decade.

It is in this landscape of dispossession and criminalisation that security legislations like the UAPA, CSPSA, CLA and others operate. Usually, laws like UAPA become the focus of civil society approbation for their ‘misuse’ against individual political prisoners, who languish in jail under indefinite pre-trial incarceration on account of the statutory prohibition on bail. Certainly, this is a matter of concern.

However, the heart of such security legislations lies in the power to ban organisations. Under UAPA, organisations may be banned as ‘unlawful’ under Section 3, or as ‘terrorist’ under Section 35. While the ban of an unlawful association is valid for a period of five years and follows a pretense of procedure before an ad hoc Tribunal comprising a sitting judge of the High Court, bans on terrorist organisations operate permanently, and are not afforded even a pretense of prior review. CSPSA, too, encodes the power to ban an ‘unlawful organisation’ for a period of one year, following a post facto review by an Advisory Board which may or may not comprise a judicial officer.

Beyond issues of vague definitions and arbitrary action, organisational bans enable the State to expand the net of criminalisation through the logic of guilt by association. The State does not need to prove individual instances of wrongdoing, but can bring an infinite number of persons into indefinite and punitive pre-trial detention on the simple allegation that the accused is a member of a banned organisation. In Pottam’s case, this logic goes further, to allege that the accused is a member of another organisation, which is itself not banned, but is simply declared in an FIR or chargesheet, as a ‘front’ of another banned organisation. Although the ban on MBM under CSPSA has now lapsed, Pottam continues to be in custody on allegations that MBM is a front of a terrorist organisation. The Chhattisgarh government, in its notification under CSPSA, had not made any allegation of MBM being a frontal organisation.

As the 2016 Bagaicha report points out, this phenomenon of an ever-expanding net of criminalisation on the logic of guilt by association is not simply about ‘false cases’ or ‘misuse’ of the law. Thousands of Adivasis are incarcerated on low-threshold allegations of membership following persistent violations of arrest procedures and a schematic scarcity of evidence. The Supreme Court had an opportunity to ameliorate, if not rectify, this state of affairs by upholding the standard of ‘active membership’ under Section 10 of the UAPA, which would require active complicity in acts of violence or unlawful activities. In its Arup Bhuyan-II decision of 2023, the Supreme Court rejected this proposition and endorsed criminalisation based on mere allegations of membership.

These so-called ‘encroachers’ or ‘extremist’ prisoners may or may not be ‘political prisoners’ of our imagination who are targeted for their advocacy of socio-political causes, but are the systematic creation of criminal and security legislations that view Adivasis as a whole as an inherently suspect class of criminals and terrorists.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Radhika Chitkara is assistant professor (law), National Law School Of India University, Bengaluru

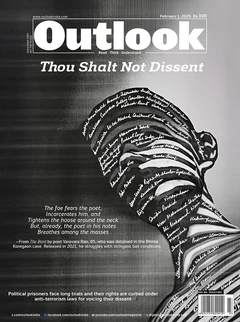

This article is part of the Magazine issue titled Thou Shalt Not Dissent dated February 1, 2026, on political prisoners facing long trials and the curbing of their rights under anti-terrorism laws for voicing their dissent.