Earlier, you could be living in Nehru Nagar, going to school via Gandhi Marg, and having ice cream at Indira Chowk. You would likely go for higher education to Kamala Nehru College, Jawaharlal Nehru University, or Rajiv Gandhi University — or a place named similarly.

You can still do all of this but now you can also watch a cricket match at Narendra Modi Stadium, board a train from Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Junction, study at Atal Bihari Vajpayee School of Management and Entrepreneurship, become a security researcher at Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, and train to be a diplomat at Sushma Swaraj Institute of Foreign Service.

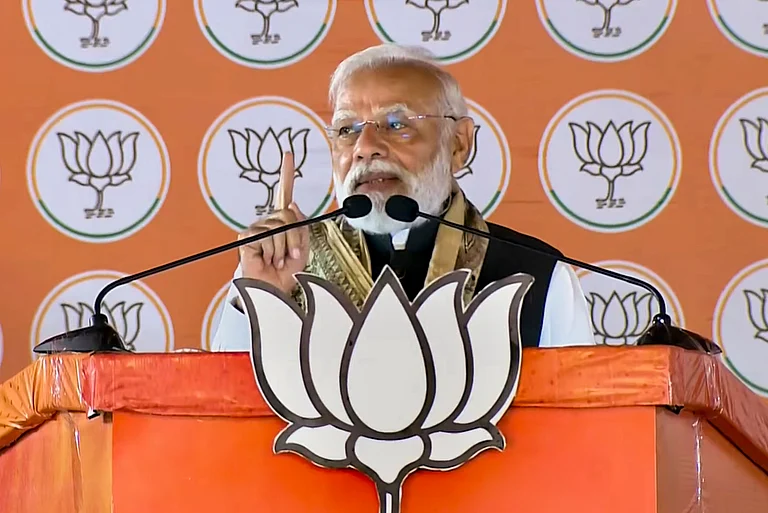

While the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led governments have changed names of urban spaces and cities, they have also indulged in assigning names to places. In doing so, the BJP has pushed for its own pantheon of icons in the public sphere which was hitherto the domain of its bete noire Congress.

The push of the BJP for its own set of icons over those of the ancien regime of the Congress comes at a time when Prime Minister Narendra Modi is talking of a “New India” and his critics are accusing him of eroding the idea of India. It also comes amid contrasting visions of not just India’s present and future but also of the past, with Modi’s BJP facing frequent criticism for painting history in one shade.

The BJP’s push for own icons

In 2018, the Narendra Modi government changed the name of the Mughalsarai Junction in Uttar Pradesh to Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Junction. The station has long been the railway hub connecting Western and Eastern India.

The erstwhile Mughalsarai Junction is located along the historic Grand Trunk Road (GT Road) that has connected Kolkata to Peshawar in Pakistan for the past 2,500 years, according to UNESCO. Incidentally, Sher Shah Suri, the mediaeval Indian ruler who famously revamped the GT Road, was also purged from the University of Delhi’s undergraduate history syllabus roughly around the same time.

Pt. Deen Dayal Upadhyaya —a leader of Jana Sangh, predecessor of BJP— is not the only one who has been ushered into the mainstream consciousness under Modi’s stewardship. There are others too who were otherwise well-known but were relatively out of public space.

Such icons who have now entered the public space include the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) ideologue Syama Prasad Mookerjee, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Arun Jaitley, Manohar Parrikar, and Sushma Swaraj, among others.

In October 2019, the Chenani Nashri Tunnel in Jammu and Kashmir was renamed as Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Tunnel. The renaming was done within weeks of scrapping J&K’s special status and downgrading it to a Union Territory (UT) from a full-fledged state on August 5, 2019. The message was not lost on anyone. Mookerjee died in Srinagar under arrest in 1953 at the orders of the then J&K ruler Sheikh Abdullah. When his son and grandson were in detention in 2019, the BJP government renamed a key roadway after Mookerjee.

However, the BJP faces one problem in this push for its icons. Its pantheon is not as large as that of the Congress. Unlike the Congress, the BJP does not have a line-up of freedom fighters. In such cases, the BJP has resorted to appropriation. It has already appropriated Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and is currently on its way to appropriate Subhash Chandra Bose. While Patel was honoured with the Statue of Unity in Gujarat, Bose was honoured with a statue near India Gate.

A contest for national imagination, place in history

The BJP’s push for its own icons comes at a time when there is a simultaneous push to reimagine the past where the Mughals as well as Delhi Sultanates struggle for a place. This manifests sometimes in syllabus revisions and sometimes in their deliberate absence from discourse on Indian history.

In a recent exhibition titled Glory of Medieval India: Manifestation of the unexplored Indian dynasties, 8th-18th Centuries, the Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR) featured around 50 dynasties but not a single Muslim dynasty.

Umesh Ashok Kadam, member secretary of the ICHR, told India Today, “Those people (Muslims) came from the Middle East and didn't have direct connect with Indian culture…Islam and Christianity came to India during the mediaeval period and uprooted civilisation and destroyed the knowledge system.”

Minister of State (Mos) for Education Rajkumar Ranjan Singh said there is a need to “refine” history.

While one understands the need for a nuanced conversation on mediaeval invaders, mediaeval sectarian confrontations, or temple-razing by the likes of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, the black and white perception of history where everything remotely Islamic in mediaeval India is to be shunned does not benefit anyone — except for those who want to erase that part of history instead of studying and talking about it with scholarly nuances.

Long traditions of changing names after icons

Though the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) since 2014 has advanced rather quickly with what it calls historical corrections by changing names of places and revisions textbooks and syllabi, the tradition was not at all started by the saffron party.

Ironically, the BJP is following in footsteps of its bete noir Congress. The grand old party has changed several names over the years — despite having no dearth of places named after its leaders, mostly from the Nehru-Gandhi family. For example, University of Delhi’s Hastinapur College —named after the ancient seat of Kuru clan, currently in Meerut district— was renamed as Motilal Nehru College after Pandit Motilal Nehru, one of the tallest Congress leaders of his time and the father of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. The Connaught Place was also named as Rajiv Chowk.

In Uttar Pradesh, Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) supremo Mayawati had renamed a number of cities after Dalit icons, such as Kasganj as Kanshiram Nagar, Hathras as Mahamaya Nagar, and Kanpur Dehat as Rambai Nagar. The decision was reversed by her successor Akhilesh Yadav of Samajwadi Party.