Over 22,000 Maharashtra schools are unsafe, and nearly 24,000 classrooms need urgent repairs.

Critics say the state is offloading its duties by asking alumni to fix crumbling infrastructure.

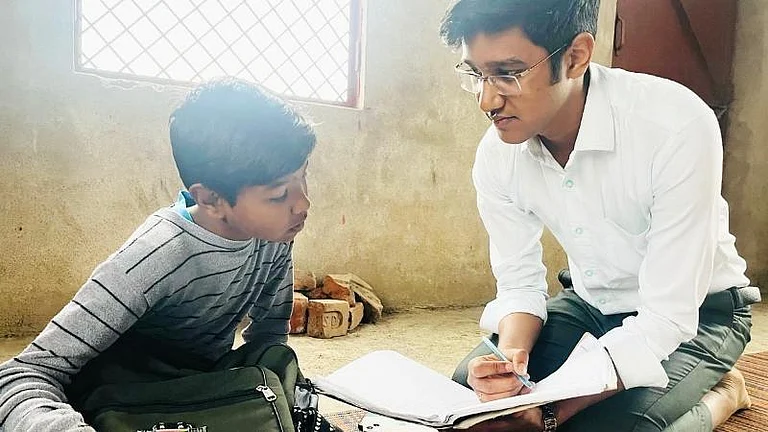

Despite flooded paths and collapsing roofs, students and teachers persist in their fight for education

In Bhim Dhanora village, students float across 40-feet-deep backwater lakes on slabs of thermocol, makeshift boats in the aftermath of the Marathwada floods that have swallowed roads across Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar. In another Maharashtra village, the entire safety of a school relies solely on a single wooden pole keeping the roof from collapsing onto the students

And in Nashik’s Vavi village, Vinod, a crippled boy of no more than ten years of age, trudges two kilometres of rocky, roadless terrain every morning just to reach school.

Across rural Maharashtra, children brave flooded paths, crumbling classrooms, and sheer neglect, driven by nothing more than their desire for an education.

What the Numbers Reveal

Recently, the Maharashtra government has asked all schools, including Zilla Parishad and municipal institutions, to form alumni associations to help upgrade infrastructure and student facilities. The October 1 government resolution says former students should assist with repairs, toilets, libraries, laboratories, and playgrounds.

While the move is framed as community participation, it effectively outsources the government’s duty to maintain public schools. In institutions already struggling with inadequate funding, critics question why alumni are being asked to shoulder responsibilities that should rest squarely with the state.

Educationist Mahendra Ganpule argued, “For many years, such alumni associations have been working in various schools. But for the government to come out with a GR in this regard means that it wants to throw off its financial responsibility and expect that the public and former students carry it.”

In March 2025, Maharashtra’s Minister of State for School Education, Pankaj Bhoyar, revealed that 22,716 zilla parishad schools across the state have been declared unsafe for years. Citing data from the Unified District Information System for Education (UDISE+) 2023-2024 report, he added that another 23,973 classrooms in 60,344 zilla parishad schools across Maharashtra require major repairs.

Enrollment in Government schools in the state stands at 60.9 per cent in 2024 for children aged 6-14, which is a sharp decrease from the 67.4 reported in 2022 in the Annual Status of Education Report (Rural) 2024 (ASER).

The ASER report underscored deep-rooted neglect in rural schools, revealing severe shortages of basic facilities such as drinking water, toilets—especially for girls—sports equipment, and libraries. In Maharashtra, the lack of safe drinking water and girls’ toilets remains particularly acute, reflecting persistent gaps in infrastructure.

A separate study by Child Rights and You (CRY) echoed these findings, highlighting widespread deficiencies across rural India: inadequate infrastructure, scarcity of essential learning resources like textbooks, teaching aids, and technology, a shortage of qualified teachers, and entrenched gender disparities that continue to limit girls’ access to education. The report also drew attention to the lack of proper transport facilities, which forces students to travel long, difficult distances simply to reach school.

But statistics only tell part of the story, failing to capture the everyday endurance of children who continue to show up, no matter the odds.

Maharashtra’s Mission for Education

Siddhesh Lokare, a social impact worker and influencer, set out on a mission to visit 30 schools across 30 districts of Maharashtra within 30 days to raise three crore rupees to provide underprivileged schools with basic amenities and decent infrastructure.

“The thing is that we are aware that problems do exist in rural schools; however, it is the extent of the problem that we are unaware of.”

Despite conducting surveys and research well in advance of their visits, Lokare and his team were shocked by the ground reality of local schools, which was far worse than they had anticipated.

“We found that the most basic amenities were almost completely missing in most of these schools. No water, no toilets, no desks or chairs for the students, and infrastructure on the verge of collapse,” he explained.

These realities don’t go unnoticed by the children. Lokare recalled an interaction with one of the young students: “I asked the boy if he could continue studying at his current school. At first, he didn’t say anything; perhaps his teacher had told him to stay quiet, but then he looked up at the roof.”

A single bamboo pole supported the roof of the school; any shift in pressure could bring the whole structure down on the students. “The boy finally said, ‘The school is going to collapse on us.’”

Lokare emphasises that accessibility remains one of the biggest issues affecting rural schools. “In our journey, we have come across children who literally trek for kilometres just to attend school.”

He explains that some of the schools he visited, despite lacking even the most basic amenities, have managed to achieve remarkable results in teaching their students. In one Marathwada village school, the children can write with both hands, solve complex mental math problems, learn about robotics, and even speak Japanese fluently.

“You can see in the documentation that these children talk about wanting to become IPS officers, going to college in the city or even playing in the Olympics — there’s a persistence in them to get an education and improve their circumstances,” Lokare says.

“There is change,” Lokare says, “but it depends on a handful of dedicated teachers who are willing to come to underprivileged schools every day and teach sincerely, and on NGOs that step in to support the financial aspects of maintaining and supplying these schools.”

Lokare looks ahead with optimism. “This journey and documentation have been only one part of our mission. Once the 30 days are over, we’ll return to furnish these schools and, hopefully, make the lives of these children a little better,” he says. By day 29 of the mission, they had already raised ₹2.2 crore.

Many NGOs that once partnered with these schools are now returning, drawn back by the social media momentum Lokare’s campaign has generated. While a few schools are beginning to see brighter days through such individual and community-led efforts, the Maharashtra government, too, has set its sights on systemic reform.

Education Minister Dadaji Bhuse recently announced that the teaching models of Vabalewadi School in Shirur and Jalindarnagar Zilla Parishad School in Khed — the latter which won the Community Choice Award in the World’s Best School Prizes 2025 by global organisation T4 Education — will be adopted across all Zilla Parishad schools in the state.

“The ‘students-teach-students’ model of Jalindarnagar Zilla Parishad School is revolutionary. With the combined efforts of teachers, students, and parents, the school has set an inspiring example not just for Maharashtra, but for the entire nation,” said Deputy Chief Minister Ajit Pawar.

As Bhuse put it, “When an entire village decides to develop its school, true transformation begins.” Despite this push, countless rural schools remain unseen, beyond the reach of social media or outside the radar of aid organisations. For many students, drifting to school on thermocol slabs or walking kilometres across rough terrain is not an exceptional case but a daily reality.