The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is celebrating 100 years of its unbroken journey.

No organisation can ensure its endurance unless it steadfastly remains connected with the people.

While the Left-Liberals used their power to create a legitimacy deficit around the RSS, the organisation, in turn, generated a credibility deficit for them through the ideological awakening of Hindus.

While the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is celebrating 100 years of its unbroken journey, its contemporary ideological movements—the Communists-Socialists and the Gandhian-Nehuruvian streams—are facing a crisis of existence. The RSS began in 1925 with a contested idea of a Hindu Rashtra. It lived and expanded in an unsympathetic political and intellectual climate. Many central services, including the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC), considered RSS connection as a disqualification. The newspapers and journals had given very little space in its favour. It did not have many intellectuals by its side. However, things progressively changed. The RSS emerged as the most influential organisation in the country with the largest network and support base. The Indian state is now in full solidarity with it. Prime Minister Narendra Modi released a commemorative stamp and coin to highlight its role in national life.

What is the key of the RSS’ success? The utility of this question is not confined to know about it, but has a wider ramification, particularly on our understanding of comparative perspectives of various ideological movements on vital issues like secularism, democracy and above all nationalism. The growth of the RSS resulted in marginalised ideologies of various shades opposed to it to get united under a loose banner of Left Liberals.

Unfortunately, unabated abhorrence for each other dominated the political scene and prevented engaging debates. Consequently, the Indian intellectual climate has been overshadowed by prejudices, polemics, and above all, pessimism.

The RSS lived with multiple perceptions. While predominant Marxist and Nehruvian intellectuals and political classes used propaganda and narratives since the late 1940s to create mistrust and misgivings about it among the people, the RSS simply ignored them and opted for grassroot activism, which required both patience and perseverance. It created a huge divergence in its works, as more than three dozen organisations are working in various fields. Common people found a vast difference between what the elite narrated and what they actually felt about the RSS. While the Left-Liberals used their power to create a legitimacy deficit around the RSS, the organisation, in turn, generated a credibility deficit for them through the ideological awakening of Hindus. Ideologies or movements that lack sincere and selfless groundwork are like forests without roots—and that is precisely what happened to the Left-Liberals.

No organisation can ensure its endurance unless it steadfastly remains connected with the people. Such an organic connection gives it the opportunity to understand their psychology.

The RSS deliberately avoided direct confrontation with them and allowed them to decay due to their own contradictions. Its approach echoed an Afghani proverb, ‘He who can be killed by sugar should not be killed by poison’.

Its founder Keshav Baliram Hedgewar dismissed compartmentalisation of ideologies believing that the evolution of an idea is a constant process—one that thrives only when an organisation shares its vision and engages in dialogue. He deeply understood the Indian psyche of collectivism and mutual dialogue.

Straightforward objectives, he understood, never attained transformation in either society or culture. The principle and practice of shared ideas, upheld as a cardinal principle, gave the RSS a distinct edge over other social and political movements. Moreover, the RSS consistently contextualised its ideas and consciously refreshed it.

No organisation can ensure its endurance unless it steadfastly remains connected with the people. Such an organic connection gives it the opportunity to understand their psychology. This, in turn, enables the organisation to reduce its idealism to practice. Historian Thomas Carlyle said that in reducing ideals to practice, the great latitude of tolerance requires not a lowering of standards, but rather a deeper understanding of human frailty. And RSS’ patience, tolerance and non-dogmatic attitude exhibited this wisdom, allowing it undivided and undiluted for over a century.

The shared ideas underlying the RSS programmes resemble, to an extent, ideas of the paradoxical forces—the Hindu Mahasabha, the Liberals and the Socialists. Hedgewar’s own idea of decolonisation brings French philosopher Frantz Fanon, the author of The Wretched of the Earth, closer to him. He pleaded in the Nagpur Court in 1921 for complete Independence and he, like Fanon, wanted to end it lock, stock and barrel. One can also find ideas of Ngu˜gu˜ wa Thiong’o, an African writer, resembling with that of Hedgewar’s. Both knew that more than political, cultural impacts destroy the originality of indigenous people.

It is the conviction in the shared ideas which led the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS) to play a leading role in the joint coordination committee of the trade unions, which include all the Left labour organisations. Karl Marx aptly said: “What is genuine is proved in the fire, what is false we shall not miss in our ranks.” Hedgewar’s nuanced approach of promoting shared ideas and inclusive programmes helped the organisation to receive support even from eminent individuals outside the Sangh. A large number of Congressmen, such as P. D. Tandon, K. M. Munshi, Sardar Patel, N. B. Khare, A. G. Kher, S. Radhakrishnan and Sampurnanand, mutually agreed and disagreed with the RSS on issues and ideologies. This became the reason for their marginalisation within the Congress, yet Hedgewar’s approach of social dialogue unfailingly continues without anyone’s ostracisation. Its stalwart, Dattopant Thengadi, enjoyed a great friendship with communist Bhupesh Gupta and other Socialist leaders. The RSS always attracted social progressives.

When Mahatma Gandhi visited an RSS camp in 1934 in Wardha, he found youth belonging to various castes like Mahar—the caste which B. R. Ambedkar belonged to and who were highly discriminated against—and Brahmins living, playing and dining together. Throughout their lifetime, neither Gandhi nor Ambedkar uttered or wrote a single word against the RSS. Both were outspoken advocates of social egalitarianism.

The files in the Prime Ministers Museum & Library in Teen Murti on the Congress reveal that many grassroot workers were issued show cause notices for their support to the Sangh. For instance, Narayan Prasad, a member of the Seoni district committee of the Congress in Madhya Pradesh, sent a letter to Seth Govind Das, the provincial head of the party, complaining that Rama Rao Upgade and Jatar, president and vice president of Seoni district council respectively, as well as the district Congress committee, supported the RSS and demanded action against them. The Tribune reported on December 14, 1947, that a prominent Congressman in Jalandhar, Chaudhari Lahiri Singh, addressed a rally of the RSS.

Similarly, in the K. M. Munshi papers, I found an interesting correspondence between Raj Kumar Mediratta and Munshi. Mediratta wrote to him on September 6, 1941, inviting him to join the RSS. The latter responded on September 13: “He knew the leaders of the RSS well, but he could not join the RSS.” Even Jayaprakash Narayan (JP), once a critic of the Sangh, got full cooperation from the RSS in the 1974 movement. But nobody in the RSS questioned or quoted JP’s earlier views, which harmed the organisation in public activism. Many socialists and Gandhians, including George Fernandes, Achyut Patwardhan, became comrade-in-arms of the RSS.

The RSS still has a long way to go to realise the goals of cultural nationalism and social and economic egalitarianism.

It is interesting that the organisation was formed on the day of Vijayadashami in 1925 and started activities on the Principle of Commune. After six months of rigorous discussions and voting by 25 founding members, the name of the organisation was decided. The commune continued to function, and only in November 1929, the position of the sarsanghachalak was created. The decision-making process in the RSS is based on multiple processes of extended deliberations where the feedback mechanism operates with remarkable effectiveness. In contrast, the principle of democratic centralism of the Communists and dynastic politics failed to refresh the leadership in their ranks. The RSS took an altogether different path of fostering collective will and collaborative functioning. It generated a dynamic power of enduring—a trait which it consistently demonstrated, both in favourable and challenging periods in its history.

Social progressivism is another aspect that creates a significant gap as to what critics say about the Sangh and how it is actually perceived by people. Sangh pracharaks travel divergent regions and places, yet they adapt the local cultures, languages, food habits and traditions, rather than imposing their own. This makes them more acceptable and adorable. An average pracharak knows many languages.

S. H. Deshpande, who was once associated with the RSS before leaving to become one of its most noted critics, shared his understanding and his reservation about the organisation in his article, My days in the RSS in The Quest, published from Pune in 1974. But even he agreed that the Sangh was absolutely free from narrow thinking or behaviour. “The RSS did leave certain imprints on my mind, which have not yet been erased. …the one achievement, which is, by far, the most significant from the point of view of national integration, is the sense of unity and brotherhood the RSS has been successful in creating in the minds of its adherents. True, this is confined to the Hindus, but the fact cannot be overlooked that in spite of its Maharashtrian percentage, the RSS is wholly devoid of any taint of chauvinistic Maharashtrian, which is decidedly a credit to this organisation. Invitations to its functions held in Maharashtra have always been printed in Hindi, a fact which underscores its opposition to parochialism.”

One of the biggest ironies in the discourse on Hindutva is that the critics of the RSS, including eminent historians—whether by design or unconsciously—treated the RSS as merely an acolyte of the Hindu Mahasabha, basing their criticism on the Mahasabha’s ideology, programmes and leadership. Hedgewar, in contrast, was a little-known nationalist who made a remarkable debut in the Gandhian non-cooperation movement in Nagpur. The Mahasabha, on the other hand, had a pan India presence with popular leaders such as V. D. Savarkar, B. S. Moonje, Bhai Parmanand and Shyama Prasad Mukherjee.

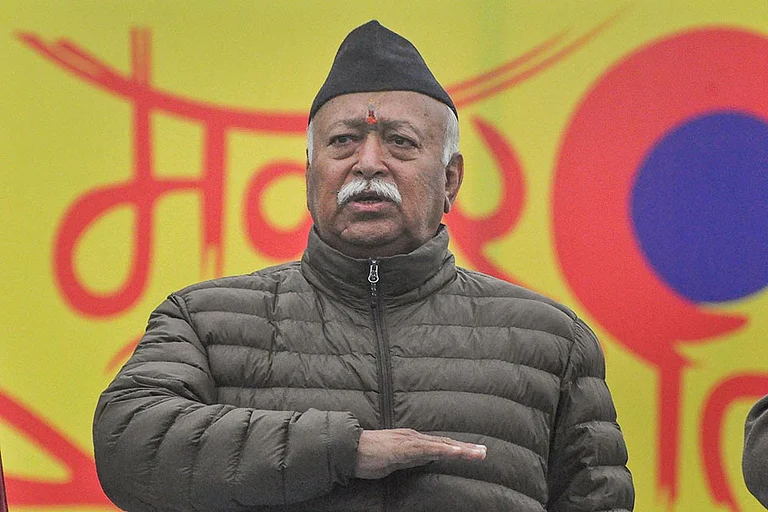

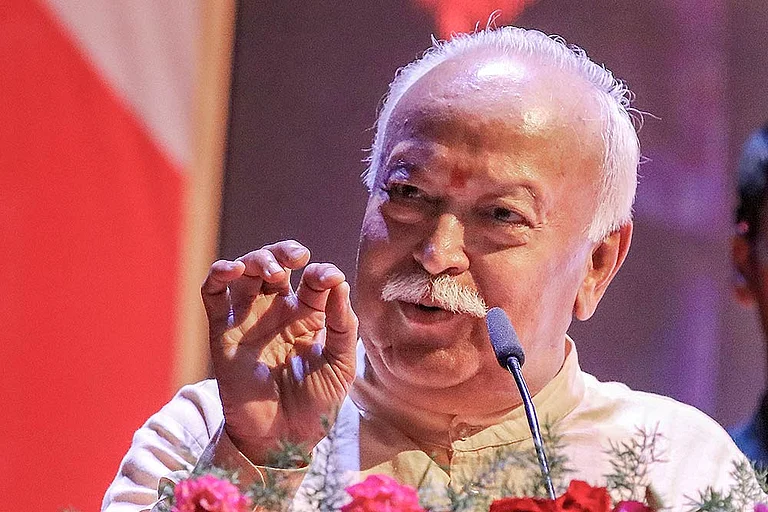

The formation of the RSS was not a split in the Mahasabha, though Hedgewar was loosely associated with it. But it was his conscious choice of different paths that posed a question: Why did India endure slavery in its history despite having immense manpower, resources and other political institutions? He addressed this question at a meeting of the Hindu Yuvak Parishad in Pune in 1938 in the presence of V. D. Savarkar and other Mahasabha leaders. He himself answered it: the country’s unity and integrity cannot be achieved through slogans or political gains alone. It requires missionary zeal, spirit, sacrifice and patience to propagate nationalist literacy among people to awaken a consciousness beyond their caste and religion, regional and linguistic identities. This, from Hedgewar to Mohan Bhagwat, remains the essence of the RSS’ vision and action.

The Mahasabha sought to incorporate the RSS in its political mission and electioneering, but the RSS categorically refused. The young turks of the Mahasabha—Veer Yashwant Rao Joshi, Nathuram Godse, G. G. Adhikari, Madhav Govind Puranik—wrote to V. D. Savarkar: “They deliberately prevent their members from working for the Mahasabha. They cunningly use us to further their own organisational interests.” In fact, many of the Mahasabha leaders, including Savarkar and Moonje, in their later part of life, became outspoken critics of the RSS.

This led a RSS thinker, Sri Ram Gosavi, to say in Mahratta newspaper—established by Bal Gangadhar Tilak—on August 23, 1940: “The Congressmen call it communal and want to hang it, but when I see some of our own, in discreet Hindu sashays, calling the RSS names. I am struck with pain and wish to ask, ‘you too Brutus’.” The RSS regards India as a Hindu nation. It is not a proponent of a theocratic state—a position that both Golwalkar and Bhagwat have clearly articulated at every critical juncture in the discourse on Hindutva.

In an era dominated by a new form of capitalism—which is driven by an invisible capital and neo-liberal ideas—the RSS cannot remain a silent spectator. It upholds decentralisation of wealth and the institution of family, both of which have grown vulnerable under the increasing influence of neo liberalism. A system that often fosters the disintegration of the family and community life essentially contributes to the centralisation of wealth. It causes mechanisation of common people, a cog in the wheel of the economic system promoted by capitalism.

The RSS enjoys a unique advantage of casteless and classless character of its cadres. For instance, Yadav Rao Joshi, a poor orphan, credited with expanding the RSS in Karnataka, and Rajendra Singh of the upper echelons of society were regarded equals in the organisation. RSS cadres come from every caste and class, but the overwhelming majority belongs to the lower and middle classes. In its early years, clerks, school and college teachers and lawyers played a crucial role in its growth. The cadres are indoctrinated not only to confront physical reality, but also to develop a profound understanding of the social and psychological issues facing society.

Most importantly, social and public morality is a distinctive feature of RSS’ exceptionalism. Its cadres have consistently upheld moral principles in dealing with resources and demonstrated they can sustain even without abundant material support, as Hedgewar wrote to a RSS functionary. RSS created new swayamsevaks even in the absence of resources to support it. He introduced the system of gurudakshina—annual contributions by its members. There are several occasions when the RSS turned down generous offers from its sympathisers, like Madan Mohan Malaviya, M. R. Jayakar, B. S. Moonje and a rich lawyer from Nagpur, as well as big contributors like G. D. Birla, who had earlier financially contributed to build the office building of the Mahasabha in Delhi and supported Gandhi’s Harijan Sevak Sangh for decades.

In contrast, the Communists, Socialists and the Gandhian movements suffered from persistent weaknesses in organisational culture. Gandhi, in a letter to the Communist Party General Secretary P. C. Joshi, questioned the funding mechanism of the Communist Party of India. Shankarrao Deo, who held the position of the All-India General Secretary of the Congress, delivered three lectures in 1949 on the decline of the Congress. He attributed this decline to organisation’s ills and the influence of corporate India (zamindars), whose support to the Congress in the 1937 elections had shaped its economic policies.

The RSS’ century long journey is a priceless living legacy of Hedgewar’s vision and thousands of nameless people who contributed to its success. At one time, the RSS had thousands of adherents and millions of opponents, but history has witnessed the reversal of this reality. About this reversal one thing can be said: we must face and understand the facts. The RSS still has a long way to go to realise the goals of cultural nationalism and social and economic egalitarianism. Today’s times demand an astute balance between the two. Lastly, it must vigilantly safeguard the hard-earned its moral boundaries that gives strong support to its vision and action.

(Views expressed are personal)

This article appeared in Outlook Magazine's 21 October Edition 'Who Is An Indian?' as One Hundred Years Of...Growth And Success.