Only 1,808 of 9,000 targeted Dal Lake families were rehabilitated under the 2009 plan; most remain in the lake amid disputes, infrastructure gaps and legal hurdles.

The government has now scrapped large-scale relocation, proposing to convert 58 internal hamlets into regulated eco-friendly settlements.

With shrinking water surface, rising pollution and sewage stress, Dal’s future hangs between conservation goals and the rights of its long-settled communities.

When National Conference legislator Tanvir Sadiq raised a question in the Jammu and Kashmir Assembly about the status of rehabilitation of Dal dwellers, the government’s reply was shocking. The ₹416.72-crore resettlement plan for Dal Lake dwellers had achieved “only 27% progress” in 17 years.

The ambitious project, approved in 2009 under former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and Congress leader Sonia Gandhi, had sought to relocate at least 9,000 families from the Dal Lake ecosystem, set against the backdrop of the Zabarwan hills in Srinagar.

The goal was simple: reducing pollution, saving aquatic life and arresting the lake’s steady shrinkage.

Instead, only 1,808 families were rehabilitated to a colony in Srinagar’s Bemina, one of the most affected areas during the massive floods of 2014. The rest stayed back, some by choice and other due to faultlines in infrastructure, compensation disputes and a High Court stay order.

All these years later, the government has entirely abandoned that model and now it is proposing to transform 58 existing hamlets within Dal lake into “eco-friendly hamlets”. This marks a dramatic turn in the debate that has been going on for years now: are Dal dwellers its protectors or its polluters?

“We Are Part of Dal”

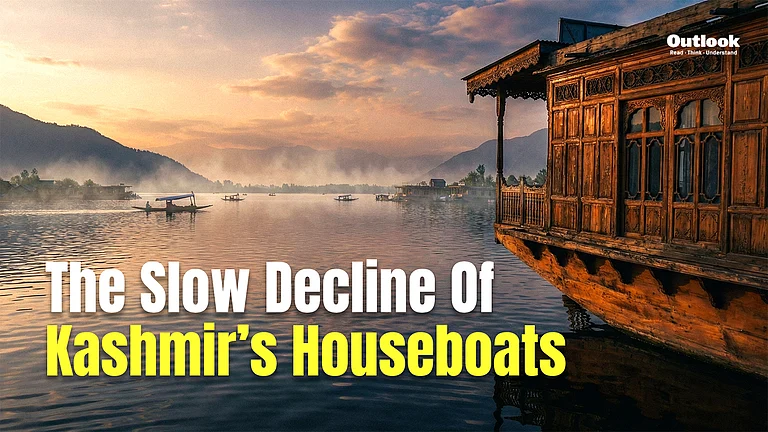

The lake has remained central to Kashmir’s ecology, history and culture and is shaped by centuries of human intervention, all of which has converted the lake into a lived-in landscaped of floating gardens, houseboats and settlements.

Divided into the Hazratbal, Bod Dal and Nigeen basins, the lake has been highlighted in texts such as colonial accounts by Walter R. Lawrence, a British officer who travelled across different parts of Kashmir and later wrote a book 'The Valley of Kashmir’, a comprehensive text detailing the region's geography, history, culture, and social conditions.

Today, though environmentally stressed, Dal Lake continues to remain both a major tourist attraction and a vital source of livelihood, drinking water, fish and vegetables for the local population.

Abbas Kashmiri, a resident of Mir Behri area in Dal Lake, was born in the interior locality of Dal, a place where his seven generations have lived. “The water we cultivate nadru (lotus stem) in, even that has revenue documents. We were given those papers more than 100 years ago.”

Dal dwellers argue they were historically settled in the lake not as encroachers, but as custodians. Their livelihood, lotus stem cultivation, vegetable farming on floating gardens, fishing and weed removal, depended on maintaining clean, navigable waters.

Earlier, residents manually extracted weeds with wooden poles up to 25–30 feet long, removing roots entirely. In recent years, however, the Jammu and Kashmir Lake Conservation and Management Authority (LCMA) started using machines to trim this weed, something that Dal dwellers believe contributed to increasing the growth of weed. “Government machines only cut the top layer,” Kashmiri said. “Roots remain. Then it grows faster.”

Several residents claim that when authorities restricted agriculture and seized boats used for manual de-weeding, the ecosystem began deteriorating. Gradually, the younger generation began shifting from farming to tourism, transport and government jobs.

Yet the stigma remains. “People say the Dal is dirty. They don’t give daughters in marriage here,” Kashmiri said, adding that people still believe that Dal dwellers don’t even have proper toilets.

Another resident of Dal, who wished to stay anonymous, said 98 per cent of Dal dwellers initially did not want relocation. “Earlier, we conserved Dal because our livelihood depended on it. Crores worth of vegetables were grown. The ecosystem and livelihood were both safe.” But construction bans, demolitions and uncertainty forced some to move. “It was not voluntary, it was pressure.”

A failed experiment

Under the 2009 rehabilitation plan, 7,526 kanals of land were acquired in Bemina. Each family was allotted a plot, ₹1.05 lakh for construction and ₹3.91 lakh as one-time compensation.

But infrastructure lagged behind. Residents complained of flood-prone land, inadequate drainage and lack of livelihood options. Many returned to Dal.

Environmental activist Raja Muzaffar called the 27 per cent progress figure “a clear failure.”

“If in 17 years you could rehabilitate only 25–30 per cent, that itself shows there was no proper consultation,” he said. “No dialogue with experts, no proper policy.”

He argued that the dominant narrative unfairly blamed Dal residents but not much was said about the urbanisation that took place around Dal Lake including big hotels and localities. “Urbanisation in Harwan, Nishat, Shalimar, Boulevard Road contributes massively. Maybe 10% of the pollution comes from residents,” he said.

Muzaffar insists eviction is not the solution. “If you remove someone from their habitat, what will happen to them? Across the world, indigenous communities are made partners in conservation.”

Faced with stalled rehabilitation and legal complications, the government has now pivoted.

It told the Assembly that 58 internal hamlets would be developed as eco-hamlets under an in-situ conservation model. Work on six has begun under the UT Capex budget, including Kachri Mohalla, which it describes as a “modern village”.

As per a report by Down To Earth, a Joint Committee constituted by the National Green Tribunal in August 2024 reported that buffer zones had been established along the entire periphery of Dal Lake to curb encroachments, noting that the lake and its backflow channels, Nayadar and Jogilankar, had become nearly anaerobic due to high organic pollution levels of up to 23.5 mg per litre. During an October 2024 inspection of Dal and Nigeen lakes, the panel reviewed sewage and solid waste infrastructure managed by LCMA, which reported that 52.40 MLD of sewage was generated from 18 municipal wards.

As per figures shared with Outlook by LCMA, ₹212.38-crore Integrated Management Programme for conservation of the Dal-Nigeen ecosystem has been accepted in principle by the Union environment ministry and awaits final financial approval.

Muzammil Rafiquee, Superintending Engineer at LCMA, said the revised Detailed Project Report (DPR) focuses on sewage treatment, revival of interlinking channels and regulating carrying capacity. “About 80% of pollution load is covered through sewage treatment plants. The remaining 20% is under process,” he said, adding that no new houseboats are being permitted and that floating gardens will be regulated within ecological limits.

The Ecological Debate

Environmental activists question whether infrastructure promises will translate into reality. Manzoor Wangnoo, president of the Nigeen Lake Conservation Organisation, said that he supports regulated in-situ rehabilitation but warned that the lake’s condition is precarious.

“The navigation system has collapsed in many areas,” he said. “Channels are choked. If drainage is not fixed, even five days of heavy rain can create a crisis like 2014.” If backed by proper sewage systems and channel restoration, Wangnoo said that eco-hamlets can preserve both ecology and culture where Dal and its dwellers have co-existed.

Others are more sceptical. An environmental researcher, speaking on condition of anonymity, said Dal’s area has shrunk from roughly 25 sq km to about 11 sq km of clean water surface. “Dal is under pressure from habitation, hotels, tourism and catchment erosion,” he said, explaining that nitrogen levels have increased due to human waste and fertilizer runoff. “That leads to eutrophication and reduced oxygen.”

He questioned the feasibility of permanent settlements within the lake and said that in modern times, people cannot survive without basic infrastructure such as roads, hospitals, schools. “If land is filled to create infrastructure, Dal will shrink further. Its carrying capacity has already exceeded,” he said.

Dal also lies near Dachigam National Park and Salim Ali National Park, Himalayan wildlife sanctuaries famous for protecting the critically endangered Hangul (Kashmir Stag), raising questions about eco-sensitive zone regulations and Supreme Court guidelines restricting new activities within 10 km of protected areas.

An Unresolved Future

Around the world, many communities live on water. In Indonesia’s floating villages in Borneo, in parts of the Philippines and Malaysia, and even in Southeast Asian urban waterfronts, habitation coexists with strict waste management systems and modern sewage infrastructure.

Muzaffar, the environmental activist avers that instead of displacement, Kashmir should study such models. “Install functioning STPs. Ensure door-to-door waste collection. Enforce solid waste rules. Collect ₹100 a month if needed. But don’t uproot people.”

Wangnoo agrees. He says the possibility of coexistence is higher with scientific planning. “Dal once represented purity. Tourists inhaled its air deeply. It can be restored, but priorities must change.”

For now, Dal’s future hangs between two unfinished models: a failed relocation scheme and an unapproved eco-hamlet proposal. For residents like Kashmiri, the issue is not policy language but dignity. “We can survive outside,” he said. “But Dal is our home.”