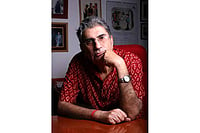

The fiction writer Sanjeev was recently announced as the winner of the Sahitya Akademi Award 2023 (Hindi) for his novel Mujhe Pehchano. The work is centred on the life of the sister-in-law of Raja Ram Mohan Roy, one of the architects of Indian Renaissance. With the oppression of Sati for its core theme, the book delves into the exploitation of women and brings forth issues of modern as well as pre-modern Indian societies. It is an exemplar of the balance between meticulous research and engaging storytelling that has characterised Sanjeev’s writing from the beginning.

After Premchand, (and Phanishwar Nath) Renu Sanjeev is, arguably, one of the most important chroniclers of our villages and small towns. In his works one can easily discern characters forged in grassroots struggles and filled with mental and ideological yearnings. Over the course of his creative journey, Sanjeev has penned over one hundred and fifty stories and a dozen novels. Stories like ‘Bagh’, ‘Derh Sau Salon Ki Tanhai’, ‘Tirbeni Ka Tarbanna’, ‘Sagar-Simant’, and ‘Arohan’ are not only individual achievements of the writer but a credit to the entire Hindi literature.

His novels such as Panv Tale Ki Doob, Jangal Jahan Shuru Hota Hai, Dhar, Phans, Sutradhar, and Mujhe Pehchano belong to the same thematic terrain as his stories. One finds a surprisingly diverse array of subjects in his narrative world, though, at heart, all his writings deal with the same everyday problems of the countryside, towns, and forests. In them, one encounters external and internal conflicts of the coal mines, caste struggles via Bhikhari Thakur, Naxalbari-influenced political combativeness, the reality of circuses, and so on. The feudal values that persist within all these spaces are laid bare. In the words of eminent story writer and editor Rajendra Yadav, “Sanjeev’s stories are vanguard battalions of the resistant consciousness confronting feudal terror.” This explains why in these works, his personal self is in abeyance, and themes such as love and sex evanesce in the heat of the struggle he portrays.

Sanjeev was an inhabitant of the world of fiction writing, but he was not at its centre. After cities such as Allahabad and Banaras receded into the background and Delhi emerged as the centre of Hindi writing, the writing from the peripheries were deemed outsiders. Though dozens of scholars conducted research and magazines published special issues on Sanjeev's works, he did not quite achieve the same preeminence as his contemporaries Uday Prakash and Shivmurti. This could be attributed to an authorial impersonality in Sanjeev's fiction-verse, and the fact that his works revolve around the Dalits, tribals and a world of struggles. His critics blame it on the “dryness” and “detachment” of his writings. To be sure, there is no tenderness of love in his works, and he does seem to be of the view that those who engage in struggles do not love. However, in saying this, one cannot discount the feudal mindset of the Hindi social sphere. It is well known that as a writer, Sanjeev is firmly on the side of the forgotten and forsaken. In his stories, we hear the voice of those for whom the doors of the panchayat, courts, and the parliament are all closed. This is not an exception but the norm permeating all his writings.

In Sanjeev's works, the voice of progressiveness has always rung loud and clear. In this regard, his novels are stronger than his stories. This is because the broad and detailed canvasses of his narratives find better expression in the novels than in the stories. Critics acknowledge his commitment to content but consider him unyielding in his craft. It is this predilection of Hindi criticism towards the miracle of craft that deprives Sanjeev of his rightful dues. The increasing fascination with descriptions of clubs, sex, etc. in writing has also been inimical to Sanjeev's characters and their milieus, causing them to disappear from the world of Hindi literature. Writers like Sanjeev, who take up cudgels against the system and relentlessly expose its flaws, have been pushed to the margins. When one writes on the nexus between power and capital, it is rather a given that one will be targeted for the deficiency of one's craft.

A prime example is his novel Phans, based on the woes of the farmers of Vidarbha. It depicts the entrapment of the Indian cultivator in a post-modern society in its multidimensionality. The way it illustrates the social reality of the Dalits and lower classes hews very close to his stories. In depicting the way the upper echelons of the Hindu social order are ranged against the Dalits and Adivasis, the writer forcefully foregrounds the chokehold (phans) exerted by religious beliefs and social customs.

Sanjeev is among the rare Hindi writers who chose and steadfastly remained on the side of the marginalised in their writing and their ideology, and did so with great maturity. The Akademi Award has been long in coming. Perhaps, he was a contender for it right from the days of Phans and Jangal Jahan Shuru Hota Hai. But as the saying goes, better late than never, and arguably, the award signals an acknowledgment of both the writer and the centrality of public concerns to his writings.

Translated by Kaushika Draavid