Summary of this article

His passing marks the end of an important chapter in Indian intellectual life

He demonstrated how caste could not be understood in isolation from economic class and political authority

Béteille did not merely interpret Indian society. He helped give Indian sociology its modern methods.

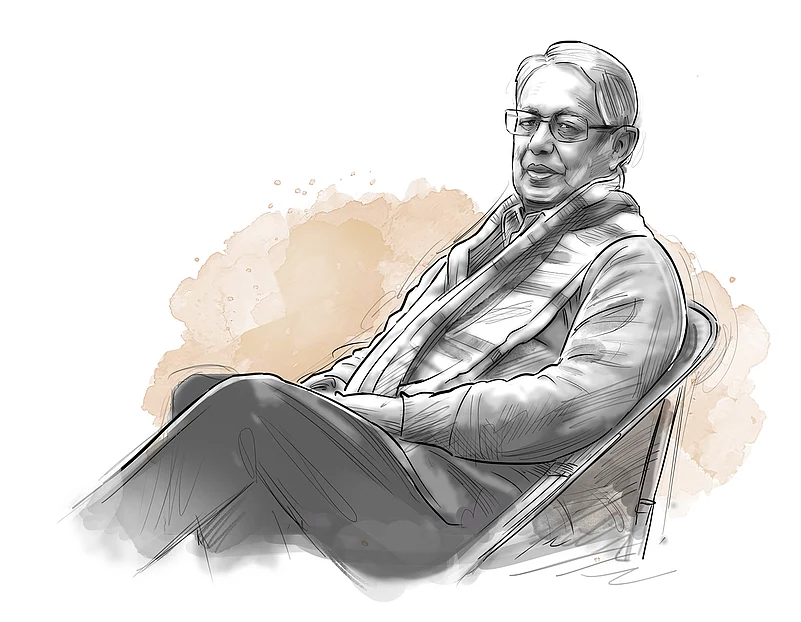

The news came not as a formal announcement or a front-page headline, but through a brief post by the historian Ramachandra Guha on X. Its tone was restrained, almost understated, yet unmistakably final. André Béteille, among the most influential sociologists India has produced, was no more.

The way the news arrived felt fitting. Béteille was a thinker who distrusted spectacle and avoided intellectual grandstanding. His work unfolded quietly over decades, shaping how Indian society is studied, debated and understood, often without drawing attention to itself.

For many of us who studied social sciences in Indian universities in the early 2000s, Béteille was not a distant academic figure but a formative presence.

Learning to see and to think

In the corridors of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Banaras Hindu University in 2002, I first encountered the formidable work of André Béteille not long after I began immersing myself in the study of Indian society. Alongside giants such as M.N. Srinivas, his writings soon became landmarks in my intellectual journey.

While Srinivas taught us to see Indian society through detailed village ethnographies and to listen to its rhythms and lived experiences, Béteille encouraged us to think it through. He asked us to attend to the structures and forces that shape inequality, power and social change, with the precision of a watchmaker and the moral clarity of a disciplined thinker.

If Srinivas foregrounded memory and practice, Béteille foregrounded structure and comparison. Together, they shaped how an entire generation learned to approach Indian society.

A life shaped by inquiry

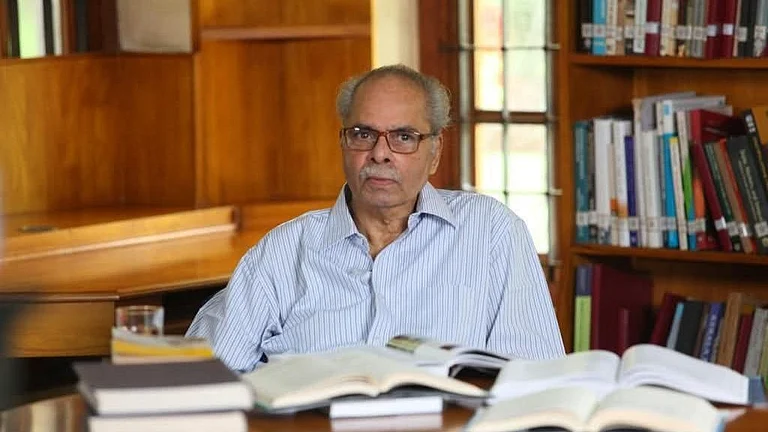

Born in 1934, André Béteille belonged to a generation that faced the challenge of understanding Indian society in the aftermath of Independence. The inherited categories of colonial knowledge were no longer sufficient, yet the new democratic order had not erased older hierarchies.

Educated in Calcutta and Delhi, Béteille spent much of his academic life at the Delhi School of Economics. He also taught at institutions such as Oxford, Cambridge, the London School of Economics and the University of Chicago. Despite his international standing, his work remained deeply rooted in Indian realities.

His early and seminal book, Caste, Class and Power (1965), based on fieldwork in a Tamil Nadu village, fundamentally altered the study of social stratification in India. At a time when caste was often treated as a self-contained system, Béteille demonstrated that it could not be understood in isolation from economic class and political authority.

Rethinking inequality

Across later works such as Studies in Agrarian Social Structure, Inequality and Social Change, Society and Politics in India and Antinomies of Society, Béteille returned repeatedly to the question of inequality.

He argued that social hierarchies are not frozen inheritances from the past. They are shaped by education, land ownership, political access, and institutions of modern governance. His insistence on examining caste alongside class and power reshaped Indian sociology and influenced how inequality is studied globally.

Béteille was sceptical of both cultural romanticism and ideological certainty. For him, critique had to be informed, and reform had to begin with understanding.

The discipline of thought

I spoke to Prof Badri Narayan, Vice-Chancellor of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, after learning of Béteille’s passing. Reflecting on his intellectual legacy, he said to me, ‘André Béteille taught us that sociology is not about instant verdicts. It is about discipline, of thought, of language, and of evidence.’

This discipline was evident in Béteille’s public writing as well. Through essays and columns later collected in volumes such as Chronicles of Our Time, he addressed reservations, secularism and democracy without simplifying complex questions for easy agreement.

Prof Badri Narayan emphasised that André Béteille did not merely interpret Indian society. He helped give Indian sociology its modern methods. His work offered a disciplined way of thinking about caste, class, inequality and institutions, grounding moral concern in empirical rigour and comparative analysis.

A public intellectual without noise

Béteille represented a model of public intellectual life that now feels increasingly rare. He believed that ideas mattered because they shaped institutions and lives, and that careless thinking carried consequences.

As Prof Badri Narayan added, “Béteille’s legacy lies in teaching us how to think, not what to think. His work remains relevant because it does not age with political fashion.”

Despite receiving honours such as the Padma Bhushan and international fellowships, Béteille remained committed to intellectual humility and rigour.

Why Béteille still matters

Why should André Béteille be remembered today? Not only because he reshaped Indian sociology, but because he demonstrated that clarity and complexity can coexist. He showed that restraint is not a refusal to take sides, but a way of taking society seriously.

For students like me, his influence extended far beyond examinations and classrooms. He shaped habits of mind that remain essential for understanding a deeply unequal society.

His passing marks the end of an important chapter in Indian intellectual life. Yet the questions he raised, about inequality, power and democracy, remain unresolved. The method he insisted upon remains urgently necessary.

In that sense, André Béteille continues to speak, quietly but persistently, through the discipline of thinking he left behind.

Ashutosh Kumar Thakur is a writer and columnist based in Bangalore.