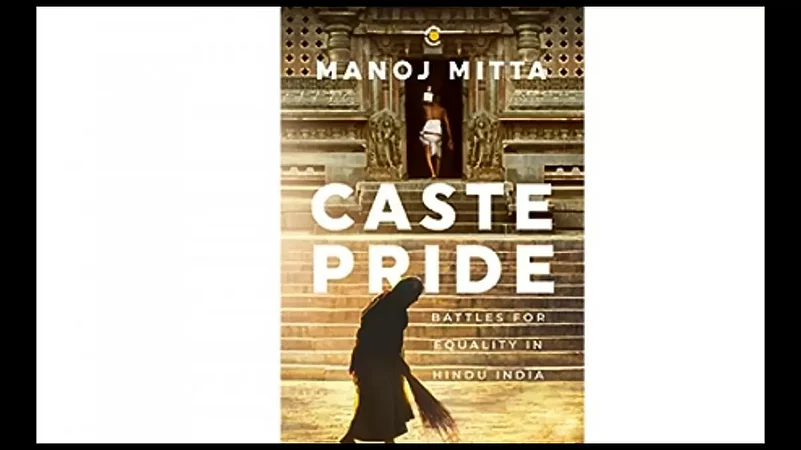

Manoj Mitta- Caste Pride: Battles for Equality in Hindu India

The New India Foundation-2023

The author needs to be complimented for his painstaking and meticulous research which includes archival sources to clarify the mutating nature of caste and its lived realities. The title itself hits the nail on the head- ‘Battles for Equality in Hindu India’, a mirror to those who deny the existence of caste and its oppressive system.

The book is organized into five sections and eighteen chapters and delves into legislative, judicial and government records to map the trajectory of caste, especially in the past two centuries-from the early codes of punishment, the various provisions given by the colonial state to exempt upper castes from serious punishments, the breast cloth controversy, various struggles for temple entry, to the judgment delivered on the Khairlanji caste atrocity in 2019.

The very first chapter, ‘Early Codes: Punishment Reserved for Lower Castes’ hooks the reader with the discussion on caste laws and their relationship with jurisprudence. The compendium of legal cases helps the reader to understand the ambiguities around caste that continue to persist today despite efforts to create a more egalitarian society. The legal system often denies the relationship between caste and law and hence it is difficult for people, lower in the hierarchy to access justice. I have witnessed similar punishments being meted out to Dalits and backward castes in my village in united Andhra Pradesh by caste panchayats. It is a constant battle to impose constitutional values in a caste-embedded society. Mitta brings to light the hesitation of various nationalist leaders to deal with caste and also the continuous tussle by various unsung leaders to confront the monster of caste. He provides data to substantiate his arguments. To illustrate, in the decade of the 1950s and 60s, there is a marked difference in the convictions under the Untouchability Offences Act. The reason was the Act was being subverted in several sinister ways (Ch 12). Even if convictions were handed out, the accused were able to get away with just a small fine. Thus, even after untouchability was formally abolished, it morphed into new forms. The discussions in Parliament on the various aspects of the UoA Bill under different political regimes help to contextualize the wider socio-political realities in society. Mitta’s concluding remarks in this chapter is very poignant, “Since 1919 when M C Rajah was appointed the legislator, the battles fought in the legislature, executive and judiciary testifies to the resilience of the caste prejudice…” (p 337)

A few days ago, there was a controversy when the first citizen of the country-President Murmu (the first tribal woman to grace the post of President) was denied entry into the sanctum sanctorum of the Jagannath temple in Delhi and the servitors stated that only if ‘they’ invite the worshipper can the latter enter the sanctum and offer worship (BBC News Hindi, 20 June 2023). This reflects how caste rules of purity and pollution continue to flourish in contemporary India. Manoj Mitta begins his chapter on Temple Entry with a similar observation. On 11th September 1893, Swami Vivekananda delivered an eloquent address to the Parliament of Religions in Chicago. He credited his spiritual conquest (p 341) to Raja Sethupathi, the zamindar of Ramnad who supported his ideas and urged him to go to Chicago. A few months later, the same Raja was instrumental in filing a suit against a few lower-caste men who had entered a temple of which he was the hereditary trustee. Equally interesting is to note about the ambiguous stand of Vivekananda on caste. While defending varna in its original form, he denounced untouchability. He too was a victim of caste prejudices as he had to wait for three days at the Kodungallur Bhagavathy temple in Cochin in 1892 as the temple authorities could not determine his caste (p 342). The chapter provides intricate details of the legal tussle on the issue of Dalit entry into temples. It also highlights Ambedkar’s struggle to ensure that the Hindu Untouchable Castes (Removal of Disabilities) Bill of 1929, applicable in British India, would acknowledge that the untouchable was as much a rights-bearing individual as any other Hindu, whether in secular or religious spheres. The larger national politics also had an impact on the various temple entry movements and the eventual disengagement of Ambedkar with such movements.

Post Independence, with the Constitution guaranteeing equal rights to the untouchables and various other social and legal provisions to ensure their well-being, one would think that gradually, society has evolved to become more inclusive. This complacency was shattered by the Kilvenmani massacre of 1968 in Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu where a mob burnt alive forty-two untouchables, mostly women and children. The victims were rendered so vulnerable that they were unable to render any defence. This gruesome incident revealed that instead of caste gradually withering away, caste supremacists have weaponized mass destruction of the community as a form of punitive action. Similar incidents occurred in many other states with the law enforcing machinery remaining a mute spectator and the judiciary failing to provide any relief. In 2006, Khairlanji witnessed four members of a Dalit family being lynched by a mob. The Supreme Court conveniently failed to mention the sexual violence against neither the female victims nor the word ‘caste’ in connection with the atrocity. More recently, we have witnessed Hathras which has ushered in a new narrative in the trajectory of caste violence wherein the victim is denied dignity even in death.

In the present times, when Dalits are being wined and dined to gain their votes and social harmony is bandied around to win political mileage, Manoj Mitta’s book is a timely reminder that caste continues to flourish under modernity, its banality giving way to more insidious forms of oppression and discrimination. Finally, the author needs to be congratulated for writing a book free of academic jargon, in a language which is easy to understand by students and scholars alike.

(N Sukumar teaches Political Science at Delhi University. His research areas include political theory, anti-caste studies and higher education. (nsukumar@polscience.du.ac.in))