Summary of this article

Actor R. Madhavan received the Padma Shri, India’s fourth-highest civilian award, this year.

The actor, once marketed as liberal and urbane, has increasingly emerged as a vocal admirer of the Prime Minister and the BJP’s nationalist project.

He has become a part of a growing cohort of film celebrities who have discovered that proximity to power is ultimately more profitable.

Ranganathan Madhavan’s arrival in Hindi cinema occurred 25 years ago with the commercial flop Rehnaa Hai Terre Dil Mein (2001), playing a romantic lead who was considered a textbook red flag boyfriend even before the terminology had entered our pop culture lexicon. As luck would have it, the television re-runs of the film, the soulful soundtrack by Harris Jayaraj, and an approachable screen presence ensured that Madhavan eventually became a national heartthrob. The thousand-mile journey from being a national heartthrob to becoming Indian nationalism’s latest poster child recently culminated with Madhavan receiving the Padma Shri, India’s fourth-highest civilian award, this year.

Madhavan’s public persona over the last decade has undergone a quiet but decisive shift. Where the Rang De Basanti (2006) actor was once marketed as liberal and urbane, he has increasingly emerged as a vocal admirer of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the BJP’s nationalist project. His praise has been consistent and with an enthusiasm that places him firmly within a growing cohort of film celebrities who have discovered that proximity to power is ultimately more profitable.

This ideological alignment found explicit cinematic articulation in Aditya Dhar’s Dhurandhar (2025), the propaganda spy thriller that claims fictional status while leaning heavily on recognisable political history. The film adopts real terror incidents—Kandahar, Parliament, 26/11—as raw material repurposed to reinforce a specific narrative. However, by recasting historical anxieties through a lens that lionises the current government and assigns culpability to political opponents without evidence, Dhurandhar participates in the very politics it claims to fictionalise. This approach blurs fact and fantasy in ways that validate a partisan reading of India’s recent history.

But it isn’t Dhurandhar that marks Madhavan’s arrival as a cinematic emissary for the state. Rocketry: The Nambi Effect (2022) was like a personal crusade for him. He not only played the titular role in the film but also directed, wrote, produced, and even penned lyrics for the project. Shot across continents and released in multiple languages, Rocketry was conceived and executed as an attempt to settle history and public memory in one sweep.

Critics noted how insistently the film underlined Narayanan’s Hindu identity—prayer rooms, rituals and devotional gestures. The film also leaned into a north Indian gaze that collapses Tamil identity into a familiar Brahminical template. Rocketry also framed Narayanan’s life through an interview with Shah Rukh Khan. That a Muslim superstar, previously vilified by the same political ecosystem Madhavan now courts, is positioned toward the end of the film to ask forgiveness on behalf of the nation is a narrative choice that felt symbolic; almost as if it were a public form of humiliation ritual.

During Rocketry’s promotions, Madhavan suggested that ancient Hindu calendar, the panchangam, had provided precise astronomical data used in modern space missions. The statement fitted right into the popular nationalist mythos that has been attempting to retrofit modern scientific achievement into Hindutva legacy. The claim was of course scientifically nonsensical and was swiftly corrected by scientists and mocked online. Madhavan later clarified that he had misspoken, attributing the error to linguistic confusion.

Even outside these films, Madhavan’s public persona has increasingly fused cultural pride with supremacist ideologies. In 2019, Madhavan shared an Independence Day Instagram post featuring himself, his father, and his son all wearing a poonal/poite (sacred thread) as a celebration of faith and tradition on the occasion of Avani Avittam. However, the sacred thread is not a benign religious adornment; it is a definitive marker of caste pride that is historically tied to Brahminical privilege. Madhavan has also made bigoted remarks about polygamy in Muslim communities in wretched attempts at humour at the Radiant Wellness Conclave and again at ‘India in 2030’ at Harvard University.

These moments form a continuum rather than a series of slips. They signal allegiance to a majoritarian idea of heritage—one that romanticises tradition and treats cultural assertion as beyond critique.

Cinema, propaganda, and power

Hindi cinema has never shied away from nationalism and audiences are well-versed in its emotional shorthand. The problem is that films like Dhurandhar and Rocketry deliberately weaponise ambiguity. They perform an ideological sleight of hand to rewrite collective memory under the guise of entertainment.

Madhavan’s popularity lends the characters he plays a veneer of legitimacy and likeability. When in Dhurandhar he, as Ajit Sanyal (a character heavily inspired by Ajit Doval, National Security Advisor of India), delivers a line about the eventual arrival of a government that truly cares for the nation, “Ek din aayegi aisi sarkar, jise desh ki fikr hogi,” it is meant to be read as a wilful endorsement of the powers at the helm right now.

Cinema has long been a space where ideology and imagination intersect. The difference between art that interrogates power and art that upholds it without reservation is not trivial. It shapes how audiences, especially impressionable ones, understand their place in the political and cultural zeitgeist.

The timing of Madhavan’s Padma Shri, his appointment as President of the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in 2023, should only deepen our concern. FTII has been a site of recurrent debate about autonomy and artistic freedom, with successive governments clashing with students and faculty over institutional direction. Placing a commercially successful actor, who is already vocal in his political sympathies, at the helm of such an institution like a moral and political watchdog is a strategic move. And honours like the Padma Shri, despite being markers of achievement, can also function as instruments of soft power. Who and what the establishment deems worthy of felicitation and amplification through these rewards is always telling.

Which brings us to Leni Riefenstahl, the German propaganda filmmaker. Riefenstahl rose to prominence in the 1930s. Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938)—the latter’s coverage of the Berlin Olympics shaped how the modern Games would be broadcast for decades—were explicit in their messaging. These were not accidental endorsements. Riefenstahl’s works were commissioned, celebrated and elevated by a government intent on swaying public opinion to consolidate its authority.

After 1945, Riefenstahl’s career as a filmmaker effectively ended. For a time, Riefenstahl did enjoy a kind of cultural rehabilitation in certain Western liberal intellectual circles, particularly among those eager to celebrate a pioneering woman in fields historically dominated by men. This rehabilitation was revealing of a feminism that is stripped of political literacy and intersectionalism. For years, Riefenstahl found platforms to reiterate boldly that her work was not propaganda. History, however, proved less forgiving. Today, she is remembered as a case study in how art can serve authoritarianism while insisting on its own innocence.

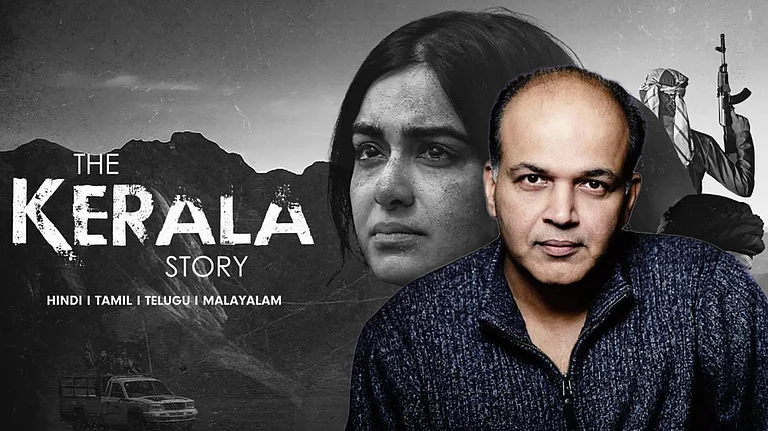

Times change, but the mechanism remains familiar. Artists of credibility lend their craft to dangerous dogma, followed by institutional validation. In the present, the truth may get drowned out by applause and jingoistic fervour, but history has a longer memory. Fascists are always remembered for who they were. If today's cultural figures seek both the laurels of mainstream success and the uncritical embrace of political authority, they too risk a similar fate. Figures like Madhavan, Kangana Ranaut, Akshay Kumar and Ashutosh Gowariker too will be remembered for what their creations came to represent at a fraught historical moment in time, technical finesse of their art be damned.