Summary of this article

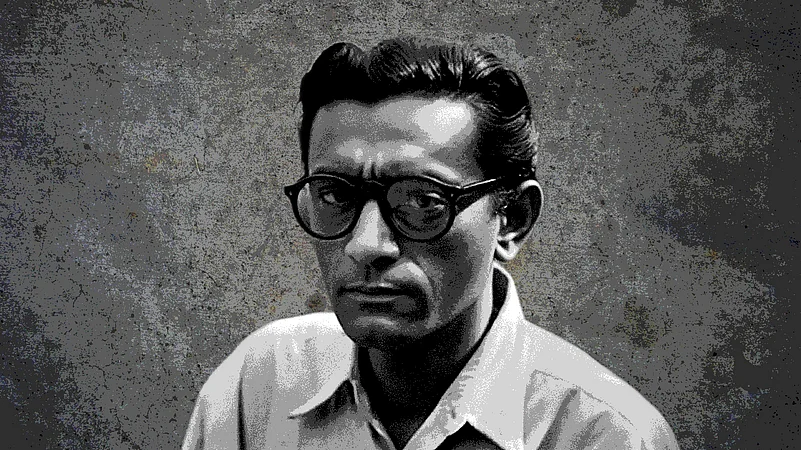

The iconic Urdu writer Saadat Hasan Manto died on January 18, 1955.

He loved the city of Bombay and even after moving to Pakistan post-Partition, he kept yearning to return.

Manto used his acid wit and moral audacity to observe and analyse the people around him, from Bombay’s underclass to its biggest stars.

In the 1940s, during his heydays as a film journalist, Saadat Hasan Manto wrote some of the most salacious, invasive and gleefully indiscreet accounts of Bombay’s film celebrities. Provocation, the most effective tool in Manto’s repertoire, played a role in the pieces he wrote. The most scandalous portraits of Bombay cinema’s golden age did not come from contemporary chroniclers of celebrity sleaze (like some Seema Chandoke of yore), but from Manto, the maverick writer and egomaniacal bard who loved Bombay with his entire soul.

Manto used his acid wit and moral audacity to observe and analyse the people around him, from Bombay’s underclass to its biggest stars. His relationship with the Hindi film industry is often softened in retrospect, framed as a tragic misunderstanding between a literary genius and a shallow commercial world. This version is comforting but largely false.

Manto did not merely brush up against Bombay cinema, he immersed himself in it, fed off it, and wrote about it with a relish that was frequently and unapologetically invasive. In his writings, the people were stripped off their fabricated aura and presented just as they were—undignified, excessive, compromised, and relentlessly exposed. His writings carried the city’s nervous energy, its gossip economies, its transactional intimacy.

Through Manto’s lens, Bombay and its creatures went beyond what postcards or myth-making would have us believe. This was the Bombay of underpaid writers, inflated egos, drunken nights and studios that extracted labour while pretending to nurture art. “I stayed in Bombay for twelve years,” Manto once reflected, “I am what I am because of those years. There were times in Bombay when I did not have enough to eat and there were times when I was making vast sums of money and living it up. That was the city I loved. That is the city I still love.”

In one early-1940s incident, Manto staged a hunger strike to recover his dues from a producer who refused to pay his full wages. He worked as a prolific screenwriter and radio dramatist for major studios like Filmistan and Bombay Talkies. He wrote screenplays for films such as Shikari (1946), Aath Din (1946), Apni Nagariya (1940), and later Mirza Ghalib (1954), a film that would become a commercial success in India even as Manto died impoverished in Lahore.

His autobiographical account Meena Bazaar, first published in 1962, was not a simple reminiscing of the good times and company he kept in Bombay. It was a careful and nigh shameless deconstruction of himself as well as the film industry’s carefully curated self-image.

In Stars From Another Sky (2010), particularly the essay “One in a Million,” Manto wrote about the singer Noor Jehan’s metamorphosis from a child performer into a fully-grown charmer on-screen in the same breath he detailed her affair with director Syed Shaukat Hussain Rizvi. He did not hesitate before going a step further and writing about the rumours of her siblings running a brothel near Cadell Road, close to Shivaji Park.

In his profile of Naseem Banu, Saira Banu’s mother and one of India’s earliest female superstars, Manto disclosed the abject ordinariness of stardom as he noted how Banu lived in a modest bungalow in Thane and had a bathroom devoid of “exotic soaps” or “bath salts”. He appraised the legendary Kathak dancer Sitara Devi both as a “typhoon” for her powerhouse persona and as a “man-eater” for her ribald appetite for extra-marital affairs. Manto stripped his dear friend Ashok Kumar, aka Dadamoni, of his matinee bravado as well. According to him, the shy Kumar simultaneously wanted female attention, but became paralysed when it came his way.

Despite his proximity to celebrity, Manto remained scathing about Hindi cinema’s creative stagnation. He brandished in his critiques that the film industry’s so-called dream merchants were “old, old-fashioned and simple-minded,” incapable of progress. No art, he argued, could emerge from those whose lives were “like still water.” This is a critique that aged uncomfortably well. Manto’s observation was nothing short of a prophecy, given the state of the creatively regressive and bankrupt ecosystem that is Bollywood today.

Long before his death, Manto wrote his own epitaph with characteristic arrogance: “Here lies Saadat Hasan Manto. With him lie buried all the arts and mysteries of short story writing. Under tons of earth he lies, wondering who of the two is the greater short story writer: God or he.”

Despite opposing Partition in principle, Manto migrated to Pakistan in 1948, attempting to convince fellow-wayward free spirit Ismat Chughtai that Pakistan was the promised land Indian Muslims had been waiting for. She refused and reportedly called him a coward for leaving. In Lahore, Manto’s life disintegrated. Work became scarce; money scarcer. His alcoholism worsened. He died in 1955 at just 42, pining for Bombay, the city that had broken him and made him.

Debiparna Chakraborty is a film, TV, and culture critic dissecting media at the intersection of gender, politics, and power.