Summary of this article

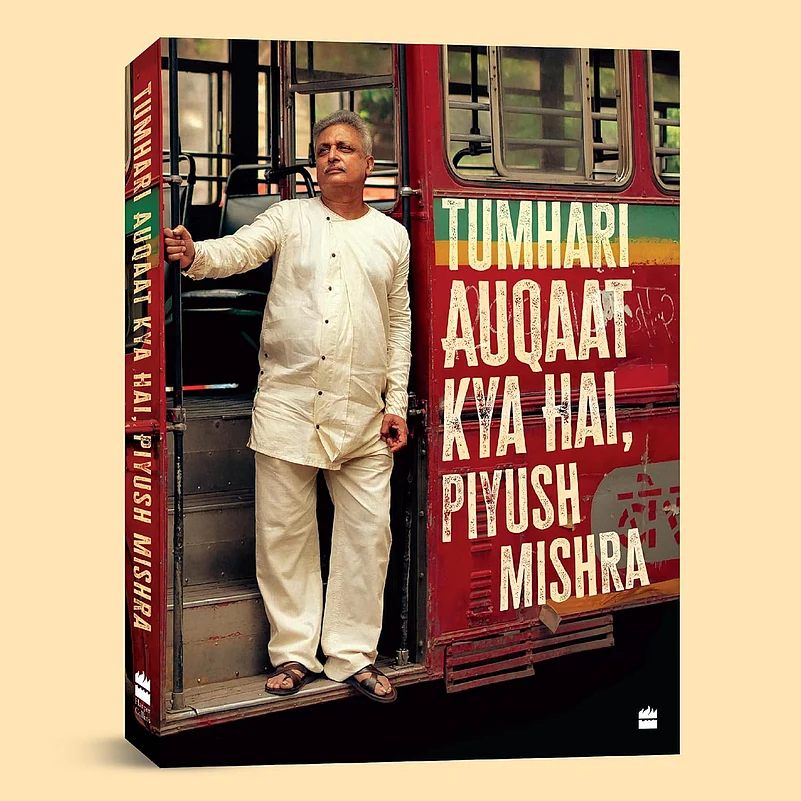

Translating Piyush Mishra’s memoir demanded total surrender to his voice, colloquial style, and emotional depth beyond mere language.

The book reveals a life of relentless quest, trauma, addiction, rage, gratitude, and artistic reinvention through unflinching self-exposure.

Key lessons include channeling fear and rage creatively, choosing battles wisely, practising gratitude, and accepting life’s unresolved tensions.

The translation project that serendipitously came my way felt like a cosmic conspiracy. I agreed without blinking—perhaps even in the same breath. I was, however, gently advised to pause and ponder whether I was fully “prepared” for the assignment, and to be doubly sure before committing. There was, of course, no Hamletian dilemma. It was had “to be.”

This, after all, was precisely what I had hoped for—and perhaps more. His writings—prose, poetry, drama—had been my first touchpoints to understand the man through his words. That was all I had before beginning my third translation project. The brief was clear: keep the colloquialism intact; miss not a beat. It has to read like him.

I came to Tumhari Auqaat Kya Hai as a translator, but very quickly realised that this was a book that would not allow me to remain one. It demanded preparation, attention, introspection, reflection and a particular linguistic alertness that went beyond language, a woman becoming a multi-faceted man like him. The translation project, unlike any other, often led me back to Gwalior-born poet Nida Fazli’s words, with minor tweaks, if I may:

“Qadam qadam dushvārī hai… sahl na jaano bahut baḍī fankārī hai…

ham bā-izzat nikal aaye is basti mein… har (panna) shāista rehna korī duniyādārī hai.” The task that lay ahead was daunting, easier imagined than accomplished. Translation, or rather re-creation, demanded courage and conviction: the willingness to be him, if only briefly. I leaned on my brother and dear friend for counsel; their faith in me was steady. Yet I knew, in my heart of hearts, that every word required complete surrender to the wordsmith called Piyush Mishra, before gently leading him into another tongue, and watching him claim it anew.

Spanning nine months, the exercise remains one of the most challenging, enriching, and fulfilling experiences of my professional life, living, as I did, the many lives of a man who is a master of his craft: acting, writing, singing, composing, and, above all, a soul yearning to be understood in all its shades, black, white, and grey.

What Stayed With Me

From the very first sentence, he makes it raw and unsettling, yet offers glimpses of who he was, who he has become, and who he continues to be; of the places where he lived, loved, lost; and of how those space, times and their experiences shaped him creatively and artistically. What struck me most was how unabashedly he speaks of his passion and purpose, with a clear resolve to be better than he was yesterday and to be the best he can be today.

To me, Tumhari Auqaat Kya Hai, Piyush Mishra, reads as a life lived in five acts—restless, unresolved, and defiantly unfinished—much like its protagonist, Hamlet alias Santap Trivedi, aka Piyush Mishra. What unfolds is a play staged between struggle and survival. This is not an interpretive stretch; it is the structural truth of the book, and of a life lived on its own terms—then, now, and beyond. The book lives up to the title song 'Suno Re Kissa,' penned, composed, and sung by Mishra, with others joining the chorus in letter and spirit.

Thodī sī ho gudgudī, thodā sā ho chatpaṭā…

Thode thode ā̃sū ho, par zyādā nā ho aṭpaṭā…

Vaisā vālā kissā agar sunāo tab to jāne jis se,

Yāad rakhe tumko, jānī—okay ye!

I even coined a word for this linguistic conquest: Piyushism. Unlike the artist, the language didn’t resist the label, and I am glad about it. So while Mishra went ‘remembering’, as a reader and translator, I went ‘thinking’ because memories did come, tracing the steps of thought.

A Hindi title for an English translation

A loud statement in itself—because auqaat, like several words threaded through the memoir, resists an acceptable English equivalent, certainly not one that carries that quintessential Mishra-esque charge. The word auqaat becomes a provocation, refusing to be borne in any other way for fear of being lost in translation. It holds class, insult, intimacy, and irony all at once. It was also a way of striking where it hurts most—the emotional weight of being oneself, while giving the stress of invisibility a run for its money, with aplomb.

The opening couplet

An invaluable lesson lies in those four lines that belief often follows action, not the other way around. Mishra encourages taking the first step into the unknown to uncover direction and opportunities. The key is to just go ahead and do it, as he did when he filled out the form for the National School of Drama, sure that he would make the cut and find a place on the list of 20, which he eventually did—a decision that changed the course of his life, and for good.

Life as a relentless quest

His life is an ongoing act of pursuing purpose with passion, shaped by movement, missteps, and moments that only reveal their meaning as we move through them in his blistering memoir. Mishra turns the pages of his life into a fearless artistic reckoning. Through his alter ego Santap Trivedi, also known as Hamlet, he retraces every high and low: the weight of expectations, the intoxication of fame, the chaos of relationships, and the unrelenting pursuit of meaning through art. With dark humour, lyrical rage, and uncompromising honesty, he reveals a man shaped by fire and still burning.

No action is ever wasted

He reiterates that every effort bears fruit in its own time—sooner or later. The journey of Priyakant Sharma, the shy, timid boy who travelled from the bylanes of Gwalior to become the polymath Piyush Mishra, with his fame now soaring across Mumbai’s skyline, bears witness to this belief. The struggle did, eventually, bear fruit, reaffirming that nothing we do is ever in vain. Success is an accumulative act: one lays a brick a day, driven by a fire in the belly—fuelled by what others may dismiss as unattainable, yet remaining a dream that pushes one to the very edge. Much like he has done all this while.

Becoming a better person

His memoir follows a moral arc shaped by action and reckoning. He regrets those he betrayed and forgives those who betrayed him. This clarity came with years of practice and introspection; it was neither easy nor linear. He has lived through emotional chaos and inner conflict, wading through repeated storms to arrive at a place of sanctuary. Easier said than done, certainly, but an inspiring journey worth witnessing, and perhaps, emulating.

Negotiating fear

Fear is an all-encompassing feeling for the protagonist, a constant companion, consuming whatever he drinks and eats; always by his side. Shadowing his very existence, fear has, after all, ruled over everyone. Every character born from a writer’s imagination carries it etched into the heart—so how could Santap, alias Hamlet, remain untouched? But damn, fear haunted Hamlet more than others.

To drive that ‘damn fear’ away, at least temporarily, he was advised to drink alcohol. He, too, wrestled with this dread emotion, only to confront it head-on and, in time, frighten it away. These encounters with fear are depicted in unflinching, unsettling detail. There is no cinematic arc of recovery and no moral crescendo.

Alcohol appears as a companion, crutch, and destroyer, and the language refuses the safety of judgment. His eventual, almost amicable parting with alcohol becomes a quiet but decisive turning point in his story.

Resistance need not be loud to be absolute

Mishra does not seek sympathy or applause. From the first page to the last, he wants attention—unflinching, unsentimental attention. He garners it through his words, which reveal his rage, rhythm, resilience, and rebellion, and continually remind us of his resistance to being bracketed or typecast into a single identity. He reminds us that staying alert—intellectually, creatively, artistically—is a work in progress. Even today, he is constantly reinventing and surprising us with his unique ways of stretching his limits, especially through his indie band Ballimaaraan, named after the famous neighbourhood in Old Delhi. He is often compared to a walking, talking jukebox, with music flowing in and through him, a trait traceable to his early encounter with the harmonium his relative gifted him.

Disillusionment is not failure; it is clarity

Mishra does not romanticise broken ideals, nor does he mourn them. What remains after belief collapses is attentiveness. That attentiveness, I learned, is a form of survival. And it keeps one afloat like Mishra, who didn’t see overnight success in Mumbai, but waited patiently for his turn. He saw failure up close and personal, but didn’t let it define him. He fell prey to addiction but overcame it. He had a debilitating brain stroke, but he conquered it. He found a way where none existed, because he believes in doing.

Distance can act as a form of care

Mishra describes himself as if he were a character on stage—under the spotlight, observed, debated, and sometimes mocked. Writing about himself in the third person allows for a detachment, a deliberate literary strategy rather than a mere stylistic quirk. This unsentimental viewpoint heightens self-critique, making the effort less about self-indulgence. Mishra transforms his lived experiences into a character’s journey, making the memoir read more like a story of failure, survival, anger, hunger, and art than a mere confession. Coming from a deeply performative tradition—such as street theatre, qissagoi, and songwriting—Mishra’s storytelling through the third-person perspective reflects that performative distance.

He repeatedly critiques himself, exposing his vulnerabilities and articulating uncomfortable truths with remarkable honesty—something quite rare. It takes immense courage to undertake this level of self-exposure.

Names carry symbolic, emotional, and thematic weight

The most compelling ethical positions in the book are not declared openly; they are demonstrated through action. Using fictional names in a memoir, especially one as raw and honest as Tumhari Auqaat Kya Hai, is a deliberate ethical and artistic choice that does not compromise truth. The relationships described are emotionally intense and, at times, unflattering, not only to him but also to others. Renaming allows him to tell his truth without exposing real individuals. It is less about anonymity (most readers can probably guess) and more about consent and respect. What matters is not the exact sequence of actions, but how they were experienced—what they did to him, how they shaped him, and how those encounters influenced his growth.

The names he chooses function as archetypes. Santap signifies sorrow, reflecting the child’s inner state after violation, a gloom that sheltered him until he found resonance in another tragic figure, Hamlet, his on-stage persona. Jidda represents the archetypal authoritarian aunt; Sangini embodies longing itself, unreciprocated love that lingers like perfume, unseen yet present. Vishwas, ironically named, signifies betrayal. Jiya becomes the embodiment of his heart and his life.

These names carry symbolic, emotional, and thematic weight beyond the mechanics of autobiography. He does not claim absolute truth about others, only the truth of his perception at that moment. This approach aligns with the literary traditions he comes from—Hindi-Urdu autobiographical writing, theatre, and music—where veiled autobiography is a long-standing practice, revealing the self while deliberately blurring others. Mishra roots himself firmly within this tradition, achieving brutal self-exposure without ethical trespass.

Choosing the battles wisely

To fight for what is right with all one’s might, but one must also protect the light. Gagan Damama Bajyo, the musical play, marked a turning point in his journey: the first real encounter with Mumbai and his debut as a film scriptwriter. Resistance is essential to feeling alive, and resistance did take place in his fight for the screenwriting credits on a film based on this play. He emphasises that resistance that turns bitter corrodes itself. What stays with me most is the insistence on holding on to warmth, humour, and song, even when the world makes it difficult, because by harbouring bitterness towards someone, one only ends up becoming bitter, which defeats the purpose of one’s existence. He tries to find the best in people, and that’s his way of staying afloat, often against the tide.

Meditation as a way of life

An ardent practitioner of Vipassana, he calls it a means to reduce one’s internal struggles because we are all fundamentally affected by two things—excessive attachment and excessive hatred. In other words, craving and aversion, and the most effective way to diminish these issues is to gain control of the breath. It is not a one-time event but an annual cleansing that helps recalibrate thoughts and life, keeping one on track.

Gratitude is an attitude

He expresses it wholeheartedly for all the ‘people around him’. From Rahul Gandhi and Nishant Agarwal, who gave the book its title, to others who were part of his early years in Gwalior and Bhopal, to those the theatre brought him during his Delhi years, and to those he encountered in Mumbai, the book is an ode to his friends, who, as he says, are many. They are his world, his chosen families, who have fed him, housed him, drank with him, fought with him, abandoned him, and rescued him. Many friendships fractured under ego, addiction, jealousy, or ideological differences. But the silver lining remains the enduring friendships forged over the years, including with Ranbir Kapoor, Imtiaz Ali, Hitesh Sonik, and Manu Rishi Chadha (with whom he shared screen space in the recently released Rahu Ketu), among many others. One lasting example is how he made it a point to write, sing and compose the title track for his friend Anurag Kashyap-backed Raam Reddy’s Jugnuma (The Fable), starring friends Manoj Bajpayee and Deepak Dobriyal, last year. That says it all.

Rage needs a creative outlet

When channelled through the right medium, it can create wonders. Piyush Mishra—actor, poet, lyricist, singer, screenwriter, music director, playwright, theatre director, and author—has long lived and worked on his own terms, transforming inner turbulence into an expansive, enduring body of work. More than anyone, it is a story of belief in one’s limitlessness. He can scorch the street, the stage, the screen, and even the pages, and every outing tells the tale of his creative depth and reach.

Self-exposure like no other

He is unflinching about desire, infidelity, and emotional wandering in his memoir. These are not bragged about; they are framed as confusion, hunger, escape, and, at times, self-sabotage. The memoir acknowledges the harm caused—not with moral grandstanding, but with quiet reckoning.

It also shows how love, in difficult times, can look like staying—seeing infidelity, rage, and addiction for what they are and still choosing, each day, to remain. Not out of denial, but out of a steady, considered commitment to what has been built. Priya, the woman he decided to marry one day during their very first meeting, keeps the home standing, even when the ground beneath trembles. She keeps love present, even when it falters. She tends to the flame, not to make it burn brighter, but to keep it from being doused. Perhaps that is why she is called Jiya—not as an emblem of sacrifice, but as a quiet, sustaining pulse of his life, his breath, his heartbeat.

Nothing political about it

The politics of those days make a brief appearance in his memoir, but what stands out is the author’s engagement with communism. It arrived like hope, bringing him intellectual clarity and fostering a sense of community. It gave him the language to articulate injustice and rage. His eventual parting from the ideology is not dramatic; it is quiet, almost weary. In his memoir, he does not settle scores with ideology; instead, he records a deeply personal disillusionment, a man realising that no belief system can replace ethical self-work.

Speaking the unspeakable

Child sexual abuse, one of the most disturbing but significant sections, brought tears to my eyes because I only saw a young child staring through those words. It is quite praiseworthy that Mishra writes about his childhood sexual abuse without melodrama. There is no self-pity, only an acknowledgement of how it distorted intimacy, fear, anger, and self-worth. He links this trauma to later compulsions, addictions, and emotional volatility. It’s written not to shock but to name the wound. Likewise, his relationship with his father is layered and unresolved. He symbolises authority, fear, expectation, and disappointment. Love exists, but it is restrained, complicated, and often silent, which makes it deafeningly loud. However, Mishra neither vilifies nor romanticises his father. The relationship shapes his ideas of masculinity, rebellion, and approval.

End is the beginning in a way

Not all stories need closure. Some are left open-ended. The memoir resists neat endings. Lives continue in fragments, contradictions, and unresolved tensions. Like him, I have learned to stop searching for a resolution, because sometimes going with the emotional flow can unknowingly heal many wounds. Like the characters in his life, who played their roles and then drifted apart. No questions asked and no answers needed because some lives, like some texts, are not meant to be concluded. They are meant to be read—again, and against the grain.

If you're wondering what helped me navigate this challenging stretch of his emotional, intellectual, and creative landscape, it can perhaps best be summarised in Andrei Tarkovsky’s words: “If two people have been able to experience the same thing even once, they will be able to understand each other.” But that is a story for another day—one about synchronicities and the quiet intersections of our lives.