Summary of this article

The narrator believes that Azadi (freedom) is a natural desire for every woman and recalls feeling hopeful and full of possibilities during adolescence.

Her parents’ restrictions gradually silenced her voice, controlled her choices, and made her feel trapped and fearful.

She compares herself to a caged bird, showing how freedom remained a distant dream in her life.

The question ‘What does Azadi mean to you personally’ is something I have ruminated upon several times. The desire to feel liberated and experience Azadi is natural and congenital for every woman—at an emotional level, at a societal level and at a familial level. With this essay, I want to talk about this elusive Azadi and how it has treated me in the past.

As soon as I was old enough to take cognisance of my surroundings—when I was an adolescent, when my intellect and conscience were able to analyse things—I began, with the grace of Allah, to experience some amazing emotions, which was lovely! The scope of objection to anything from anywhere was non-existent. It seemed like the world was my oyster, and I could achieve anything I set my mind to.

These emotions and feelings of wonderment that I was experiencing were something I wanted to share openly with my parents. Unfortunately, they did not share my enthusiasm for a utopian worldview. As a result, despite feeling that I was on top of the world, I ignored the various possibilities that I could have pursued, in terms of what the future had in store for me.

Eventually, silence took over my life, and I got used to being ignored and sidelined by family, by society, by the world at large. It became the norm to live a non-existent existence. Due to restrictions at home, my mind was in a constant state of fear, and I felt helpless. It became imperative to reflect upon when to speak up, when to remain silent, when to keep my eyes lowered, what to wear and what to avoid wearing—so much so that the length and design of the garment, too, was something that was left to my mother’s discretion.

I believe my parents tried to establish who I was as a person through the way I dressed. I remember feeling like a bird trapped inside a cage. Freedom remained a distant dream ...

When I was in Class 8, my friends and I decided to go to the dargah of Makhdoom Sahib after school was over for the day. It is a sacred space in the old town of Srinagar that houses both a dargah and a gurudwara. As we were climbing the hundreds of steps that lead to the dargah, one of my friends, Rukhsana, got tired and sat down. So, we waited for a few minutes till she felt she could resume the journey.

We again started slowly making our way to the dargah. When we reached it, we offered our prayers and expressed our deepest desires, and made our wishes. After the ritual, we began descending the stairs and making our way back. As we were climbing down, I started feel- ing restless. I asked a friend of mine what the time was. She said it was two in the afternoon. I became very anxious, and told them to hurry up and climb down quickly. I was scared that my parents would be furious with me for being so late.

When I eventually reached home, it was, indeed, very late and both my parents were at the door, waiting for me. They were relieved to see me, and asked why I was late. I could not tell them that I had gone to the dargah. Even though I had a valid reason—I had gone to offer prayers—I could not say so. I had to cook up some lies about a classmate borrowing my new pair of shoes to try them out. I told my parents that she had forgotten to return them, and I was scared that Abbu, my father, would be angry because he had bought me the shoes with a lot of love. I told them that I had gone to her home to get the shoes back, and hence got delayed. My parents believed the story, and I exhaled in relief. However, I did feel guilty about lying, and the memory of this incident continues to bother me even now.

To turn my dreams into reality, I had hidden them away in some obscure corner of my heart. Despite restrictions at home, I tried my best to be successful in life. Sometimes, when I wanted to visit a relative or even a friend, I would plead with my parents, convince them in the name of the Almighty, and get them to permit me to venture outdoors. I was not an ill-mannered child; however, I have often wished that I was ... ill-mannered, loud-spoken and irreverent. But by the grace of Allah, there were no restrictions on my studies, or what I was reading, and this made up for the lack of freedom to explore other avenues of life.

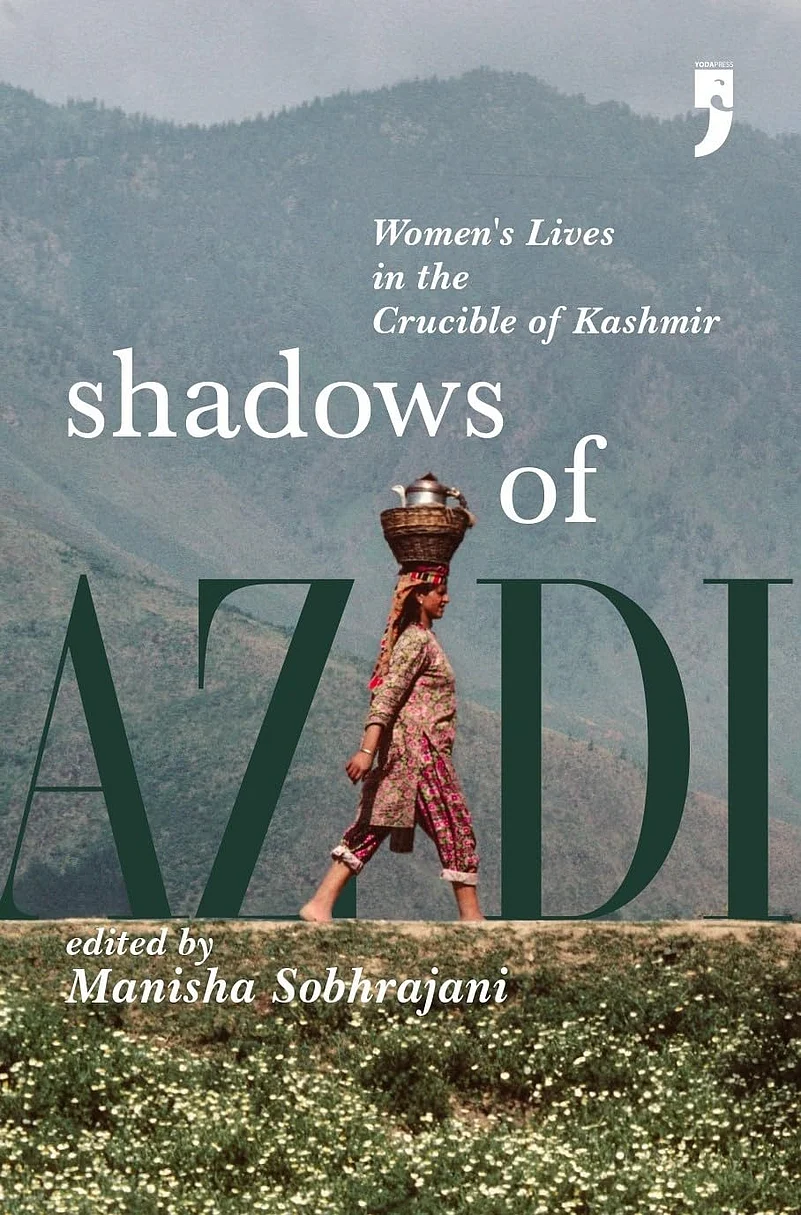

(Excerpted from ‘Shadows of Azadi’, Edited By Manisha Sobhrajani, with permission from Yoda Press)