David Fincher’s The Social Network (2010) completes 15 years on October 1 this year.

The film featured prominent faces like Jesse Eisenberg, Andrew Garfield, Justin Timberlake, Rooney Mara and Dakota Johnson.

This article analyses the aftermath of the AI technological revolution that the film foreshadowed.

Initially, David Fincher’s adaptation of Ben Mezrich’s semi-accurate book The Accidental Billionaires (2009) represented the likeness of a biopic. Although, creative liberties within the scope of the film have built and questioned who “Mark Zuckerberg” really is and continues to do so. In retrospect, The Social Network (2010) didn’t simply aim to map Zuckerberg’s early career, but questioned what could happen in the coming years when ego, technology and cultural anxieties collide with literal human lives at stake. Facebook may have emerged as a platform to connect people, but Fincher’s film underscored the moral ambiguity of its creation—raising questions about data security, identity theft, and the consequences of turning into voyeurs of other people’s online lives.

In 2021, The Wall Street Journal unveiled “The Facebook Files”, with whistleblower documents exposing the unethical and harmful ways the company exploited user data. In 2025, Zuckerberg still insists that The Social Network misrepresents him. The irony endures: an entire film built on the very ‘data’ of his life—creatively altered, without his approval.

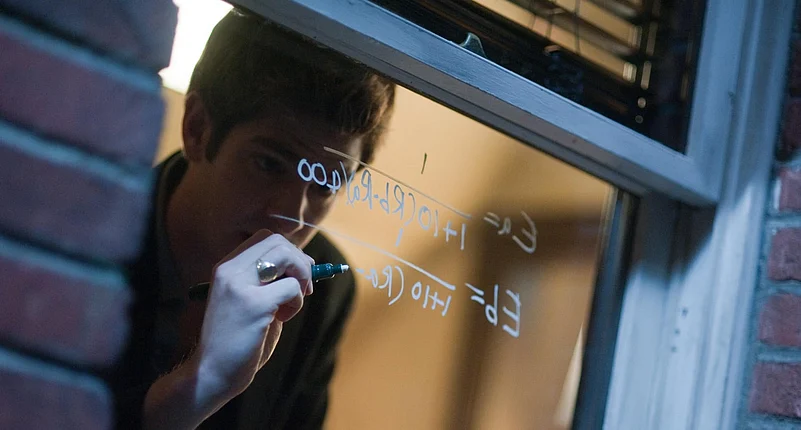

For a vast majority, a rags-to-riches tale is more relatable than watching a boring, grey t-shirt enthusiast coding and scheming his way into billionaire-hood. Fincher’s film turned that assumption on its head with cut-throat pacing, tense dialogues, memorable performances and a fantastic score. Jesse Eisenberg’s take on Zuckerberg—essentially a Sheldon Cooper with an existing sex drive and layered personality—became the film’s defining anchor, even if the real man is far less compelling.

Earlier this year, Eisenberg revealed he has since distanced himself from the character he once played due to who Mark has now become. So what else, if anything, has changed in the last fifteen years?

Well, notably, everything is a number, collected over time and space, to generate more of those numbers to be sold and bought. The reduction of human relationships to data points has commodified the very innocence that once made internet access exciting. The 2000s were a thrilling time to be online, when the internet was summoned through a dial-up connection on landline phones and felt like a place you could actually visit on a family desktop PC. Friends would gather at one house to surf YouTube, chat in chat rooms, and play games together. But as the internet became more ‘mobile,’ the joy of accessibility also became a burden. What began as innocent exchanges of people’s daily lives turned into intellectual property violations pretty soon. Selfies, friendships, votes—they all feed a system that decides what can be sold to whom, who finds who valuable, and one’s worth is in this online economy. Fast forward to 2025, and the moral stakes have escalated from social interactions to the very essence of identity itself.

Despite this film being partly fact; partly fiction, one can’t help but wonder: a site that at its foundation began by rating images of women, taken without consent—could ever ethically turn out well? In an attempt to redeem “nerds,” the protagonist brilliantly exposes how insufferable he truly is. Aaron Sorkin constructed a classic story of what becomes of incel men who are ambitious, but more than that, miserable due to their own follies, even at their best. Although Erika (Rooney Mara) is reportedly a fictional character (as Zuckerberg claims), she functions as a mirror to the public validation-seeking obsession that propels Eisenberg’s character—a stark contrast in a film otherwise populated by women who are either sleeping with the nerds or flailing around cluelessly.

Erika is the only woman in the film with actual agency, refusing to orbit the male ego like everyone else and daring to cut through the performative self-importance of its male characters. She delivers a golden line in the film to Mark that actually stings: “But you’re going to go through life thinking that girls aren’t going to like you because you’re a nerd. And I want you to know from the bottom of my heart that that won’t be true. It’ll be because you’re an asshole.” Ouch.

Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield), Mark’s best friend, gets an invite to a Phoenix party, an emblem of the “cool people” with social capital, instigating a hint of jealousy in him. Mark’s insistence on creating the Facemash website from scratch and sending the invite link to the Phoenix party—post-breakup, drunk, wounded—was a digital power move that said, “I’m smarter than you and I know it.” Sure, the insecure rage helped his innovations but in the long run, internally, Mark’s festering bitterness still anchored his creativity from the driver’s seat. Zuckerberg has condemned the film for misrepresenting his motivations. Yet the film’s perspective eerily mirrors the same internalised rejection, disregard and exploitative vengeance—that his innovations have since inflicted on the masses. The Social Network may play fast and loose with Zuckerberg’s biography, but its lesson is crystal clear: the film doesn’t just critique ambition, it mocks it. It functions as a cautionary tale, exposing how ego, left unchecked, drives brilliance into cruelty, turning ambition into a weapon that wounds the very people closest to you—all in the name of recognition.

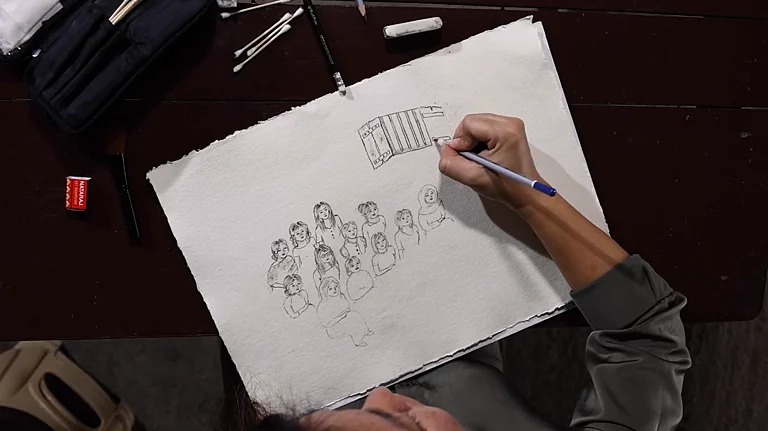

The closing scene of the film lingers like a slow-burning echo: Mark, hollowed by ambition and betrayal, compulsively refreshes his screen after sending Erika a friend request. What began as a spark of inventive brilliance has metastasised into obsession, regret, and loneliness. The audience is left to wonder—was it worth it, the creation, the conquest, the social empire built on fractured alliances and compromised ethics?

Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake), Napster’s founder, showed Mark how to scale Facebook at breakneck speed, favoring ambition over ethics or law. That the one who does it first, is favoured over the one who does it “right”. His advice reads like the blueprint of countless AI ventures today, scraping images, music, and text with little thought for permission, on the pretext of rapid innovation. Rewatching the film brings up a persisting fear that the ethics of data are no longer abstract—they are daily, unavoidable, and dangerously human. AI-bands like “The Velvet Sundown” blew up in 2025 with millions of plays. Tilly Norwood, an AI “actress,” is being signed by numerous agents, sparking outrage over digital doubles practically replacing real artists. Millions of hours of human labour and employment opportunities are digested into algorithms, repackaged like fast food creativity.

Zuckerberg’s early appropriation of personal data wasn’t just opportunistic; it was a quiet redefinition of consent. In the early 2010s, Facebook offered a space to experiment with self-representation. Games and apps encouraged users to craft avatars and cartoonised versions of themselves for profile pictures. With the coming of Vine, TikTok, and Instagram, the act of sharing became almost synonymous with experiencing life: meals 'instagrammed' before being eaten, memories recorded as content and everyday moments turned into short-form skits. Documenting life isn’t new—we’ve done it with journals, photo albums, home videos—but digital platforms made it instantaneous and public. Now, those same uploads often inform AI creations, sometimes with awareness, sometimes without. That same logic creeps into governance, where voter analytics and algorithmic nudges manipulate civic choice.

The Social Network completes fifteen years today and is set to release a timely sequel in 2026 titled The Social Reckoning. The moral friction between innovation and accountability is no longer theoretical—it erupts in courtrooms, social media feeds, and underpins cultural debates about deepfakes, generative art, and the commodification of our digital identities. If the second installment were to trace this trajectory, it should probe the human cost of technological ambition: the subtle and overt ways identity, creativity, and consent are mined and monetised under the guise of progress. At what cost do we let machines know us better than we know ourselves? The Black Mirror Series (2011—) has been doing that task quite successfully, although it would be interesting to see what The Social Reckoning has in store.

Would the sequel interrogate the seductive power of AI, the ethical blind spots of tech visionaries, and the social reckoning we are hurtling towards? Or would it ironically fall into the trap of the same formulaic and algorithmic content fodder that it should question? Only time will tell.