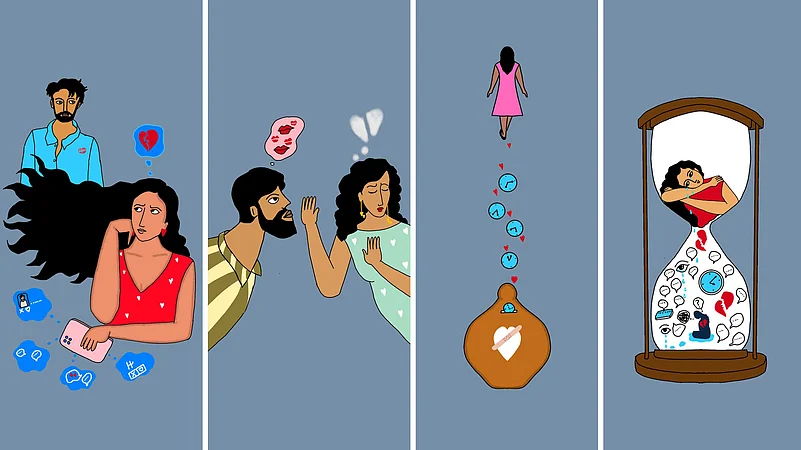

For many women in their 30s, dating is about managing vulnerability, preserving independence and navigating systems that reward avoidance over intention

Many millennial women now find themselves single or unmarried in their 30s and early 40s

Gen Z, meanwhile, appears to be moving in the opposite direction, showing renewed interest in early marriage and long-term commitment

Karan turned up to meet 43-year-old Selina* for a brunch date in a shirt smudged with a lipstick mark. They had circled each other on dating apps for years, never quite swiping right, but when they finally met at a mutual friend’s party, Selina thought it might be worth a try. At the very least, he seemed to tick the basic boxes: early forties like her, gainfully employed, apparently settled.

Then he arrived wearing that shirt.

When Selina pointed it out, he waved it away casually, explaining that he’d been out dancing the night before and the stain must have come from another woman’s lipstick. Selina said nothing. Her mind cancelled him. He either thought she was a fool, was deliberately testing her boundaries, or he simply didn’t care about basic hygiene. None of those possibilities were attractive.

That was the last time she saw him.

For Meera*, the shock came later. She had agreed to a lunch date with a man she met on a dating app. The conversation was polite, uneventful between jobs and families. Nothing that hinted at what would follow. As they stood to leave, he leaned in and kissed her forcefully, without warning or consent.

When Meera pushed him away, he asked whether she had ever been with anyone. When she said she had not been dating, he dismissed her response, refusing to believe her. The incident left her shaken and disillusioned. She was 27 at the time, new on dating apps and recovering from an earlier rejection. She is now 36 and single. “It is tiring to be single in your 30s and trying to date,” she says.

These stories are not unusual. For many women, dating in their 30s and 40s is defined less by romance than by exhaustion, confusion and a sense of emotional attrition.

Mental health professionals say this tension is increasingly visible in therapy rooms. “Across clinical and relationship settings, we see the same pattern,” says Neha Patial, a Delhi-based consultant clinical psychologist. “Women aged 31 to 36 report anxiety, disappointment and fear about the future. The most common question is: ‘What has happened to these men?’”

The Shrinking Pool

Dating does become harder with age. The pool narrows, and the men who remain often come with questions attached. Single men in their early to mid-30s are frequently met with suspicion: are they divorced, emotionally unavailable, or already married and looking for something casual?

There is also the issue of access. In your early 20s, relationships emerge organically through universities, workplaces and large social circles. In your 30s, professional boundaries harden, friendships stabilise, and opportunities to meet new people shrink. Dating apps become the default, and increasingly, the only option.

The men, women encounter on these apps, Patial notes, typically aged 32 to 45, are often financially secure but emotionally unclear. Many are described as commitment-avoidant, keen to maintain youthful lifestyles while still seeking intimacy.

Increasingly, men on dating apps appear to show avoidant attachment patterns. They value independence, fear enmeshment and commitment, Patial explains, and resist taking responsibility for another person’s needs. “Dating apps suit them as a way to meet credible, attractive and interesting women without obligation. While they enjoy connection and companionship, their interest often fades once expectations of commitment arise.”

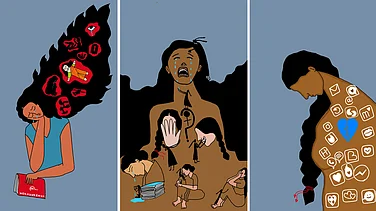

These points are rarely experienced as efficient or empowering. Initial interest often gives way to frustration. Most men who cannot manage basic adult responsibilities, evasiveness around intentions, or conversations that slide quickly into sexual assumptions. Many women describe being viewed in extremes, either as a future wife or a casual encounter, with little room for nuance, curiosity or emotional connection.

Physical needs may be met, but emotional investment remains limited. As expectations shift, interest fades. The result is burnout because of repeated exposure, rejection and emotional depletion.

“They leave the women on the other hand feeling burnt out, emotionally vulnerable, at times rejected often then making the whole dating experience feel traumatic, unfulfilling and a waste of time,” rues Patial.

A Generational Mismatch

For millennials, this exhaustion is also generational. “Many of us rejected our parents’ model of marrying young,” says Rukmini*, 33. “As educated, urban women, we were encouraged to prioritise careers and independence. Marriage was no longer essential.”

That freedom was embraced and with it came certain realisations. Many millennial women now find themselves single or unmarried in their 30s and early 40s. Gen Z, meanwhile, appears to be moving in the opposite direction, showing renewed interest in early marriage and long-term commitment.

Millennials occupy an uncomfortable middle ground: independent, financially stable and emotionally aware, but often unmatched in desire or timing.

That independence shapes how women approach relationships. “I won’t compromise on my autonomy,” says the Bengaluru-based Rukmini. “If a long-distance relationship has no clear plan, I won’t give up my job or financial independence to make it work. That often means walking away after investing time and emotion.”

She does not see this as failure. “It’s a good thing women are no longer compromising at any cost.” Still, doubt creeps in. Are my standards too high? Should I bend more? The real question, she says, is what bending would cost.

Relationship therapist Kasturi Mahanta says this reflects a deeper shift. “Traditional relationship models were built on women’s dependence — financial, social and emotional. That is changing.”

“Over the last 50–60 years, women as a gender group have undergone profound social, financial, and psychological evolution. Our identities are no longer singular or relationship-centric. Meanwhile, many dominant models of masculinity and partnership have remained largely unchanged, or have evolved far more slowly. This creates a relational mismatch,” explains Mahanta.

Today, many women meet those needs independently. Emotional intelligence, shared labour and emotional intimacy are no longer bonuses but non-negotiables. Remaining single, Mahanta says, is often not seen as a failure or a waiting room. “It’s a conscious choice made after repeated disappointment with outdated relational norms and unequal emotional effort. Stability gives women the freedom to opt out of relationships that don’t feel expansive.”

There are multiple factors for women terming dating as emotionally draining, but two stand out consistently, lists Mahanta. “First, misalignment. When someone is repeatedly engaging with partners who don’t share the same intentions, values, or emotional availability, dating becomes performative rather than connective. Second, overstimulation. Dating today often involves rapid pacing, constant availability, frequent rejection, and app-based abundance. When there’s little time to integrate experiences or recover emotionally, exhaustion is inevitable,” she adds.

Many women say they miss companionship more than sex. Sexual needs can be met; emotional connection and shared life-building are harder to find. At the same time, they value the lives they have built: earning their own money, choosing where to live, shaping careers and travelling freely.

They watch friends navigate marriage, children, financial strain and family obligations. Independence brings freedom and isolation. The trade-off is constant.

For Meenakshi, 36, dating is emotionally draining not because of the people she meets, but because of their inconsistency. “It’s not meeting people that’s exhausting,” she says. “It’s the uncertainty.”

She has been on dating apps for nearly a decade. “I joined Hinge in 2017. Since then, it’s been cycles of downloading, deleting and starting again.” She has tried Bumble too, hoping for a better pool. “There wasn’t.” What makes app dating particularly difficult, she says, is how unorganic it feels. “It feels like a part-time job.” Conversations are forced, intentions unclear, and emotional labour begins too early.

Commitment itself feels stigmatised. “If you ask where something is going, it’s seen as pressure,” she says. “I was clear that I wanted a partner, but people still swiped right without wanting the same thing.”

Apps encourage disposability. “A man once told me we could sext today and unmatch tomorrow,” she says. “Nothing is anchored.” There is pressure to impress rather than to be honest—to list restaurants and holidays instead of intentions.

Patial points out that as mental health professionals they see and understand the need to address the loneliness and the real want of having a partner and eventually a family. “So, we help them process these losses and experiences only to somehow,” says Patial, “unfortunately, put the individual back onto the app story again.”

“Dating apps offer abundance, not alignment,” Mahanta adds. “Because abundance is not the same as alignment. Dating apps offer quantity, not necessarily quality. Increased visibility doesn’t automatically translate into meaningful compatibility. That said, dating apps still serve an important function, especially post-COVID. They’re a tool, not a solution. The paradox exists because clarity filters out more than confusion does.

Even prompts feel hollow. “‘Walking on the beach’ is not a simple pleasure if you live in Delhi,” Meenakshi points out. “A simple pleasure should be accessible.” She misses how relationships once formed through friends of friends. “It wasn’t driven by five questions. It was easier, more human.” Her social circle is small, and she knows that limits her chances.

Still, she is not cynical. “I believe in companionship and emotional intimacy,” she says. “I’m just more discerning now. I longer confuse intensity with sincerity.”

In response, many women turn to paid dating platforms in the hope of filtering out non-committal matches, but these often disappoint. “Many women sign up for apps such as Sirf Coffee, Dating Crew and Make My Lagan expecting credible, commitment-oriented profiles. Instead, even after paying, they struggle to get introductions to men who are genuinely seeking stability,” says Patial. “Women are paying to access men who are simply looking for stability. This isn’t something that should be exceptional.” The idea that women are too choosy does not hold up clinically. “What women ask for is basic: respect, clarity, shared values and emotional responsibility. What’s missing is mutual seriousness.”

Some men, buoyed by choice and unconscious power, continue searching for something ‘better’, rejecting viable partners while women are left questioning their worth, points out Patial.

For many women in their 30s, dating is no longer about fairy tales or spontaneity. It is about managing vulnerability, preserving independence and navigating systems that reward avoidance over intention.

Women’s social and emotional evolution has outpaced dominant models of romance. “Women are navigating autonomy, emotional literacy, and self-actualisation, while many partnership scripts still expect compromise, adjustment, or emotional labour from women” Mahanta explains. This creates a mismatch that is often misread as cynicism.

What has disappeared is not romance, she says, but blind optimism. Women are questioning more, articulating needs clearly, and holding on to individuality. “That isn’t bitterness. It’s maturity.” Mahanta started @heymisstherapist online after noticing a persistent gap in how relationships are discussed, with hardly any little thoughtful conversation about what it actually takes to build and sustain healthy relationships.

And so, women keep returning to the apps, with caution, experience and hope. They asking not for perfection, but for honesty, effort and the courage to commit.

*Names changed to protect privacy.

Ashlin Mathew is senior associate editor, Outlook. She is based in Delhi