As the Sri Lankan Air Force plane from Colombo took a sharp turn over the sea to land in Palaly airport, I looked out at the breathtaking view below: turquoise waters glistening in the morning sunlight, a few sailboats lazily skimming the water. There was hope in the air that October morning in 1987. The India-Sri Lanka peace agreement signed in July had temporarily stopped the endless fighting. There was an air of optimism; Sinhalese workers who had fled the fighting trickled back to their old jobs.

Palaly airport brought you to Jaffna, provincial capital of Tamil majority Northern Province—stronghold of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. This was where Tiger chief Prabhakaran, the reclusive leader who operated from Mullaitivu held sway. I had arrived in Colombo about four months ago, just about three years into the profession and was excited to have got an interview with Prabhakaran. The meeting was scheduled for the evening; I had to be at Jaffna University headquarters of the LTTE, from where I would be escorted to a secret location.

I took a broken-down Morris Minor taxi (all cabs were of the ’50s and ’60s vintage) to Jaffna, an hour’s drive from Palaly. The air force controlled air operations but the military, earlier deployed in Jaffna, was now confined to the Dutch fort. The Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) was everywhere in Jaffna, keeping peace and taking stock of weapons surrendered by the LTTE. Prabhakaran had insisted during negotiations that his boys would not hand over arms to the Sri Lankan military. Everyone knew that the Tigers were handing over old, discarded weapons to the IPKF. The Indian army didn’t press the issue.

The drive to Subhash hotel in Jaffna took over an hour; I rattled along at a snail’s pace through the lush green countryside dotted with tall coconut trees.

In Jaffna, news trickled in by early afternoon that the Sri Lankan Navy had stopped an LTTE boat off Point Pedro with 17 Tigers, including some important commanders aboard. The navy said the boat was smuggling arms across the Palk Straits and refused to let off the men, saying the accord did not give immunity for those carrying arms.

Defence Minister Lalith Athulatmudali was told that Pulendran, the man believed responsible for the massacre of a busload of civilians, including Buddhist monks, was among those captured. For the Sinhala Buddhist majority outraged by the atrocity, this was a chance to get even. Lalith insisted that the 17 would be flown to Colombo to face trial for bringing in arms. The Tigers asked the Indians to ensure that the men, held at Palaly airport, are not handed over to Colombo. Rumours began circulating that if the cadres were forcibly taken to Colombo, the orders were to use the cyanide capsule each wore around the neck. They were to die rather than spill out vital information under torture.

Hearing all this, I took a taxi straight back to the airport. Being the only journalist there at that time, it was easy to persuade the IPKF to let me talk to Pulendran.

He looked nothing like a fighter. Wearing a white, half-sleeved shirt over a pair of cotton trousers and rubber chappals, he looked like any other young man in Jaffna. I asked him if he had instructions to kill himself. He said no. It was apparent that Pulendran knew his time was up. But he wistfully recalled that he had been married for just two months and would love to see his wife, to say goodbye to her.

I was shaken by the meeting and got in touch with Yogi, the LTTE political secretary. I asked him if Pulendran’s last wish could be fulfilled. It was impossible, Yogi said. Seeing his wife could weaken his resolve to take the cyanide capsule. But, I argued, the cyanide capsule has been removed when he was captured. Yogi said there were ways to sneak one in.

Negotiations between the LTTE, India, and Sri Lanka continued through the day. By late afternoon, Sri Lankan forces came in to take charge of the men. The LTTE had managed to sneak in the capsule. Pulendra used it and died before he could be flown to Colombo.

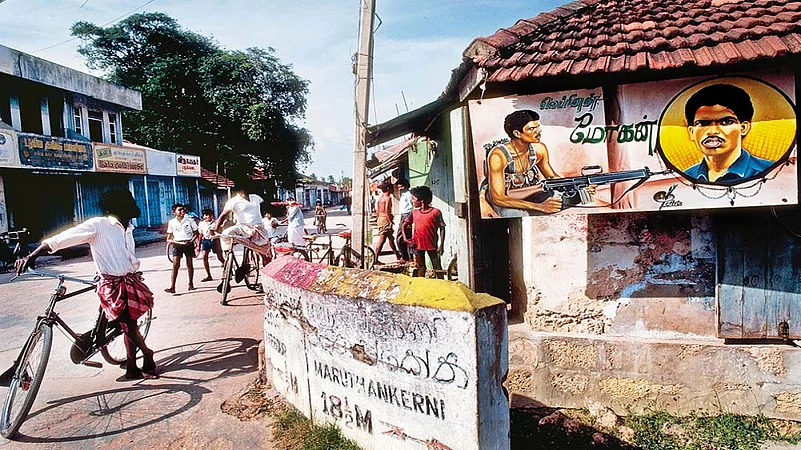

The death of the ‘heroes’ was announced over the public address system in Jaffna. People with grim faces gathered in street corners. An air of despondency hung over the town. I stepped out at dusk to go to Jaffna University, where the LTTE had an office.

Outside, Jaffna was like a war zone. Tiger cadres, who till then had refrained from displaying weapons, were out in strength, brandishing AK-47s. Motor bikes carrying armed LTTE men sped by frenetically. Shops downed their shutters; there was not a taxi in sight. I got one willing to drop me, but was told I had to find my way back to the hotel.

The LTTE office was manned by young boys in battle fatigues carrying assault rifles. I waited for Yogi. He walked in around 10:30 pm and gave me the bad news: my interview has been scrapped. He bitterly complained that New Delhi had not bothered to exert enough influence on Jayawardene and Athulathmudali to save Pulendra and his companions. Around 11: 45 pm, Yogi and three other cadres escorted me back to the hotel.

As soon as I entered, I was told that the owner wanted to see me urgently. The elderly Tamil gentleman had an urgent request. He said he had five Sinhalese staff-members, whose lives were in danger. He wanted me to take them to the IPKF camp for safety. At 4:30 am, he would have a car waiting for me.

I was told that the very same Yogi had stormed in around 8 pm, demanding that the Sinhalese workers be handed over. They had been sent for safety to the owner’s home.

I woke up to a dreadful sight. At the bus stop next to our hotel lay the bodies of 10 Lankan soldiers who were held prisoner by the Tigers before the peace pact was signed. They were shot in cold blood; their bodies bore marks of torture. The Sinhalese manager of a cement plan was similarly shot.

The Sinhalese waiters were petrified; I was trembling with shock. They crouched at the back of the van that was plastered with press stickers. We reached Jaffna fort, which was occupied by the IPKF, with a small detachment of the Lankan army. I called the Colonel and said that I wished him to shelter the five workers.

His immediate reaction: “Please don’t bring the Sinhalese here. I don’t want them. It is your problem. I cannot take charge of these chaps.” Fuming, I went to the Lankan camp and made the same request. They happily agreed and promised that they would be sent back to Colombo. As I came away, I realised I did not even know the names of the Sinhala boys.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Fright Nights")

ALSO READ