Summary of this article

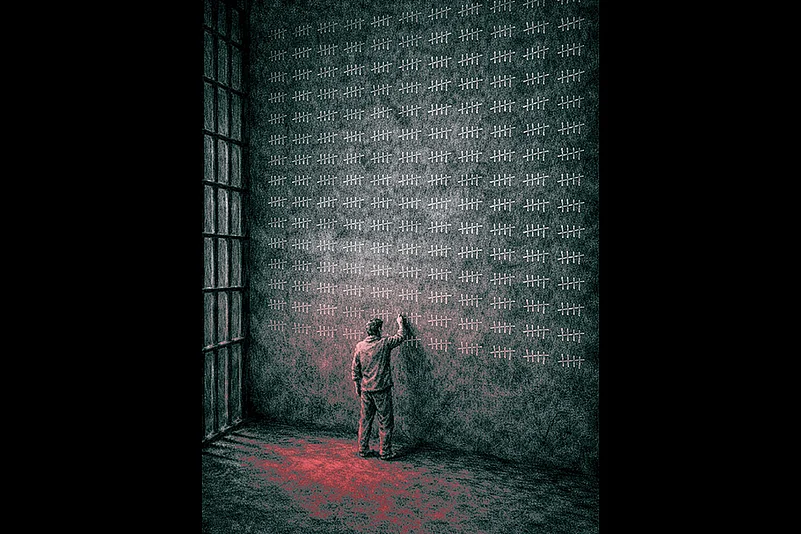

Twelve men were wrongly convicted in the 2006 train blasts; five spent nearly ten years in solitary confinement on death row before all were acquitted in 2025.

Prison authorities ignored legal distinctions, enforcing isolation, denying work and reading material, and treating all death row inmates as definitively guilty.

Prolonged incarceration caused severe psychological harm, suicides, and death, including Kamal Ansari’s death in custody, leaving lasting damage despite eventual acquittal.

“Every prisoner is a world of one.”

—Ehtesham Siddiqui and Asif Khan’s decade long death row experiences

On September 30, 2015, a Mumbai city court sentenced five men to death and seven to life imprisonment for their role in the suburban train blasts of July 2006. Given the political nature of the case, the judgement had an immediate impact on the lives of the 12 men. Designated as convicts, all were transferred from the Mumbai Central Jail at Arthur Road to different prisons in Maharashtra. Three were lodged in the Phansi Yard of the Nagpur Central Jail and two in the Phansi Yard at Pune’s Yerawada Central Jail. In April 2021, one of them, Kamal Ahmed Ansari, died in a city hospital in Nagpur because of COVID. Invisible and forgotten by the outside world, the fate of all 12 men, including the deceased Ansari, was finally decided in July 2025 when a divisional bench of the Bombay High Court pronounced them as ‘not guilty’.

The impact of the judgement is far-reaching as it raises fundamental questions about police investigations, custodial torture, malicious prosecutions and the compromised nature of terror trials. But what remains outside the purview of the judgement is the decade-long imprisonment that the 12 men endured. Within this, the death row punishment that five suffered amid the horrors of the punishment site merits discussion because the procedural confirmation of their death sentence did not happen for 10 years and yet they were kept in solitary cells in Phansi Yards.

It needs to be noted that the 10-year solitary confinements at the Phansi Yards were over and above the custodial violence that all 13 men, including Abdul Wahid Shaikh who was acquitted in 2015, suffered at the hands of the police and jail staff prior to the lower court verdict. Within this context of repeated violence and wrongful solitary confinements, the death of Kamal Ansari and the living experiences of Ehtesham Siddiqui, Asif Bashir Khan, Naveed Husain Khan, and Faisal Shaikh enhance our understanding of the challenges that political prisoners encounter in their struggles against vengeful punishments.

The experiential accounts of Ehtesham Siddiqui and Asif Khan, provided through written and oral interviews, reveal their decade long struggles for hope, sanity and freedom in the hopeless, insane and unfree world of the Phansi Yard. Their interviews substantiate how the death row intensifies the structured brutalities of the penal system and remind why the struggle against the death penalty must also include the fact of prison violence.

The Two Testimonies

“From October 2015 to July 2025, I was held in the “Phansi Yard” (renamed the Security Zone in 2017) of Nagpur Central Prison. The yard, split into Yard A and Yard B, contained 30 cells in total. In these yards, every prisoner is a world of one; we are kept in separate cells. While we were permitted to socialise within the yard for eight hours a day—from 7:00 AM to 12:00 PM and 3:00 PM to 6:00 PM—the remaining 16 hours were spent in total solitude.”

On entering Nagpur prison, Ehtesham Siddiqui needed to confirm his identity as a convicted prisoner on death row. Armed with the Sunil Batra judgement [Sunil Batra vs Delhi Administration, 1978], Siddiqui argued that the category ‘prisoner under sentence of death’ was inapplicable as the sentence had not been confirmed by the High Court. While the authorities conceded the argument and allowed him and his co-accused to not wear the convict uniform, the fact of solitary confinement at the Phansi Yard and denial of work remained non-negotiable. Entering the yard within months of Yakub Memon’s hanging was difficult as Siddiqui writes, “Yakub was remembered for his exemplary behaviour. To me, his death was a haunting reminder of a systemic failure: the harrowing thought that while the truly guilty might walk free, the innocent can be sent to the gallows.” Siddiqui was an exception because at the Phansi Yard, the question of innocence and guilt is irrelevant because the prison authorities refuse to differentiate between ‘prisoners under sentence of death’ and those whose cases are still in process, a point clarified in Asif Khan’s case.

Disturbed by the punishment order, Asif Khan desperately wanted to read the judgement when he entered Yerawada prison. However, in cue with the official order, Khan and his co-accused were kept waiting at the prison gate for several hours. During the strip search, the staff confiscated his copy of the judgement and summarily locked the duo in solitary cells in different wings of the Phansi Yard. No questions were answered. Khan retrieved the copy with difficulty as he could only appeal to the Superintendent on his weekly rounds. When he wanted a personal copy of the daily newspaper and offered to pay for it, he was denied. He had to wait for a whole year to get it. The experiences showed that death row prisoners have no personal rights and are compelled to endlessly wait, beseech and plead. Worse, since the staff believes that the ‘truly low’, not only morally but economically and socially too, are fit subjects of the death row, Khan’s show of payment deserved a suitable lesson.

Outside of the lordly power that the staff wields over convicts who are overwhelmingly rapists and murderers from impoverished or marginalised backgrounds, there is an added reason for the impunity at the Yard. Based on his long incarceration in different prisons, Khan believes that the staff’s extra vengefulness and intimidatory attitude arises because of the Yard’s secluded location and because death row prisoners have fewer legal rights. As he says, in the eyes of the staff, all convicts are guilty and they deserve to die.

Consequently, for unlettered prisoners who remain unaware of the sentencing process, the quotidian reality of Phansi Yard is most oppressive. Khan gives the example of a yard mate, a rape accused, who became mentally disturbed and manifested distressing symptoms. Timely help from other inmates, including from the counsellor on round, aided his recovery. Because Khan helped the yard mate in his legal case, the sentencing was heard and the High Court acquitted him on the grounds that the prosecution had failed to establish its case. However, each instance of mental instability doesn’t necessarily end in acquittal. Khan’s cell neighbour committed suicide by using the towel to hang himself from the bars of the door. Convicted in a well-known 2016 rape and murder case, Jitendra Shinde, an impoverished Dalit, was sentenced to death along with two co-accused in 2017. However, the confirmation was transferred to Mumbai, and it remained pending till the time of his suicide in 2023.

One of the ironic features of the modern prison system is its reliance on the law of arbitrariness and the death row is no exception.

For Khan, the incident was shocking as Shinde had tried to hang himself days before. The matter was raised with the jail authorities, but they barely intervened, including the counsellor. The fact that Shinde succeeded in his second attempt proved that the practice of constant vigil was farcical. While Siddiqui and Khan were subjected to nightmarish surveillance, a rapist cum murderer with clear evidence of mental ailment was not watched. Was it that ‘Muslim terrorists’ needed monitoring, but a lowly Dalit whose repulsive crime which breached caste hierarchies, deserved to die? Six months after the death, Shinde’s mother, petitioned the court for a court monitored inquiry into the death as it was apparent that Shinde was suffering from serious mental health issues which the authorities never heeded. Almost two years have elapsed, and nothing has been reported on the matter.

Not surprisingly, anguish engulfs the lives of who remain locked in for hours on end without a bed or a fan in a “concrete box”, which can be either 10 feet wide and long or even smaller, as Siddiqui describes his cell. With a tiny wire mesh window along with a half-exposed toilet, most convicts are reduced to a state of desperation or resignation. Many spend their time, Siddiqui says, in a “haze of television, radio, or board games like carrom and chess” and take sleeping pills immediately after dinner, in a “desperate attempt to fast-forward through their reality”. Siddiqui found “a profound, soul-crushing hopelessness in many; they eventually stopped dreaming of exoneration and simply prayed for a life sentence—viewing a lifetime behind bars as a “mercy” compared to the yard.” The “psychological weight of a looming death sentence” was unbearable.

The death row exemplifies the meaning of, ‘living death’, and Siddiqui astutely points out that the “The death row environment is designed for stagnation; it is meant to still the soul before it stills the heart”. But what are the ways of not stagnating or losing one’s imagination? Khan said that much of his time in the initial years was spent over the judgement via letters to his lawyers. When he was allowed out of his cell, he mixed with his yard mates and assisted them in their legal cases, via his lawyers and others who were associated with the then Delhi-based legal aid research centre, Project 39A. For the rest, it was his faith that helped him endure.

Siddiqui’s fight against anguish and round the clock surveillance was a solitary one. In a diminishing world paradoxically defined by a “total loss of privacy” amid solitude and loneliness, he had to keep his “mind moving forward while [his] body was trapped in a 10-by-8-foot box”. His most “precious resource” was the electric light as it allowed him to read undisturbed. In his own words, he “transformed his cell into a personal library” and he read “approximately 1,800 books from the prison library”. He says, “I refused to let my mind atrophy.” Finally, it was faith that helped. As he says, “Faith was my only source of light in an environment defined by darkness. It provided hope when logic suggested despair… In the shadow of the gallows, faith becomes the only thing the state cannot take from you.”

In Others’ Words

One of the ironic features of the modern prison system is its reliance on the law of arbitrariness and the death row is no exception. Invented in the colonial era as a sequestered block within a panopticon layout, the death row in postcolonial times is multifunctional, and most manuals have renamed this last port before the gallows as “Security Zone” or “Special Yard”. Consequently, the death row often doubles up as a security barrack for the undertrials who the prison authorities think need to be isolated from others. Hence, Sudha Bharadwaj’s account is entitled From Phansi Yard and Varavara Rao’s undertrial account (in the BK-16 case) is also about the Phansi Yard in the men’s prison at Yerawada. Additionally, the Yard can be used for punishing recalcitrant undertrial prisoners, such as Arun Ferreira who was lodged for over a year and more after he participated in a prison strike in 2008 in Nagpur.

In his memoir, Colours of the Cage (2014), Ferreira mentions the transfer of three undertrials accused in the Mumbai train blasts case (who were subsequently given life sentences in 2015) to the Phansi Yard after they “had been thrashed by the prison authorities in Mumbai”. They “arrived with multiple fractures and bruises” (70). The 2008 incident at Arthur Road prison was a gory one as the staff inhumanly beat 40 prisoners during a controversial jail transfer under the supervision of the Superintendent. Based on petitions filed on behalf of prisoners, the matter reached the High Court which directed an inquiry and concluded that “the force was used disproportionately and also for the reasons extraneous”. The court directed the jail authorities to transfer back the prisoners as the said transfer was illegal.

Such concentrated savagery, Varavara Rao explains, arises from the prison staff’s self-perception of inferiority compared to the regular police. Despite the nomenclature and uniform, the prison staff lacks the untrammelled powers of the police, and Rao says that the self-perceived “inferiority leads them [prison staff] to see the inmates as criminals, and given their uniforms, it is all the more humiliating. So they become perverse, cynical and sadist—as the state expects them to”. At the Phansi Yard, Rao witnessed a sadistic beating that a death-row convict suffered at the hands of the jailor for committing a habitual prison offence, of burning newspapers for making tea. Rao observes that catching the convict in a clandestine activity was opportune for the jailor who had been waiting to take revenge as the convict had earlier questioned him over the lack of mutton dishes in the jail canteen. The assault over the tea was really a case of delayed punishment for the earlier act of defiance.

Rao’s psychological explanation strengthens what we already know: how the penal system authenticates and replicates existing social relations between the ruler and the ruled. As a form of power, penal sadism enhances the entrenched forms of societal violence through brutalisation of prisoners based on their offence as well as on their caste, class, gender or religious identities. That prisoners also initiate violence only proves that as an institution of the public justice system, prison violence questions the fundamental purpose of correction or reform.

This process of dehumanisation is most extreme at the death row as it epitomises societal antipathy towards criminals who deserve exemplary or highest punishments because of their morally shocking crimes. Undoubtedly, the legal order which pronounces such punishments safeguards society through normative values of justice. However, as the life accounts from the death row show, the debate over death penalty cannot be restricted to questions of the justness of death as a punishment versus the sanctity of life, or about the necessity of deterrence versus its lack, or about just rareness versus erroneousness of judicial decisions. What needs recognition is that the legislated punishment of death does not occur in vacuum; it is structured through the dehumanising and violent prison system. Besides the ethical, social and legislative aspects, the question of death penalty must take cognisance of the violence generated within the penal system and of the need to build accountability for its persistence. Those who survive the death row return to tell us of their struggles for hope and justice. Additionally, Siddiqui and Khan’s testimonies show the admirable resistant strategies that they individually built for surviving 10 years in the Phansi Yard. Most importantly, these singular testimonies strengthen the collective history of political prisoners and recall the resistant struggles that 13 men waged for nine long years as undertrial prisoners in the Mumbai train blast case.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Sharmila Purkayastha is an independent researcher based in Delhi. She has authored Of Captivity And Resistance: Women Political Prisoners In Postcolonial India (2023)

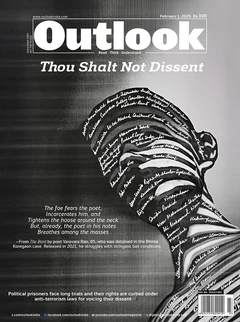

This article is part of the Magazine issue titled Thou Shalt Not Dissent dated February 1, 2026, on political prisoners facing long trials and the curbing of their rights under anti-terrorism laws for voicing their dissent.