Summary of this article

Ahead of Budget 2026, gig workers are demanding constitutional guarantees, fair wages, and a national social security framework as income insecurity and long work hours deepen.

The Economic Survey flags low earnings, algorithmic control, and lack of credit access, reinforcing workers’ claims of precarity despite the sector’s rapid growth.

Outlook spoke with gig workers, MP Manoj Jha, and director Nandita Das to understand the demands and ground realities of life as a gig worker.

As the Union Budget approaches on February 1, all industrial sectors, segments, and the general public are waiting with bated breath to see what gifts and good news (or not so good news) await their financial future.

India’s gig worker sector, estimated to be around 7.7 lakh according to a 2023 NITI Aayog report, is also hoping big. The gig work sector has been in the spotlight on and off since December, with protests on the ground, dismissal of demands from top leadership of the platforms which employ them, and even a small hopeful message from the labour ministry.

But the ground reality is this, no fixed income, unrealistic work hours, no workers safety as promised in other sectors, and lots more. All these issues were highlighted on Friday at a Janpahal and Gig Workers Association-led report screening at New Delhi.

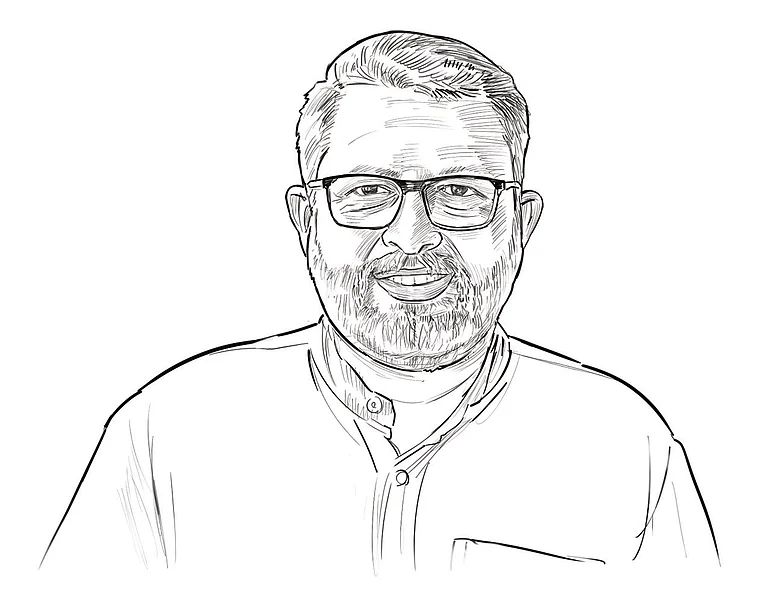

Rajya Sabha MP Manoj Jha has argued that while states such as Karnataka have taken the lead in regulating platform work, lasting protection for gig workers requires strong central intervention.

Jha, one of the panelists at this event and one of most vocal supporters of gig workers' rights, spoke with Outlook after the event.

“States can do a lot, have their own bills and laws, but any programme, any legislation for social security is much more robust and all-encompassing if the central government intervenes,” Jha said. “If the central government develops enabling legislation and develops a particular funding pattern for the states — where revenue deficit is there or they don’t have surplus — I think the initiative should come from the central government.”

Jha linked the issue directly to the constitutional vision of economic justice, insisting that the Union Budget must be viewed through the lens of Article 39 of the Indian Constitution, which directs the State to ensure adequate livelihoods and equitable distribution of resources.

On his expectations from Union Budget 2026, Jha claims he has always been a proponent of the central budget addressing the gig worker economy.

“If there is any problem with gig workers, the budget should be seen through the prism of Article 39,” he said. “They are miles away from Article 39. And until that distance is not over, we will sit in the Constitution Club and talk about gig workers or some other working class,” he adds, as the press meet was also at the Constitution Club.

He took a shot at the recent statement by the Chief Justice of India during a minimum wage demanding petition that ‘unions have been destroying India’s economic growth, and called them ‘jhanda unions’. Jha, from the podium, expressed concern at this observation and said, “Me or Raghav (Chadha) or Rahul (Gandhi) can sit outside parliament and protest for these workers and that would be personal sensitisation. But when there is systemic desensitisation, when there is institutional insensitivity, what can we hope for?”

Economic Survey Flags Falling Incomes, Workers Cry Algorithmic Control

The concerns raised by Jha find strong backing in the Economic Survey 2025–26, which underlined the precarious nature of gig work despite the sector’s rapid expansion. According to the Survey, about 40% of gig workers in India earn below ₹15,000 per month, highlighting widespread income insecurity. Apart from the government’s survey, the report presented by GiGWA and Janpahal claimed over 30% of the surveyed gig workers worked around 70 hours per week, well above the 40-hour average under current labour laws.

Coming back to Economic Survey 2026, it called for “significant policy interventions,” and recommended the introduction of minimum per-hour or per-task earnings, including compensation for waiting time, to ensure fair wages and reduce the widening cost disparity between regular and gig employment. Notably, this demand was one of the primary driving forces behind the gig workers protest of December 31-January 1, apart from ban on ten-minute deliveries and more.

The survey stressed that the objective of gig-economy policy should be to allow workers to exercise “genuine choice” rather than being pushed into platform work due to weak job demand, skill mismatches, or the absence of a safety net.

Income volatility, the Survey noted, also restricts gig workers’ access to credit. Financial inclusion remains limited, with most workers relying on “thin-file” credit options, making them vulnerable to debt traps. The report further flagged the growing power of platform algorithms, which control work allocation, performance monitoring, wages, and supply-demand matching.

This finds backing in the report presented by the workers. The rating system is the bane of their existence, said Nandita Das, director of Zwigato and a panel member at the event. While Jha said, “Let’s think of Marx for a moment. The factory bell has been replaced by the app alarm. The factory gates are the apps, and the supervisor is the invisible algorithm. The labourer is still trapped, only much worse now.”

Workers Seek Immediate Relief In Budget

From the workers’ side, expectations from the Budget are modest but urgent. Nitesh Das, Organising Secretary of the Gig Workers’ Association, said there is little optimism about a sweeping policy announcement, but unions are pushing for targeted measures that can stabilise livelihoods.

“The most important thing we wanted was that there should be something like PM SVANidhi,” Das said, referring to the central scheme that offers collateral-free loans to street vendors. “These workers can get a small loan so that they can get support in the long run.”

Describing gig work as inherently unstable, Nitesh Das pointed to frequent platform switching and declining wages. “This is very dilute work. Workers are shifting to different platforms. But money, wages are an important factor,” he said. “Throughout the years, wages have gone down, and we are seeing a lot of issues happening from the wages perspective.”

According to Das, access to small, low-interest loans could provide a crucial buffer. “These small loans can help the workers to maintain their livelihood in a good way. This is something we look forward to in this budget, if it comes up,” he said.

‘Is The City Ready To Be A Workplace?’

Beyond wages and credit, Nitesh Das said policymakers have failed to acknowledge the spatial realities of gig work. “The city is a workplace for the workers,” he said. “The most important question that comes to us is whether the city is ready for the gig workers as a workplace.”

Issues such as road safety, climate exposure, lack of resting spaces, toilets, and drinking water are routinely ignored, he added. “The basic amenities that the workers are asking for — I don’t know how they can enter through this sphere,” Das said. “But something which maintains and provides the city as a workplace concept for the gig workers, that would be a great help.”

Pooja, a delivery ‘partner’ for Swiggy now, came with her toddler. “I take him everywhere, even for deliveries.” As she tried to speak, the child, being a child, had a tantrum and she had to rush to manage him. Nandita Das commented, “this is a live example of working women. We have to always manage everything at once, and our burden is always doubled.” With the child satiated with the promise of noodles later, Pooja (while not calling it a budget expectation) said she wishes government acknowledges the challenges of women gig workers. “Offices have toilets, you know. We don’t,” (commenting on badly maintained public toilets). “And periods, when we get periods, it is so much more impossible for us. We drive 12 hours shifts. When do we change? Where? We need reasonable work hours, reasonable pay, and no threats.”

Karnataka Model And The Missing National Framework

One model frequently cited in the debate is the Karnataka Platform-Based Gig Workers (Social Security and Welfare) Act, 2025, which mandates a 1–1.5% welfare fee on aggregators such as Zomato, Uber, and Porter to fund social security, insurance, and health benefits. The law also establishes a 16-member Welfare Board to oversee registration, compliance, and grievance redressal, and guarantees transparency in automated decision-making and a 14-day notice period for termination.

While the Karnataka law has been widely welcomed by unions, its state-specific nature underscores the absence of a comprehensive national framework — a gap that MP Manoj Jha and others argue must be filled by the Centre.

Unimplemented Code On Social Security

A key expectation of gig workers ahead of the Budget is progress on the Code on Social Security, 2020, which for the first time formally recognises gig and platform workers and allows the government to frame schemes covering life, disability, health, maternity, and old-age benefits. Although the Code consolidates nine labour laws and promises universal social protection through mandatory registration and digital compliance, it remains largely unimplemented.

For gig workers, unions say, the challenge is no longer about recognition on paper but about translating legal intent into enforceable rights.

Pooja adds, “I drive till 12 AM, why? To get incentives. The incentive is Rs 300; our daily petrol is 200. I want the government to do something for us, anything. Be it ensuring the platforms give us water to drink, or a place where we have a safe toilet. Anything, just something.”