Summary of this article

According to sources, the Home Ministry is discussing whether rules mandating standing or observance should apply to national song as well

At present, there is no legal requirement compelling citizens to stand for or sing the national song.

Modi government’s decision to foreground the 150th anniversary just ahead of elections in West Bengal is revealing.

A spectacular cultural display unfolded along Kartavya Path in the heart of the capital during the 77th Republic Day celebrations, with around 2,500 artists performing a choreographed dance to Vande Mataram. The performance was the centrepiece of this year’s parade, marking 150 years of the song’s composition.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi watched as dancers showcased folk and classical forms from across the country in what was presented as a tribute to the enduring legacy of Vande Mataram, written by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay in 1875 and later accorded the status of national song.

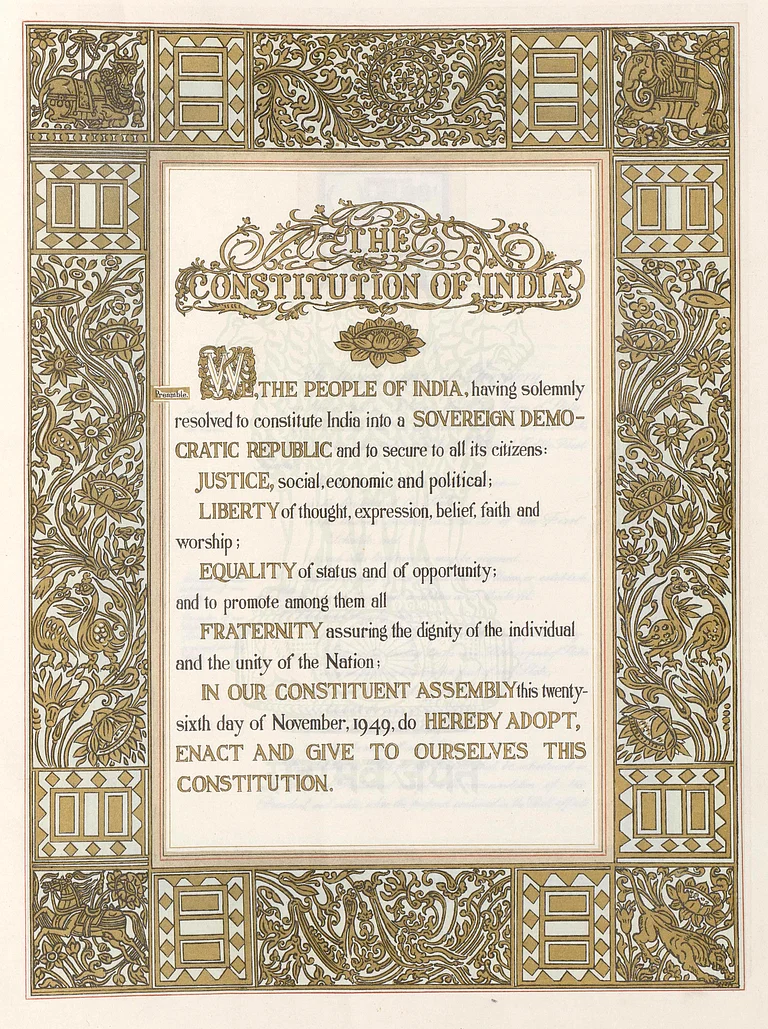

The Sanskrit phrase “Vande Mataram” translates as “I bow to thee, Mother”. Written as a hymn and included in Bankim’s novel Anandamath, it weaves together nationalism, devotion, spirituality and identity. During the freedom struggle, it became a rallying cry against colonial rule and acquired an emotional charge that still resonates.

But the song has never been politically or culturally neutral.

Protocol, Power and Compulsion

As part of the 150th anniversary commemorations, the Union government is reportedly considering whether Vande Mataram should be accorded the same protocol as the national anthem Jana Gana Mana. According to sources, the Home Ministry is discussing whether rules mandating standing or observance should apply to the national song as well. No formal decision has been announced so far.

At present, the Prevention of Insults to National Honour Act, 1971 applies only to the national anthem. Even Article 51(A) of the Constitution mandates respect for the anthem, not Vande Mataram. There is no legal requirement compelling citizens to stand for or sing the national song.

The possibility of extending such protocols raises a familiar concern: the use of cultural symbols to enforce conformity rather than encourage shared respect.

Why Vande Mataram Works for the BJP

There is a clear political logic behind the ruling party’s embrace of Vande Mataram. With its evocative imagery of the motherland, the poem provides a framework for advancing a Hindu nationalist imagination of India.

In a country as diverse as India, where identities fracture along lines of caste, religion and region, the BJP seeks to project the song as a unifying force. When Prime Minister Modi reaffirmed it in Parliament, it was not merely an act of homage. It was a political gesture aimed at consolidating a collective Hindu identity and positioning the BJP as the custodian of a cultural renaissance.

This choice is also telling in who is not foregrounded. Figures such as Raja Ram Mohan Roy or Rabindranath Tagore — whose life’s work centred on rationality, social reform, gender equality and universal humanism — do not fit comfortably within the ideological frame of Hindutva. Tagore’s nationalism was nuanced and inclusive, resistant to rigid identities.

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s nationalism, by contrast, is often interpreted through a more exclusivist lens. That makes him more compatible with the BJP’s preferred narrative of India as a Hindu civilisational state. Elevating Bankim is not accidental; it helps forge a historical lineage that aligns with contemporary political goals.

The Uncomfortable History

What the ruling party appears comfortable with is the problematic legacy embedded in Anandamath. According to writer Ziya Us Salam Bankim referred to Muslims in the novel as “bearded degenerates” and portrayed them as enemies, despite the Sanyasi Rebellion — on which the book was loosely based — involving Hindu and Muslim participation.

Through the character Jnanananda, the novel contains passages that openly call for violence against Muslims and the “purification” of the land. These are not incidental lines; they reflect a worldview that casts Muslims as outsiders to the nation.

That such aspects do not trouble the BJP is unsurprising. Cultural nationalism under the Modi government has repeatedly been deployed as an electoral language when political arithmetic becomes difficult.

A Stick to Beat Muslims With?

The controversy around Vande Mataram is neither recent nor manufactured. From the early 20th century, sections of Indian Muslims objected to certain verses of the song because of their religious imagery, even as many Muslims participated in the freedom struggle where the song was sung. This tension is well documented and remains unresolved.

The first two verses of Vande Mataram make abstract references to the mother and the motherland, without religious connotation. However, later verses explicitly invoke Hindu goddesses.

The third stanza, as published in Anandamath, reads:

Thou art Goddess Durga, Lady and Queen,

With her hands that strike and her swords of sheen,

Thou art Goddess Kamala (Lakshmi)… and Goddess Vani (Saraswati).

This is precisely why the founders of the Republic chose to limit official use to the first two verses. The discomfort was acknowledged, not denied.

Yet today, the song is repeatedly weaponised against Muslims, portrayed as a test of loyalty, despite their objection being theological rather than national. It becomes a stick to beat a minority with, not a bridge to unity.

Bengal and the Politics of Timing

Seen in this light, the Modi government’s decision to foreground the 150th anniversary just ahead of elections in West Bengal is revealing.

The song was written by a Bengali icon. Invoking Vande Mataram in Bengal is not abstract nationalism; it is an attempt to claim cultural ownership in a state where the BJP has historically struggled to establish roots.

Polarisation here is not an unintended consequence. It is a political tool. By projecting a sanitised, one-dimensional version of history, the government sidelines complexity and dissent in favour of ideological clarity.

Governments mark anniversaries all the time. But choosing to do so loudly, ceremonially and politically on the eve of a high-stakes election suggests design, not coincidence. As many commentators noted during the last Bengal elections, even Prime Minister Modi’s cultivated resemblance to Tagore ( PM Modi let his beard grow) became part of this symbolic contest.

This, ultimately, is not about a song. It is about how history is repurposed — and who it is meant to include, and exclude.