Summary of this article

India’s Republic was shaped by a long constitutional journey, from the 1929 call for Purna Swaraj and the first Independence Day on January 26, 1930, to the adoption of the Constitution

Foundational debates on equality, federalism and the balance of power between the Centre and the states reflected deep anxieties after Independence.

It produced a Constitution that envisioned a strong Centre while warning against over-centralisation.

Every year, as Republic Day passes, the country is swept up in familiar scenes of celebration: patriotic songs blare from radios, billboards shift to the tricolour, television channels air films steeped in nationalism, and schoolchildren return from Republic Day functions with hands full of ladoos.

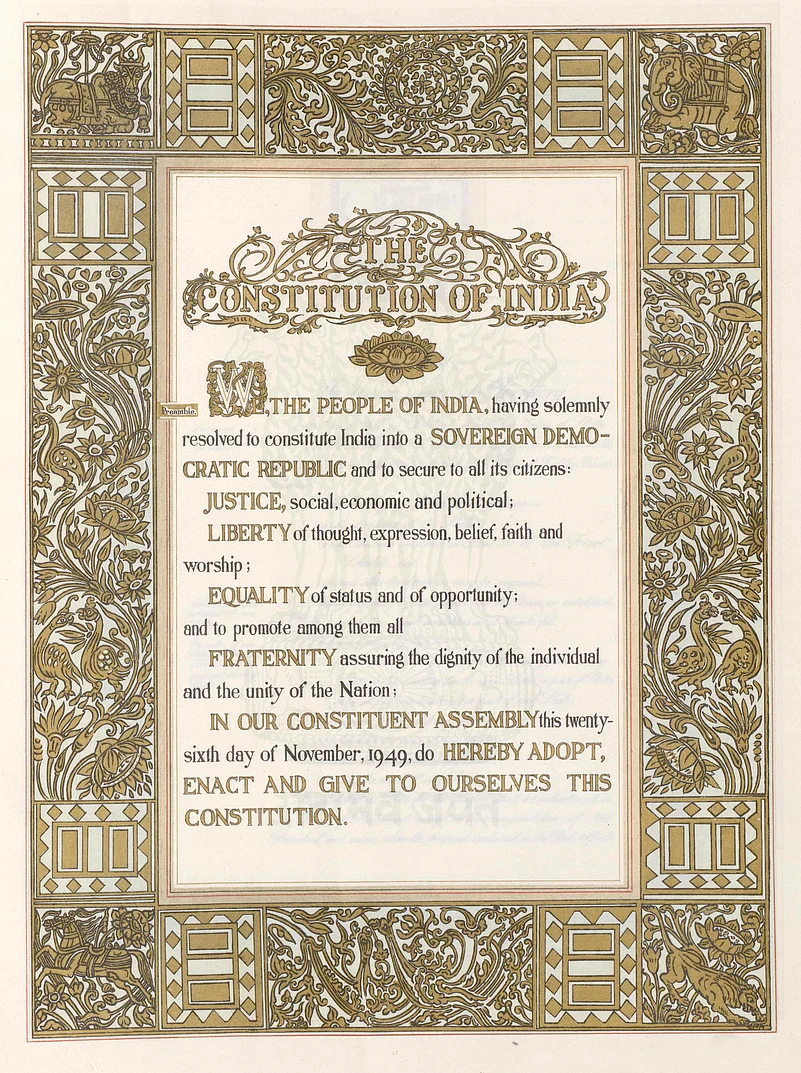

Much has been said about Republic Day and its significance, a truth we carried with us long before we learned to grasp its meaning. This year marks India’s 77th Republic Day, commemorating the day the Constitution of India came into force on January 26, 1950, formally establishing the nation as a ‘Sovereign Democratic Republic’.

BR Ambedkar led a key seven-member committee tasked with drafting one of the world’s lengthiest constitutional documents, comprising 395 provisions.

Between India’s independence and the coming into force of the Constitution, a 299-member Constituent Assembly laboured through the upheavals of Partition, communal violence, and the immense task of an ancient civilisation remaking itself into a young, emerging democracy.

The final version of the Constitution was signed by members of the Assembly on January 24, 1950 and came into force two days later with a 21-gun salute and the unfurling of the Indian National Flag by Dr Rajendra Prasad.

The Constitution now lays the foundation of democracy in the country. Yet, the journey from Independence to becoming a Republic was long, shaped by defining national moments and urgent calls for momentum, before it finally found expression in the opening words of the Preamble: “We, the People of India.”

The road to the Republic began with a decisive shift in political demands. In 1929, the Indian National Congress, meeting at its historic Lahore session, adopted the call for Purna Swaraj, or complete independence. This came after negotiations between Indian leaders and the British collapsed over the question of granting India dominion status.

The immediate backdrop was the Irwin Declaration of October 31, 1929, issued by Lord Irwin, then Viceroy of India. Framed as a conciliatory gesture, the declaration sought to reassure Indian nationalists that Britain intended, at some point, to help India attain dominion status within the British Empire. However, conveniently, it offered no clear timeline.

Earlier, the Nehru Report of 1928 had articulated the demand for dominion status, stating that India should enjoy the same constitutional position within the British Empire as Canada or Australia. While such demands had surfaced intermittently in the early decades of the 20th century, they gained wider acceptance only after the Government of India Act, 1919, which reshaped India’s constitutional framework without granting real self-rule.

The Irwin Declaration itself was a brief, five-line statement written in simple, non-legal language. Its vagueness, lack of concrete actions and backlash in England frustrated Indian leaders.

With only half-promises on the table, the nationalist leadership abandoned the demand for dominion status and instead raised the call for Purna Swaraj—complete and uncompromising independence. January 26, 1930, was declared the first Independence (Swarajya) Day and was to be observed across the country.

At midnight on New Year’s Eve, Jawaharlal Nehru, then President of the Indian National Congress, hoisted the tricolour on the banks of the Ravi in Lahore, marking a turn in India’s freedom struggle that eventually led to its independence and declaration of a Republic almost two decades later, however, not without its contradictions.

Ambedkar, Chairman of the Drafting Committee, himself stated how with India becoming a Republic, “we are going to enter into a life of contradictions. In politics we will have equality, and in social and economic life, we will have inequality.”

In his historic November 25, 1949, speech to the Constituent Assembly, Ambedkar said that the real credit for preparing the draft of the Constitution should first go to B.N. Rao and then to the main draftsman, S.N. Mukherji.

Ambedkar, an advocate of revolutionary state socialism in the Constitution, said: How long shall we continue to deny equality in our social and economic life? If we continue to deny it for long, we will do so only by putting our political democracy in peril.

Another major debate centred on federalism. The Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946 proposed a “federal union” in which the Centre would control only three subjects — defence, external affairs and communication — while the provinces retained all remaining powers. However, Partition in 1947 and its violent aftermath forced a rethinking of this model, leading to the idea of “a federation with a strong Centre”.

This shift was reflected in the Constituent Assembly debates. Veteran Bihar leader Brajeshwar Prasad warned against excessive provincial autonomy, stating, “I am opposed to federalism because I fear that with the setting up of semi-sovereign part-states, centrifugal tendencies will break up Indian unity.”

At the same time, concerns were raised about excessive centralisation. Congress leader T T Krishnamachari urged to outline a three criteria test for states: “states must exercise compulsive power in the enforcement of a given political order”; that “these powers must be regularly exercised over all the inhabitants of a given territory”; and, most importantly, “that the activity of the State must not be completely circumscribed by orders handed down for execution by the superior unit.”

Ambedkar clarified that the “basic principle of federalism” lay in the division of “legislative and executive authority” between the Centre and the states, a division made “not by any law to be made by the Centre but the constitution itself.”

Article 1 of the Constitution describes India as a “Union of States”, notably avoiding the word ‘federal’. Powers are clearly distributed through the Union, State and Concurrent Lists. Yet this arrangement has drawn criticism, particularly because the Centre can dominate the Concurrent List and, under certain conditions, legislate on State List subjects.

Ambedkar cautioned against over-centralisation, warning during the debates, “We must resist the tendency to make it (Centre) strong. It cannot chew more than it can digest. Its strength must be commensurable to its weight.”

These issues acquire even greater relevance in the present context, with the government at the Centre also ruling a majority of states, and with the use of provisions such as Article 359. In an era of superseding political mandates and governments that seem to conveniently amend the Constitution, it becomes important to ask who “we”, as a Republic, truly are — the “we” who give voice to the opening words of the Preamble of India.

At Outlook Magazine, we've asked the question: How far have we come and which are the challenges before the Repubic?

In our issue dated February 28, 2022, we examined the debates on federalism and sought to understand how this struggle has been shaped in recent times.

In 'Renegotiating India’s Federal Compact’, Yamini Aiyar wrote how this model of federalism, with a strong Union and intergovernmental dependence, served India well, despite routine misuse of its powers by the Union.

However, “the emergence of BJP as a single party majority in 2014 has fundamentally changed that federal bargain, both because it has put a pause to the increased presence of regional parties in national politics, but also because the BJP’s penchant for centralisation has opened new sites of contestation in India’s federal bargain. Thus, federalism today is both more vulnerable and unexpectedly more resilient.”

In Right In The Centre, Harish Khare notes the historicity of India's Constitution and its implementation in varying socio-political realities; alongside workability of the States and the Centre.

“As a primary covenant, the Constitution prescribed as well as proscribed working of a few basic relationships: The Union and the States, the Centre and the Periphery, the State and the Citizens, the Majority and the Minorities; and, the Executive-Judiciary; each relationship is defined by limits, to be observed by all constitutional players. The framers had aimed for a dynamic equilibrium as we would undertake the task of cobbling together a modern state and a vibrant political community.”

Another debate revolved around the inclusion of the word secularism. In Outlook Magazine’s November 21, 2022 issue, The Secularism Question, Abhik Bhattacharya writes about the beginning of the debate, with discussions on concepts of secularism to God to Power Politics as A Test Of Indian Secularism.

H.V. Kamath started the discussion by moving an amendment that proposed to start the Preamble with ‘In the name of God’. Following Kamath, Shibban Lal Saksena and Pandit Govind Malviya also moved similar amendments and said that it was under no circumstances ‘anti-secular’ and of ‘narrow, sectarian spirit’ as termed by Pandit H.N. Kunzru. Rather, citing the use of the word ‘God’ in the Preamble of the Irish Constitution, Malviya said that by invoking phrases like “By the grace of the Supreme Being, lord of the universe, called by different names by different peoples of the world”, they were not sanctifying God of any particular religion and hence must not be considered contrary to the spirit of secularism.

SY Quraishi speaks of the viability of the India’s secular tradition and its commitment to diversity in ‘A Walk Through The Several Decades Of Indian Secularism’.

“Constitutional secularism is of immense import to our notions of citizenship, nationality and civic freedom. Apart from the obvious effects that a crisis in secularism is registering in the electoral realm, we must also pay attention to how that crisis is creeping into other sectors of our nation’s life, ranging from our national media to education to the everyday life of a citizen.”

The questions of secularism, its inclusion in the Preamble through a constitutional amendment, and the rise of right-wing politics in India have deeply shaped the functioning of the Republic. These shifts have had tangible consequences, with minorities and marginalised communities often finding themselves struggling to access the Justice, Liberty, Equality and Fraternity promised by the Constitution.