Summary of this article

Republic Day is widely observed by teenagers as ritual, with the Constitution remaining distant and abstract.

Young people are shaped as much by the internet and visual media as by formal civics education.

Without conversation and lived context, constitutional values risk becoming performative.

For a long time, Republic Day was simply “a holiday when you had to go to school.” The flag-hoisting, the speeches, the national anthem— all seemed like duties to be performed rather than ideas to be inhabited. Between my time and my son’s, much has changed. There is the internet, for one. There is also a visible expansion of children’s and young adult literature on the Constitution, citizenship and rights, alongside a more performative, globalised idea of diversity. And yet, the narrative around Republic Day remains stubbornly familiar, and only superficially different.

School celebrations today often mirror this contradiction. A principal’s address on the success of the Indian diaspora abroad. A tribute to a long-serving physical education teacher whose legacy still inspires affection decades later. A cultural programme stitched together with Bollywood dance numbers that bear little relation to the gravity of the day. A student band—made up of teenagers from different countries—playing Jana Gana Mana and Sare Jahan Se Acchha. The spectacle is earnest, even moving, but the meaning remains diffused.

When teenagers speak about Republic Day, their responses range from indifference to discomfort to quiet reflection.

“It mostly means a school assembly where we stand in the sun and listen to speeches we don’t really understand,” one says.

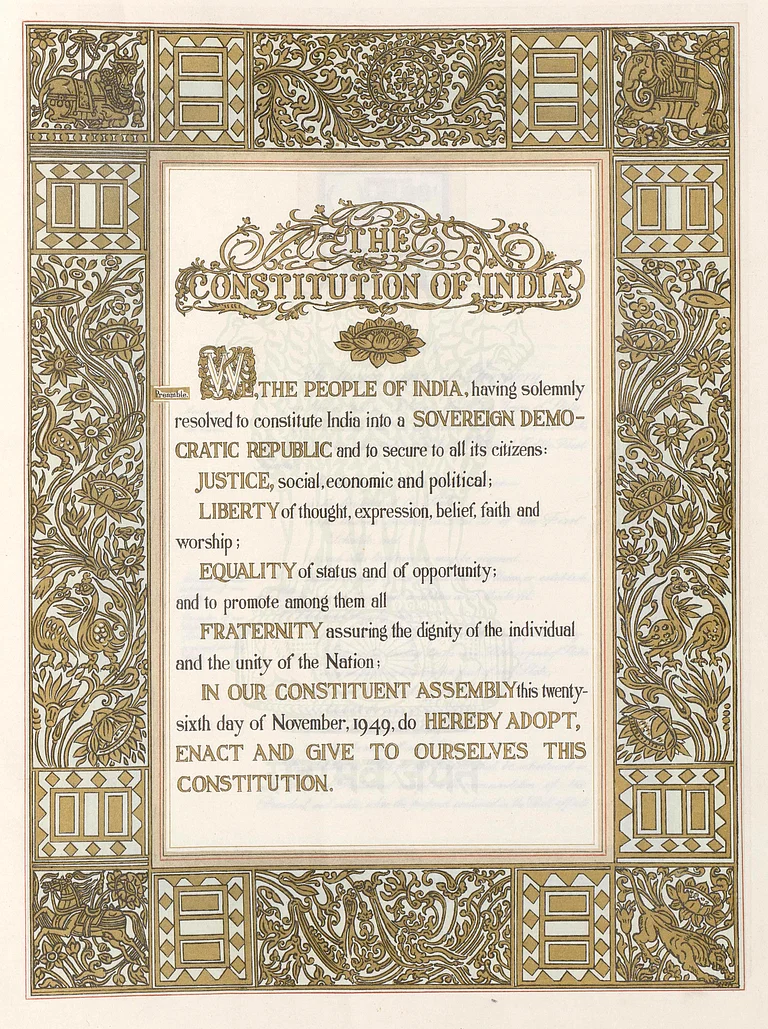

Another recalls being asked to memorise the Preamble in middle school—without any explanation of what it meant beyond the test.

“I know Republic Day is about the Constitution,” a teenager admits, “but the Constitution feels like something for courts and politicians, not for people our age.”

And then there is the unease around secularism. “We’re told India is secular,” one student says, “but online it feels like everyone is choosing sides. It’s confusing to know what you’re supposed to believe.”

Older young adults articulate this disquiet more sharply. “I think the drafters of the Indian Constitution took into account both immediate and future dangers when they wrote it,” says Trisha Ganesh, 21. “The Constitution itself is solid. The problem has always been selective implementation. And now it feels like it’s in danger of being disregarded altogether.”

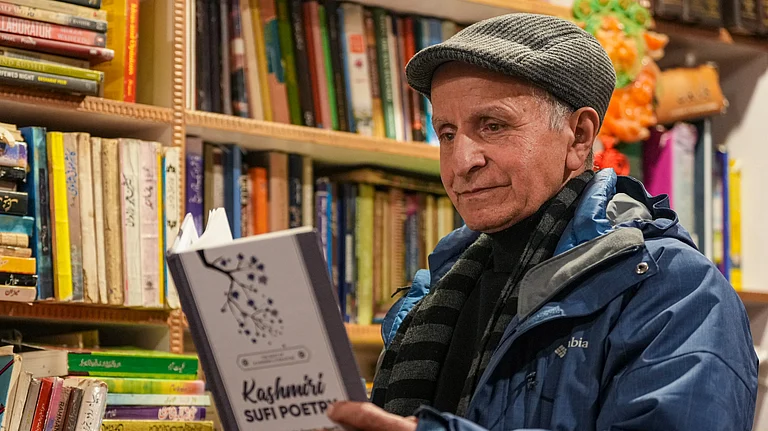

If the Constitution feels distant to many teenagers, it isn’t for lack of books attempting to explain it—but for how, and by whom, those explanations are offered. Mukunda Rao’s work occupies a distinctive place in this landscape, shaped as much by his life as by his writing. Trained as an engineer and long employed in the corporate world, Rao came to the Constitution not as a lawyer or academic, but as a citizen unsettled by how little everyday India—especially children—understood the document that governs their lives. His decision to step away from professional certainty and dedicate himself to constitutional education was driven not by authority, but by unease: the sense that something foundational was being inherited without context, conversation or care. That outsider’s curiosity animates The Constitution of India for Beginners, which treats liberty, equality and secularism not as legal abstractions or patriotic slogans, but as ethical questions rooted in daily life—at home, in classrooms and in public spaces.

The same impulse shapes Babasaheb Ambedkar: An Inspirational Life, which resists turning Ambedkar into either a distant icon or a simplified hero. Instead, Rao presents Ambedkar as a thinking human being—formed by humiliation and exclusion, sharpened by education, and committed to constitutional morality as a way of organising a deeply unequal society. Read alongside his Constitution primer, the biography becomes less a standalone life story and more an argument: that the Republic, as Ambedkar imagined it, requires active, questioning citizens rather than obedient subjects.

Other children’s books gesture in similar directions. Leila Seth’s We the Children of India assumes curiosity rather than compliance, inviting young readers to see themselves as stakeholders rather than spectators. Subhadra Sen Gupta’s Our Constitution, often encountered in school libraries, offers clarity and structure but remains closer to the language of examinations than lived experience - useful, yet rarely returned to once the test is over. Increasingly, it is graphic narratives—from Amar Chitra Katha editions on Ambedkar to visual explainers circulating through platforms like PARI - that have become the entry point through which teenagers encounter ideas of rights, protest and citizenship.

A younger voice puts it more simply. “A Constitution isn’t just a book of rules,” says eleven-year-old Meera Basrao. “It’s a document to serve the rights of a citizen— of what India is , what a citizen means, what a citizen does - to be a great human being in their country.”

And yet, most teenagers, although they recognise the constitution as something important, still struggle to see it as something that belongs to them. But one thing emerges quite clearly. The Constitution as a once-a-year performance is not enough. As Mukunda Rao’s work suggests, it was meant to be lived, questioned and argued with. If teenagers struggle to see themselves in it today, it may be less a failure of attention than of invitation. Republic Day, then, becomes not a celebration of what they know—but a reminder of what we haven’t yet taught them to claim.