Summary of this article

Household culture and food are the most unifying strands in the ethno-linguistically diverse Hindi heartland region.

After culture, food is the most important unifying factor

People adopted Hindi only because it was linked with employment, says Wahab, in conversation with Outlook Editor Chinki Sinha

From the Rajasthan deserts in the west to the fertile middle-Gangetic plains in Bihar in the east and from the Himalayas in the north to central India’s Vindhya hills in the south—different regions in this huge tract of land have been clubbed under several umbrella identities: from Aryavarta in the post-Vedic period to Hindi belt or Hindi heartland in recent decades.

This region faced most of the foreign invasions and migrations from the west. This is where the Aryans first built their Vedic civilisation before spreading eastwards to the Bengal delta and southwards beyond the Vindhya. This is where the first Muslim dynasties came up. India’s largest empires—from Maurya to Mughal—were headquartered here.

The region has remained different from other parts of India in several aspects. This is India’s vegetarian heartland. It’s considered more overtly religious than other parts of the country. It’s from here that Hindutva politics first took its roots in postcolonial India. Right now, this heartland is in the middle of aggressive cultural politics against its syncretic, diverse past.

Among many similarities and diversities, ‘Hindi’ appears to have emerged as the unifying factor in present times, as frequent references to this region as the ‘Hindi belt’ or ‘Hindi heartland’ reflect. However, journalist Ghazala Wahab, author of the 2025 book, ‘The Hindi Heartland: A Study’, disagrees. She finds household culture and food as the most unifying strands amidst this ethno-linguistically diverse region.

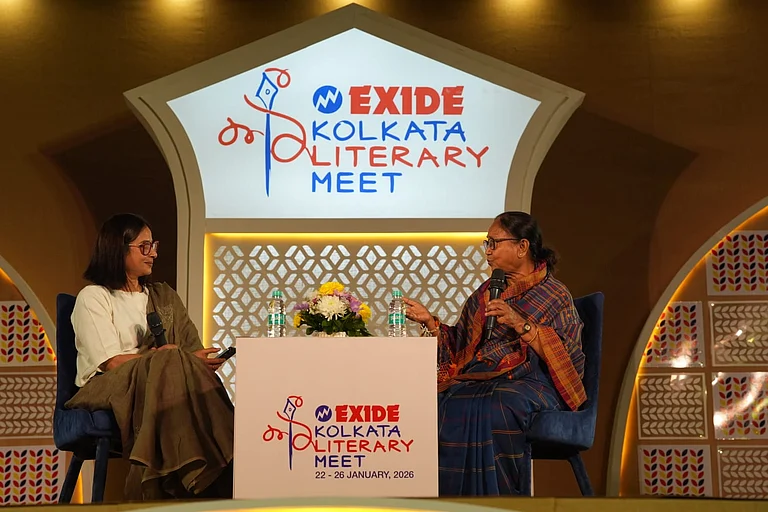

“Hindi is nobody’s language. None speaks Hindi. People speak their own mother tongue, whether it's Awadhi, Magahi, Maithili, Bhojpuri or Rajasthani,” Wahab says while discussing her book with Outlook Editor Chinki Sinha on the third day of the Exide Kolkata Literary Meet, a five-day festival.

Wahab argues that these languages predate Hindi, which was created by sourcing materials from these languages. This is why people do not have the natural affinity with Hindi that they share with their mother tongue. People adopted Hindi only because it was linked with employment. Therefore, Hindi does not serve as the common thread binding the region. Rather, the region’s culture and food do.

By culture, she did not mean the ‘high’ or ‘fine’ culture concerning art, literature or music—fields dominated by men. It’s the culture at the grassroots level that she finds most common across the region.

As she puts the detailing of women-centric customs and cultures in the book in the context of the conflict between people’s inherited memory and official history of the present time, Wahab says it is in household culture, including customs and rituals, that the correct memory of collective living in the Hindi heartland can be found. Wahab argues that household culture, whether family traditions or ceremonies pertaining to birth, celebration of womanhood, marriage and death, remained women’s domain, one that men rarely interfered with. This space remained religion agnostic.

“In the entire Hindi belt, in both Hindu and Muslim families, similar kinds of colours are considered sacred, celebratory or mournful. Pre-wedding ceremonies and post-death rituals have similarities, too,” she says. Besides, it’s mostly the women—both Hindu and Muslim—who visit the Sufi shrines, symbols of syncretic culture that dot the region. They share similar kinds of anxieties and prayers.

Wahab calls this household culture, communicated from one woman to another over generations, “a repository of our composite living together” that gives India its biggest strength.

This is more so at a time “history is being revised and our memories are being changed so that we regard our past as completely divisive and always hostile to one another,” she says.

After culture, food is the most important unifying factor. She gives the example of litti-chokha in Bihar and dal-bati in Rajasthan, with litti and bati being identical; and the birista (finely chopped, deep-fried onion) popular across the region, cutting across religions.

Wahab insists that a deeper look at the history of the region through household customs and rituals reveals the happenings in the past were not as ugly as what we would now like to believe.

“Our greatest strength came from diversity, which was beneficial to everyone. Everyone thrived from diversity. We need to reclaim that,” she says, adding, “We need to understand where we have come from if we have to resist the kind of divisiveness that is happening and the politics being played.”