India’s school history textbooks underwent an overhaul in 2025.

Class VIII Social Science books now skip the post-Aurangzeb era, moving straight from the Gupta Empire to British colonial rule.

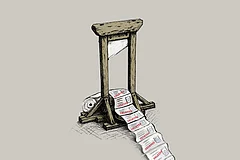

These changes have sparked a national debate over history education: how much to streamline vs. how much to cover, and whether the new narrative serves educational goals or political ends.

In August 2025, the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) released two new modules titled ‘Partition Horrors Remembrance Day’ for Classes VI to XII. As of 2024 and early 2025, there are more than 27 million students enrolled in Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) schools, with approximately 20 million kids in India.

News of these additions to the CBSE school syllabus has made headlines.

In a section titled “Culprits of Partition,” the NCERT module says, “Ultimately, on August 15, 1947, India was divided. But this was not the doing of any one person. There were three elements responsible for the Partition of India: first, Jinnah, who demanded it; second, the Congress, which accepted it; and third, Mountbatten, who implemented it. But Mountbatten proved to be guilty of a major blunder.”

NCERT published two separate modules: one module for Classes VI to VIII and another for Classes IX to XII. These resources are intended to be supplementary in English and Hindi and are not yet part of regular textbooks. These modules are designed for use in projects, posters, discussions and debates.Both modules open with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 2021 message announcing the observance of Partition Horrors Remembrance Day on August 14.

The modules include notes that Mountbatten made a fatal mistake in that he hurried the transfer of power, moving the date of India’s Partition from 1948 to August 1947, which gave Sir Cyril Radcliffe mere weeks to draw borders between India and Pakistan. Even Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel is quoted as saying, the Partition was “bitter medicine” to avoid civil war, along with Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s quote that he “never expected to see Pakistan” in his lifetime.

The module framework has led to a political clash between the ruling BJP and the Indian National Congress. The latter’s spokespersons have denounced the changes, calling them misleading. Congress leader Pawan Khera demanded that the NCERT withdraw the module. He said the new additions ignore the Hindu Mahasabha’s pre-1938 role in advocating for this division.

Historian Janaki Nair notes that the new modules aim to teach children to take pride in specific aspects of their heritage. Calling this a “tendentious approach to Partition”, she points out that the new modules do not “acknowledge at least four decades of research on Partition, which is much more nuanced, and acknowledges that the violence is difficult to characterise since it was so widespread, and victims could become perpetrators and perpetrators could become victims. Even the armies were not above attacking the very people they were supposed to protect.”

She adds that “through a partial citation of sources (both the included newspaper cuttings depict violence against Hindus, presented as an attempt to give a veneer of objectivity to the historical method used) it suggests strongly that the violence was one-sided, while also ignoring the excellent work done by feminist historians on the experience of women during the Partition, especially following the Abducted Person (Recovery and Restoration) Act of 1949.”

She alleges, “The most important goal of this chapter is to malign the Congress and to suggest that the Muslims who remained in India are an illegitimate population.”

Instilling National Pride, Or Rewriting History?

The Partition row is part of a broader argument about India’s freedom struggle curriculum. School staff note that since 2020 there have been significant changes in the history curriculum, with key historical flashpoints either deleted or significantly truncated. “The entire Mughal period has been erased. There is deletion of those people associated with the Mughals, and Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination has also been removed,” points out Jayashree Nair, principal of Brighton International School, a CBSE-affiliated school in Raipur.

Teachers and educationists say the changes are not limited to recent additions on Partition but reflect a wider reshaping of the history syllabus. This year, India’s school history textbooks have undergone an overhaul. Under the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 and the updated curriculum framework, the NCERT has shortened middle-school history. The Class VIII Social Science book now skips the post-Aurangzeb era, moving straight from the Gupta Empire to British colonial rule.

Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination and Nathuram Godse’s links to the Hindu right were deleted earlier this year, as was any mention of the post-1948 ban on the RSS. Similarly, incidents of communal violence in India, such as the 2002 Gujarat riots and the 1992 Babri Masjid demolition, have been deleted or cut down.

The NCERT says these cuts are to remove rote materials and “reduce overload.” These changes have sparked a national debate over history education: how much is to streamline and how much to cover, and whether the new narrative truly serves educational goals or politicises children’s education.

While some criticise the changes as skimming over India’s complex history, educationalist and former NCERT Director Krishna Kumar says the changes should not surprise anyone and are a sign of the times. “It’s driven by ideology,” he says. He adds, “These changes had started to come in during the COVID period. CBSE tweaked the syllabus. It took out many portions from the syllabus, and gradually, the tinkering and changes started. And now we have it in full form because there is a new curriculum framework. These are entirely new modules, and we’re going to see more and more of these kinds of textbooks.” Kumar says, “You can’t even call them changes in the old textbooks. No, these are new books.”

In 2023, when new textbooks were issued by the NCERT, the institute promised that the books were in line with the NEP goals. These included a balanced approach focusing on core narratives while reducing details that students would have to mechanically memorise.

However, as Kumar says, “Education is not some sort of a plant that you can put in a special room where you create a special atmosphere for education to grow. It’s part of the larger ethos, part of the larger political process. This vision of education matches this larger political reality of our country now. And we have to see it as that.”

What Are the Teachers Doing?

Principal Jayashree Nair says that the new curriculum has led to questions from her students. “Students have a lot of questions. They are really curious about it because this is the first time they are reading all these things. They are not on social media and cannot access all these things. And yes, what is truth is truth. We cannot change it,” she explains.

Nair says that teachers now have the added task of balancing what is written in the books with other sources of historical record to provide a fair and accurate picture to their students.

The teachers have to explain the lessons “in keeping the beauty of the country, as we have so many religions and customs, culture, caste (and) creed living together,” says Nair, adding that “The teacher has to explain it in a proper manner. We all are living together. And we have to teach the children that we should have patience. We should have acceptance of others too.”

She recalls how teachers have pointed out to students that Indian Muslims, such as former President of India the late Abdul Kalam, have held esteemed positions in the country. “We say, would you want Abdul Kalam to go out of this country? No, the students reply, and we reply: exactly!”

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Avantika Mehta is a Senior Associate Editor based in New Delhi

Democracy is about ballots, but also about memory—who safeguards both, and who seeks to rewrite them? Outlook’s September 11, 2025 issue, 'Election Omission' probes these erasures—of voters, voices, and histories—asking what they mean for India’s democratic future. This article appeared in print as 'A Class Of Controversies.'

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=376&dpr=2.0)