Cruising past lush carpets of paddy and tall palm trees, our vehicle halted near a roadside fruit seller. He had spread on the ground two different types of mangoes, bananas and other fruits. The thick canopy provided him shelter from the heat. To our left, I could steal a glimpse of the alluring Cauvery River, the lifeline of the region. Two Hallikar bulls, native to Karnataka, were resting a few metres away from us. They perhaps belonged to the fruit seller. It is said that Tipu Sultan, the famed ruler of Mysore, had cross-bred the Hallikar bulls, identifiable by their long, vertical, backwards-bending horns, to give rise to the Amrut Mahal breed. A sturdier and more active cattle breed, Amrut Mahal was also successfully deployed during battles by Tipu till his death in 1799 in the fourth Anglo-Mysore war.

I was on my way to Srirangapatna, a town in Mandya district, around a 2.5-hour drive from Bengaluru, to gauge the local mood around Tipu Sultan. The ruler of Mysore has become a regular talking point in the elections in this state. Election trips tell us more than just voting patterns and issues concerning the public. They also provide us valuable snippets into the history as well the socio-economic situation of a place. More than gazing at the momentary mood of the public vis-à-vis the political parties, in my two days of travelling in Mandya and Mysore, I feel I was fortunate to learn many new aspects of the history of Karnataka, a state about which little is known or discussed by us who live in North India. These snippets of life and culture eventually help a journalist understand political trends better and beyond simple voting calculations. Let’s leave that to the survey agencies.

Our vehicle had just crossed the Atravatige Koppalu village election check post. Armed with a video camera to record the proceedings, police and district officials were checking vehicle after vehicle for illegal items used to entice voters and threaten opponents. "Looking for liquor?" I jokingly asked one of the officials in duty as his men were scouting the back of one of the SUVs. "Not just liquor, everything!” he quipped.

After driving from the state capital Bengaluru on the newly-opened Bengaluru-Mysuru Expressway, we reached the fort of Srirangapatna. While there was a lot of noise on television channels about the BJP’s newly-created theory that Tipu was killed by two Vokkaligas—Nanje Gowda and Uri Gowda—and not by the British, on the ground there was hardly a murmur about the issue. At the spot where Tipu was killed on May 4, 1799, a modest stone tablet erected by the government stood as a reminder of that day. The spot is an ASI-protected monument and even the Modi government’s own signboard there clearly states that Tipu was killed by the British.

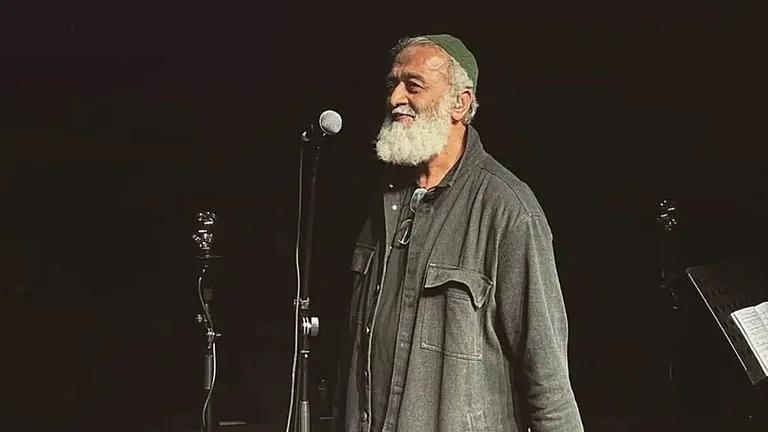

For all the political noise over his death, Srirangapatna was relatively quiet and Tipu was hardly a talking point, as it should be in 2023. From there, I headed to the Jama Masjid or the Masjid-e-Ala, a short distance away. The mosque, easily identifiable by its two imposing minarets, was built during the time of Tipu in 1784. Syed Raus had been waiting for me at the gate of the mosque. For almost two decades, he has been teaching English, computer and other subjects to the young students who come to the madrasa inside the mosque. Raus showed me around the complex where a group of boys and girls were receiving religious education as part of their summer camp. For an outsider, Tipu Sultan is a historical figure, to be studied, debated, loved or hated. For locals like Raus, Tipu was "Sultan", whose legacy still impacted their day-to-day existence. From agriculture to land reforms to children’s toys.

To know about this further, I decided to travel further ahead to Kirugavalu village. Otherwise a nondescript place today, it once held a small watch tower that Tipu's forces used to monitor the movement of the British. I was there to meet Syed Ghani Khan, a young farmer who had gained repute for growing over 100 varieties of mangoes dating back to the times of Tipu. The story goes that Tipu donated the land in and around the village to soldiers after he disbanded the army. He encouraged them to grow different varieties of mangoes. Ghani, also known for cultivating and preserving around 1350 varieties of rice, shared his vision with me. It was humbling to learn about so many varieties of mangoes and rice. He told me about a mango that smelled of cumin, while another looked like a banana. A variety of mango was so liked by crows that it was named Kauwa Pasand (favourite of the crows). How little do we know about our fruits and the diversity of our country?

Khan seemed motivated by his efforts. He was also very humble despite knowing a lot about agriculture. But was also a tad disappointed that he never got his due recognition from the government.

An election trail not only tells us about what citizens think of politicians or which way they will vote and why but also brings us closer to ordinary people we would have otherwise never encountered. After a fruitful meeting with Khan at his farm, we headed to nearby villages to speak to Vokkaliga farmers to understand what they thought of Tipu and BJP's renewed outreach among the community for votes. As none of them understood Hindi or spoke English, I had to take help from our car driver Narasimha Gowda, himself a Vokkaliga. Though he managed to translate basic ideas, a lot of humour, expressions and metaphors were lost in translation, if I may deploy a cliche.

We passed through Mysore city where after meeting the famous author PV Nanjaraj Urs at his residence, Narsimha Gowda helped me navigate the culinary road of the city famed for its culture. At Hotel Hanumanthu, a popular local joint, we enjoyed mutton leg piece soup and mutton pulav, local favourites. Having mostly covered elections before in the Hindi heartland and Maharashtra, I was struck by how different the eating habits in rural areas of Karnataka were. In the North, where vegetarianism, conservatism and majoritarianism often go hand-in-hand, I was pleasantly surprised to find that my driver, despite himself, not being a beef eater, was comfortable about having a chat on the subject with me. Gowda also guided me to the best place to purchase freshly ground coffee made in town.

A day prior to this, I visited the residence of Sunanda Jayaram, a prominent farmer leader in Mandya. A Vokkaliga, she described the interests of the farmers, especially around the Nandini vs Amul milk dispute. I was impressed by the conviction of her ideas. She recalled how when Kentucky Fried Chicken opened its outlet in Bengaluru, she had staged a protest against it as she is against the takeover of the business by big and multinational corporates.

While showing me around their farm, Jayaram and her husband pointed me to a woman farm labourer who was collecting fodder for her cattle. "She's the real farmer. Woman is the real farmer. The men just sit and count money. We do the actual labour," Jayaram said, laughing aloud. Although I, regrettably, do not speak or understand Kannada, I could gauge her sentiments through the passion with which she delivered those lines.

We nodded in agreement. Before leaving, she gifted me a bag of organic ragi grown in her field. Elections come and go. Power exchanges hand. But these conversations and little experiences stay with us forever.