The Tamil Nadu government and DMK deplore the allegation that Bihar migrant workers are ill-treated in the state.

The political stance against Hindi imposition in Tamil Nadu is often deliberately misconstrued as anti-North.

Tamil Nadu hosts about 2.5 million migrant labourers from Bihar.

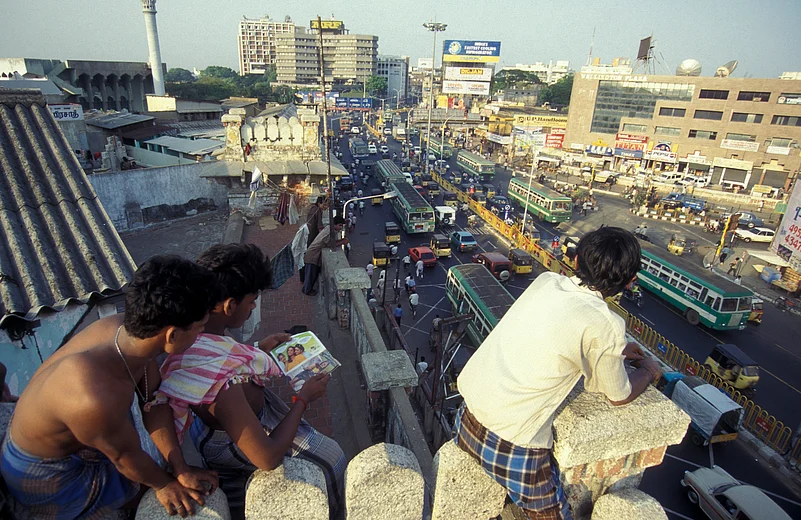

Tamil Nadu and Bihar are separated by more than 2,000 kilometres, and at first glance, there seems little to compare between the two. Yet, both states share a significant ideological lineage — each has been a laboratory for the politics of social justice. In Tamil Nadu, the self-respect movement evolved into the Dravidian political tradition, while in Bihar, the rise of backward caste politics placed affirmative action and social empowerment at the centre of India’s political discourse.

During the just-concluded Bihar Assembly election campaign, both the Prime Minister and the Home Minister invoked Tamil Nadu and its Chief Minister — not to highlight any ideological common ground between the two distant states, but to make allegedly disparaging remarks. The Prime Minister alleged that migrant workers from Bihar were being harassed in Tamil Nadu by DMK cadres. The insinuation that Tamilians are hostile to Hindi-speaking Biharis did not go down well with the DMK or Chief Minister M.K. Stalin.

Despite sharp reactions from Tamil Nadu’s political leaders, the BJP continued its offensive. Taking a jibe at RJD leader Tejashwi Yadav, Union Home Minister Amit Shah said that Tejashwi’s “favourite Chief Minister,” M.K. Stalin, had insulted Biharis by comparing them to beedis. “Someone asked Lalu’s son who his favourite CM is. He said DMK’s Stalin, who is the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu. Do you know who he is? I’ll give his introduction—his party compares Biharis to beedis and insults them,” Shah remarked at an election rally.

Tamil Nadu is home to 35 lakh migrant workers.

Both statements — one by the Prime Minister and the other by the Home Minister — drew sharp reactions from the DMK and its allies. Chief Minister M.K. Stalin dared the Prime Minister to repeat such “disparaging” remarks during a visit to Tamil Nadu. He said Biharis are hardworking people and that there has been no incident of targeted attacks against migrant workers in the state.

“This is a state of fraternity and brotherhood that welcomes and nurtures those who come here. Yet, Modi forgot he is the Prime Minister for all and chose to spread falsehoods in Bihar. I dare him to come here and make the same speech,” Stalin told reporters on the sidelines of a function.

According to the Tamil Nadu State Planning Commission, there are around 35 lakh inter-state migrant workers in the state. Of these, more than 2.5 lakh are from Bihar, making them the second-largest migrant group after workers from Odisha.

The Report on Life and Times of Migrant Workers in the Chennai Region – 2024-25, released by the State Planning Commission, noted that a majority of migrant workers in the Chennai region — comprising Chengalpattu, Chennai, Kancheepuram, and Tiruvallur districts — are from the eastern and northeastern parts of the country, particularly Bihar, Odisha, and Assam.

Even before the Prime Minister and the Home Minister levelled allegations of ill-treatment of migrant workers in Tamil Nadu, there had been concerted attempts by certain groups to spread fake stories of attacks against them. In 2023, a spate of social media posts circulated videos of unrelated incidents from other parts of the country, falsely claiming them to be assaults on migrant workers from Bihar. Swift action by both the Tamil Nadu and Bihar governments, along with police investigations and the registration of cases, helped put an end to those rumours.

“It is unfortunate that the Prime Minister and the Home Minister are spreading false narratives about a state that cares for and provides opportunities to migrant workers,” says DMK MP Dr P. Ganapathy Rajkumar. “My constituency, Coimbatore, has thousands of migrant workers, and I have never come across a single case of ill-treatment,” he tells Outlook.

He adds: “The same holds true across the state. We treat everyone equally, without any bias based on language, religion, or race. Our opposition is only to the imposition of Hindi, not to those who speak the language.”

DMK Vs BJP

Since the DMK came to power in 2021, Tamil Nadu has been vocal in resisting several Union government policies that it believes encroach upon the state’s rights. The DMK government has repeatedly taken the Centre to task — from accusing it of withholding funds to clashing with the Governor over delayed assent to bills passed by the Assembly.

The state has also approached the Supreme Court, alleging that the Centre has stalled the release of Rs 2,000 crore in educational funds under the Samagra Shiksha scheme. It continues to oppose the National Education Policy (NEP) and the three-language formula. In a major legal victory for Tamil Nadu, the Supreme Court recently set a time limit for Governors to act on bills passed by state legislatures — a move seen as a setback not only for the Governors but also for the Union government, which has been accused of using Governors to interfere in state affairs. The Centre, in response, has filed a Presidential Reference, on which the Supreme Court is yet to deliver its verdict.

All this has deepened the ideological acrimony between the DMK government in Tamil Nadu and the central government led by the BJP.

The BJP’s antagonism toward southern states is not new. During the 2016 Assembly election campaign, Prime Minister Narendra Modi compared Kerala to Somalia — a remark that provoked widespread outrage across the political spectrum. The comparison, made against a state that consistently tops India’s Human Development Indices, was seen as both inaccurate and condescending.

Part of a larger pattern?

Is there an ideological reason behind the BJP’s repeated targeting of southern states? Dr Ajay Gudavarthy, political theorist and Associate Professor at the Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, offers a measured explanation. He sees it as part of a broader political pattern.

“The attacks on Kerala and Tamil Nadu are a continuation of the conflicts the current regime has stoked elsewhere — portraying Sikh farmers in Punjab as Khalistanis, Buddhist tribals in Ladakh and Christian tribals in Manipur as threats, and, of course, vilifying Indian and Kashmiri Muslims,” Dr Gudavarthy tells Outlook. “It reflects a larger strategy of the present dispensation to foster a siege mentality and consolidate the Hindu vote bank in the Hindi heartland.”

While political expediency may explain recurring criticisms of southern states, underlying structural challenges have the potential to turn the perceived North–South divide into a more significant issue.

For years, southern states have raised concerns about the criteria used to allocate central funds. They argue that their success in population control and education has ironically worked against them, resulting in smaller shares from the divisible central pool. Adding to this unease is the proposed delimitation exercise scheduled for the coming years. Having achieved demographic stability, these states fear that their number of Lok Sabha seats could shrink, leading to diminished political representation in Parliament.

Those challenges may play out later, and one hopes that the leadership on both sides will find an amicable resolution. For now, migrant workers — in whose name political battles are being waged — remain largely untouched by these allegations. They continue to live and work peacefully in distant lands, contributing silently to the economies of the very states caught in this political crossfire.