Summary of this article

Teenage grief is often misunderstood and overlooked, even as books and films reflect how deeply loss shapes adolescent lives.

India’s mental health and school systems lack clear frameworks to recognise or support grieving teenagers, focusing instead on anxiety and depression.

The cost of this neglect is long-term, with unresolved grief resurfacing as emotional distress, disengagement, or risk-taking later on.

In Dustin Thao’s novel You’ve Reached Sam, grief begins with an impossible phone call. A teenage girl, unable to accept her boyfriend’s sudden death, dials his number—and hears his voice on the other end. The moment is fantastical, but the grief that follows is not. It is repetitive, disorienting, and unresolved—exactly the way many adolescents experience loss.

That realism may explain why novels like Thao’s give language to an experience that remains largely invisible outside fiction: teenage grief as a defining event rather than a temporary disruption. It cannot be hurried toward healing; it needs to linger, to interrupt school days and friendships, to reshape identity. It is a truth adolescents recognise instinctively but are rarely allowed to voice: that grief at this age is not smaller, simpler, or more resilient than adult grief. It is often lonelier.

Outside fiction, teenage grief rarely announces itself in ways adults recognise. It does not always look like tears or withdrawal. More often, it appears as irritability, disengagement, risk-taking, academic decline, or emotional numbness—responses that are quickly disciplined, diagnosed, or dismissed. What is missing, almost entirely, is a policy vocabulary for adolescent grief.

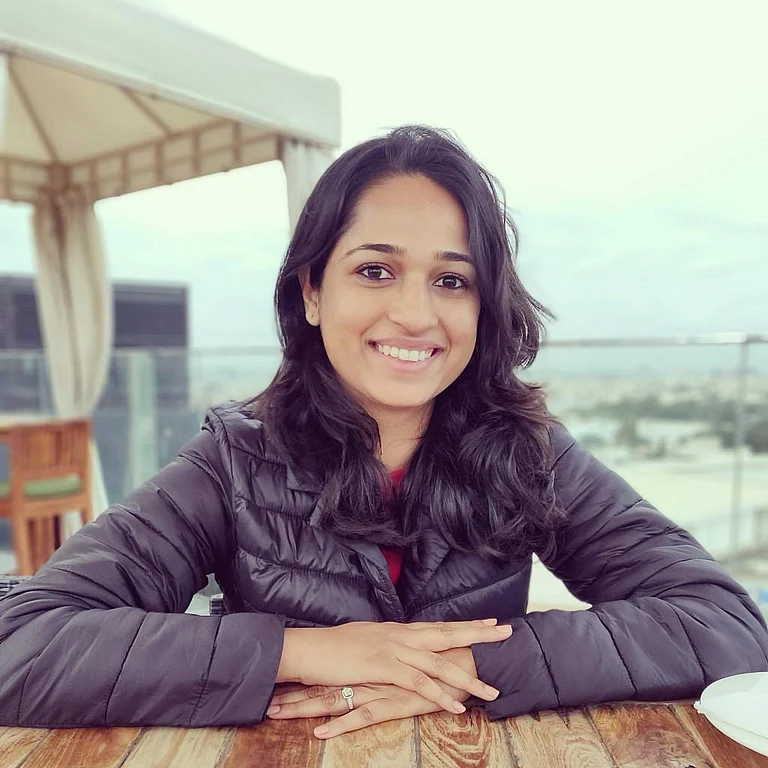

Vasundhara Sanghi, a psychologist and therapist who works with adolescents recalls counselling a young teen who had lost an older sibling. People who were coming for condolences would say, “be strong for your parents”. Finally, the teen said, quietly, “What about me? My parents had a whole life before my sibling. I only knew life with my older sibling. I feel so alone because no one understands this.” The statement was not defiance. It was erasure.

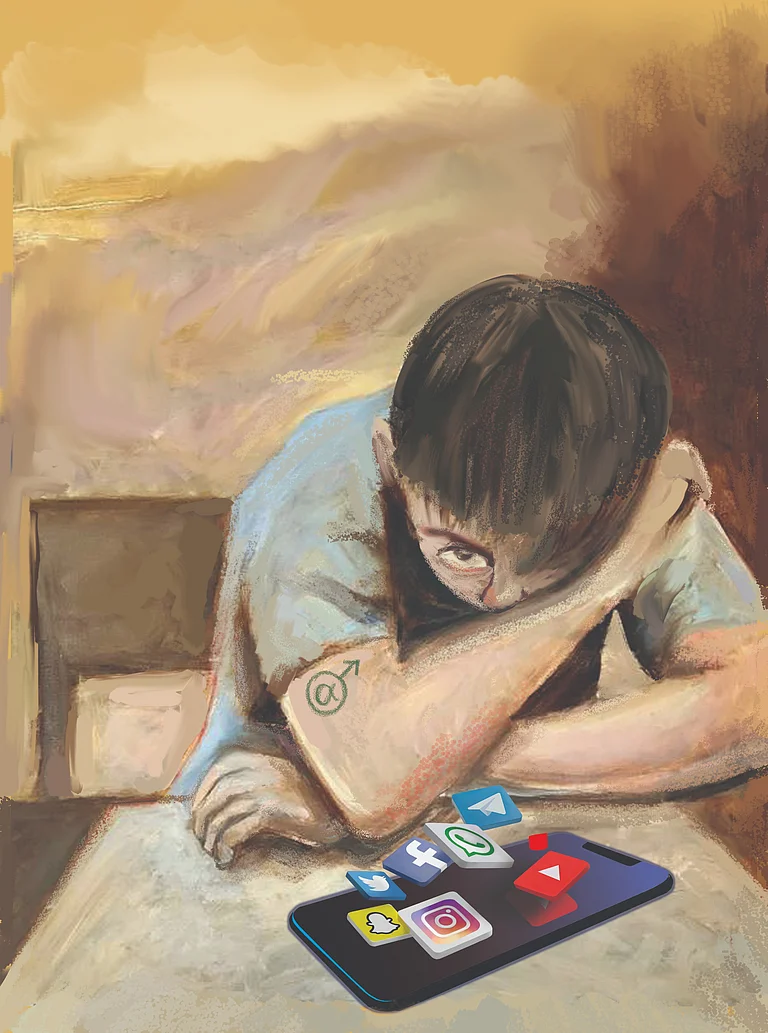

In families, schools, and even clinical settings, teenage grief is often subordinated to adult loss. Parents are understandably seen as the primary mourners; younger siblings are expected to adapt. But research on adolescent and peer loss suggests that for teenagers - whose sense of self, safety, and belonging is still forming - bereavement can be profoundly destabilising. Sibling and peer deaths are linked to higher risks of depression, anxiety, academic disengagement, identity confusion, and emotional distress that may resurface years later. Yet this evidence rarely translates into structured, sustained support.

One reason is that grief does not fit neatly into existing mental health categories. Anxiety and depression have diagnostic frameworks, screening tools, and treatment pathways. Grief, especially in adolescents, sits uncomfortably between normal life experience and clinical concern. It is neither always classified as trauma, nor easily absorbed into mood disorders. As a result, it is often medicalised too quickly or overlooked altogether.

Dr Pervin Dadachanji, a child and adolescent psychiatrist, describes adolescent grief as a distinct psychological experience that is frequently misunderstood. “Unfortunately, adolescent grief is either clubbed with adult grief or not taken seriously,” she says. The risks of this dismissal are significant: unresolved grief can later surface as depression, suicidal ideation, risk-taking behaviour, guilt, and difficulties with identity formation—particularly when a parent’s grief eclipses the adolescent’s own.

Adolescents, she adds, are also adept at masking distress. Vulnerability is uncool; help is often resisted even when offered. Combined with the widespread belief that children are naturally resilient and will “bounce back”, this means teenage grief frequently falls through the cracks of mental health systems.

Schools, where adolescents spend most of their waking hours, are often the first institutions to observe behavioural changes after a loss. Yet responses to bereavement remain largely ad hoc. There are few mandated protocols for how schools should respond when a student loses a sibling, parent, or peer. Academic expectations are rarely adjusted beyond a brief window. Teacher training seldom includes guidance on grief, and routine mental health screenings do not explicitly assess for loss.

Dadachanji argues that schools must be recognised as critical sites of intervention. Addressing grief openly—“naming the elephant in the room”, as she puts it—can make a meaningful difference. Sensitising classmates, assigning a peer buddy, regular check-ins with a counsellor, and temporarily de-emphasising academics in favour of emotional stability are not extraordinary measures. They are basic acts of care, she reminds.

In India, however, this neglect is also structural. While adolescent mental health has gained visibility through initiatives such as the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) and the Tele MANAS helpline, grief is rarely addressed as a distinct concern within these frameworks. School mental health guidelines focus largely on stress, anxiety, behavioural issues, and exam pressure, with bereavement treated as a short-term disruption rather than a condition requiring follow-up care. The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017, though progressive in affirming access to mental health services, does not explicitly account for age-specific grief support or mandate post-bereavement interventions for minors. As a result, responses to adolescent loss remain inconsistent—dependent on individual schools, counsellors, or families rather than embedded policy. What exists is access to care in theory, but little guidance on how grief should be recognised, tracked, or supported over time for teenagers.

Some of the most effective support, Dadachanji notes, is also the simplest: one consistently compassionate adult, validation of the adolescent’s feelings, stable routines around sleep and nutrition, and access to peer support groups. In her work facilitating grief group counselling for young people bereaved by suicide, she has seen how transformative it can be for teenagers to realise that their grief is neither abnormal nor invisible.

That this recognition appears more readily in fiction than in policy should give us pause. Novels by writers like Dustin Thao, along with a growing number of films and series centred on adolescent loss, allow teenage grief to be messy, unresolved, and central. They reflect a public intuition that young people’s losses matter deeply—even when institutions fail to keep pace.

Culture, after all, is often the first place where silences break. Policy tends to follow later, if at all.

The question, then, is not whether teenagers grieve. It is whether India’s mental health and education systems are willing to recognise adolescent grief as a legitimate, lasting experience and to respond with structures that do not ask young people to disappear into resilience.