Summary of this article

Once marginalised by behavioural psychology and pharmaceutical approaches, psychoanalysis is regaining prominence in media, academia and online culture, with renewed interest in Freud’s ideas.

Today’s resurgence is fuelled by global instability, dissatisfaction with quick-fix mental health treatments, and a renewed search for deeper explanations of human behaviour and collective anxiety.

Once dismissed as outdated and unscientific, psychoanalysis is staging an unlikely comeback — drawing millions of followers online, re-entering mainstream cultural debate and reasserting itself as a tool for understanding trauma, authoritarianism and the anxieties of an increasingly unstable world.

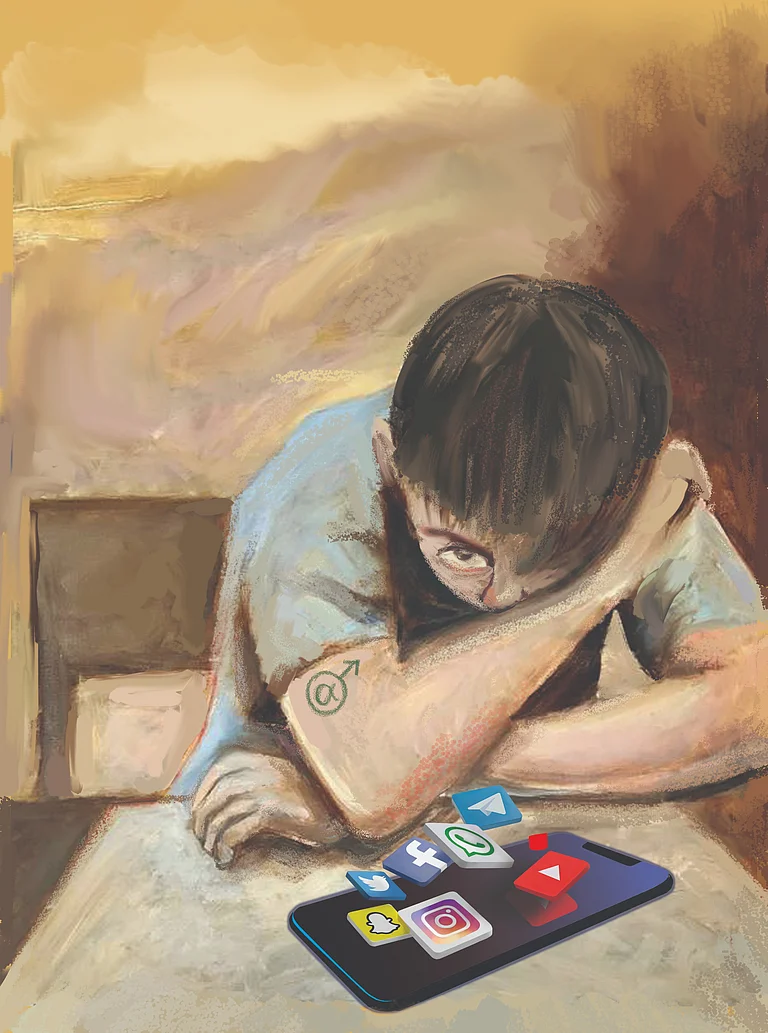

Instagram accounts devoted to Freudian theory have gathered nearly 1.5 million followers, while television programmes such as Orna Guralnik’s Couples Therapy have become compulsive viewing.

Think pieces in The New York Times, The London Review of Books, Harper’s, New Statesman, The Guardian and Vulture are proclaiming a renaissance for the discipline. As Joseph Bernstein of the New York Times observed: “Sigmund Freud is enjoying something of a comeback.” For many, the renewed interest is unexpected. Over the past five decades, psychoanalysis — the intellectual movement and therapeutic method established by Sigmund Freud in Vienna in 1900 — has often been dismissed within scientific communities.

In the English-speaking world in particular, the ascent of behavioural psychology and the rapid expansion of the pharmaceutical industry relegated long-form talking therapies to the fringes.

Yet the global story is more nuanced. During Freud’s lifetime (1856–1939), 15 psychoanalytic institutes were founded worldwide, including in Norway, Palestine, South Africa and Japan. Across the 20th century, the field frequently flourished — from Paris to Buenos Aires, and from São Paulo to Tel Aviv.

In South America especially, psychoanalysis continues to exert strong clinical and cultural influence. In Argentina, its popularity is such that it is jokingly said one cannot board a flight to Buenos Aires without at least one analyst on board.

Several factors explain why psychoanalysis thrived in some regions but not others. One is the 20th-century history of the Jewish diaspora. As the Third Reich advanced, Jewish psychoanalysts and intellectuals fled central Europe ahead of the Holocaust.

Cities such as London, which received Freud and his family, were culturally transformed by this influx of refugees.

Another, less obvious factor relates to authoritarianism. Though psychoanalysis emerged amid the upheavals of wartime Europe, its appeal has often intensified during periods of political crisis.

Consider Argentina. As left-wing authoritarian Peronism gave way to a US-backed “dirty war”, paramilitary death squads abducted, killed or “disappeared” an estimated 30,000 activists, journalists, trade unionists and dissidents.

Grief, fear and enforced silence permeated everyday life.

At the same time, psychoanalysis — with its focus on trauma, repression, mourning and the unconscious — offered a way to confront oppression. Therapeutic spaces for articulating loss and trauma became a means of responding to, and at times resisting, political catastrophe.

In a culture defined by official falsehoods and imposed silence, speaking openly became an act of defiance.

Many of Freud’s early followers had employed psychoanalysis in a comparable fashion. Confronted with the horrors of European fascism, figures such as Wilhelm Reich, Otto Fenichel, Theodor Adorno and Erich Fromm combined psychoanalysis with Marxist thought to examine how authoritarian personalities are formed and sustained.

In Algeria, psychiatrist and anti-colonial activist Frantz Fanon drew extensively on psychoanalytic ideas in challenging the racial hierarchies of French colonialism. For these thinkers, psychoanalysis was intertwined with political resistance.

A similar pattern may be emerging today. As new forms of multinational autocracy consolidate power, migrants are vilified and detained, and violence is broadcast in real time, psychoanalysis is once again gaining traction.

A tool for making sense of the senseless

For some advocates, neuropsychoanalysts such as Mark Solms have helped bridge the gap between psychoanalysis and contemporary neuroscience. In his recent book, The Only Cure: Freud and the Neuroscience of Mental Healing, Solms draws on research into dreaming to contend that Freud’s theory of the unconscious was fundamentally correct.

Solms argues that while medication can offer temporary relief, it provides only short-term solutions; by contrast, psychoanalytic treatment yields enduring change.

He is one among a broader group of clinician-intellectuals contributing to the field’s renewed prominence. Where Solms leans towards neurology, others — including Jamieson Webster, Patricia Gherovici, Avgi Saketopoulou and Lara Sheehi — foreground psychoanalysis’s political dimension.

Their work suggests that key concepts such as the unconscious, the “death drive”, universal bisexuality, narcissism, the ego and repression illuminate aspects of the contemporary moment that other frameworks struggle to explain.

In an era marked by commodification, psychoanalysis resists purely market-driven notions of value. It insists on slow, sustained attention in a culture of shrinking attention spans, and upholds the importance of creativity and human connection amid rapid advances in artificial intelligence.

It also challenges dominant ideas about gender and sexuality, while centring individual experiences of suffering and desire.

The forces driving psychoanalysis’s present revival resemble those that propelled earlier waves of interest. During times of upheaval, state violence and collective trauma, it offers conceptual tools for understanding what otherwise appears incomprehensible.

It provides a lens through which to examine how authoritarian tendencies take hold within individuals and proliferate across societies.

Moreover, in a mental health landscape dominated by quick fixes and pharmaceutical solutions, psychoanalysis champions careful engagement with psychological complexity. It resists reducing distress to chemical imbalance or treating symptoms in isolation, instead approaching each person’s inner world as deserving of thorough exploration.

This resurgence is also prompting internal change within the field. Long-standing assumptions — including the expectation of therapist neutrality or the privileging of heterosexual norms — are being questioned. Psychoanalytic practice is increasingly engaging with movements for social justice and solidarity.

Whether this revival will prove lasting remains uncertain. For now, however, amid mounting political crises and dissatisfaction with conventional therapeutic models, Freud’s insights into the human psyche are resonating with a new generation seeking to understand the anxieties of the present.

(with inputs from The Conversation and PTI)