Summary of this article

Decades of grief have settled quietly into women’s bodies, and silences.

Most women sought help late, often after years of turning to faith and endurance.

It is their adult children who are now recognising the signs and pushing families toward care.

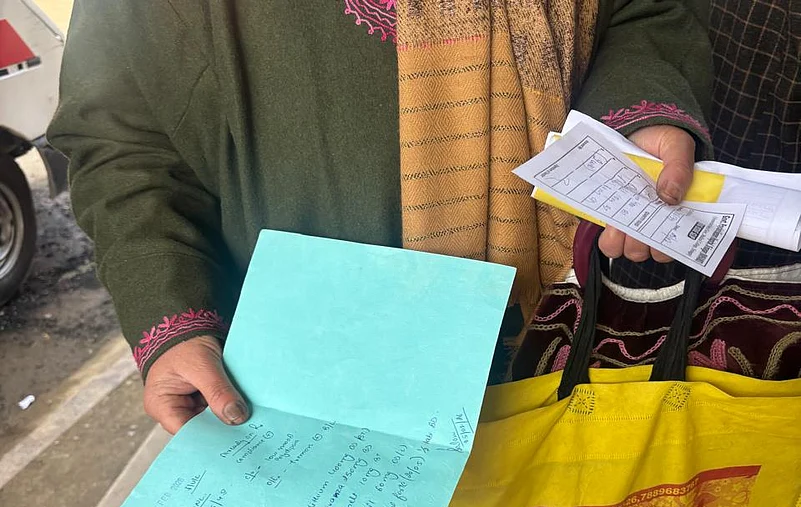

In a quieter corner of the market, away from the crowds and chatter, Shamima rests with a black burka drawn close around her shoulders. She is far from courtrooms and traffic. At 66, she moves through her day, her hands trembling in her lap.

The death of her husband years earlier had left the household unsettled, but she endured. When her son, who also worked in their copper workshop and was the keeper of their family craft, died too, the loss was devastating.

The workshop, once alive with the steady hammering of metal and the gleam of samovars, fell silent.

Shamima, who had always been part of the work, was left with an emptiness. For some time, she clung to her daily structure. She cooked, swept, maintained the house, visited neighbours. But slowly, though, the fractures appeared as names slipped from memory. Then tools were misplaced. And bills went unpaid. Soon, familiar faces blurred into strangers. Thus, the world she had once navigated with certainty began to recede.

“Sickness took over me,” she murmurs. “I went mad.”

She turned to faith healers, travelling from village to village, paying what she could, submitting herself to rituals in dim rooms thick with incense and promise. Years passed this way, but relief never came.

When she finally reached doctors, the diagnosis was blunt: Long-term grief had hardened into cognitive decline, anxiety, and depression. Her trembling hands were not signs of age alone. They were the body’s record of decades of unprocessed sorrow. Her treatment began late and cautiously when much damage had already settled in.

The burka shields her from the world’s gaze, concealing the tremor, the unsteady gait. It’s both protection and withdrawal. And yet, when she speaks of the past, her voice changes. She remembers the samovars they made. The weight of copper, the satisfaction of a flawless finish, and the dignity of work shared.

Across the region, many women have carried similar burdens, absorbing grief quietly, seeking help late, and surviving long after the world has stopped paying attention.

The Weight Of Hidden Distress

The waiting area at Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (IMHANS) Srinagar is crowded. Women in burkas, scarves, and shawls clutch medical files or hold the hands of elderly relatives. The hum of conversation mixes with the shuffling of slippers on the tiled floor. Each person carries a story and a hidden weight.

The scale of that distress became visible in 2016, when Médecins Sans Frontières, in collaboration with IMHANS Srinagar, conducted one of the largest mental health surveys in the region, revealing that nearly 45 per cent of adults showed symptoms of mental distress, with significant proportions reporting depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Women were particularly affected, and for many families, the figures merely confirmed what had long been normalised.

On a typical day, around 300 to 400 patients receive treatment at the Outpatient Department (OPD). Statistics show that in 2024, a total of 2.03 lakh patients were examined at IMHANS Srinagar’s OPD, with nearly 2,000 admitted to the hospital.

The 2016 survey also traced a sharp rise in weekly OPD registrations, from 100 in 1980 to 850 in 2016, reflecting the mental health toll after the rise of militancy post-1989.

Walking through the corridors, the sheer number of people waiting, some silent, some fidgeting, some softly praying, underscores what numbers alone cannot capture. For many women, survival has long been the only available goal, and only now are signs of long-term psychological injury being formally recognised.

Kupwara: A Life Of Quiet Strain

Long-term trauma in women often does not announce itself with dramatic breakdowns. It settles into routines, quiet withdrawal, and subtle physical symptoms that can go unnoticed for decades, says clinical psychologist Aiman Rafiq, who works with Shamima and women like her.

In a village in Kupwara, a woman in her fifties lost her husband many years ago. She immediately took on the responsibility of keeping her household functional, raising three children alone, cooking, cleaning, and maintaining the home with quiet diligence. From the outside, she appeared strong, unshakable even, but inside, her distress crept silently, in ways her family struggled to understand.

She would spend hours in the washroom. Sometimes five at a stretch. Unresponsive to calls, skipping meals, retreating into silence. At first, her children thought she was stubborn or forgetful. She faced lot of ridicule.

Five hours in the washroom? the family would ask, half irritated, half confused.

They did not know these “sacred hours” were when her mind was processing decades of grief and relentless responsibility.

It wasn’t until her children had grown and could look beyond the daily routine that they realised something more serious was happening. Gently, they persuaded her to see a mental health professional. Years of unacknowledged grief, finally, began to be visible.

Another woman, also in her fifties, grew up in a world shaped by violence. In the 1990s, her brother was beaten in front of her during a cordon-and-search operation, leaving him partially disabled. She carried that trauma silently, but her body reflected the unease she could not name. Chronic insomnia, anxiety that tightened her chest. Doctors treated her heart, stomach related ailments but nobody asked about the fear that never left her mind.

It was her grown up children who recognised the toll, understanding that her restlessness and routines were the body’s record of years of fear. The process of healing has been slow, but layers of trauma are beginning to be understood, say experts.

“When younger generations step in with awareness and support, it can make a real difference,” says veteran psychologist Dr Mushtaq Margoob. “Faith and spirituality can provide resilience, but only when practiced thoughtfully and alongside professional care.”

Endurance At A Cost

For decades, the invisible weight of trauma in Kashmiri women was carried alone. Clinical psychologist Zoya Mir, founder of Psychlite, describes the deeply gendered nature of this endurance: “Women are socialised to carry suffering quietly. They absorb violence that never touched them directly and perform caregiving as if their own pain is irrelevant. This is praised as strength. In reality, it’s an unpaid, unrecognised emotional labour that extracts a long-term psychological cost.”

Often, when women finally reach clinics, they do not arrive saying they are anxious or depressed. Emotional suffering was unacceptable, so the body carried it. By the time psychiatric care began, the damage was already deep.

Access to specialised mental health care is limited, particularly in villages and smaller towns. Women rely on faith healers, rituals, and self-medication because these are accessible and socially acceptable.

“Seeking psychiatric help exposes women to scrutiny,” Mir explains. “Hospitals mean travel, questions, judgment. Faith healers offer containment, not cure. So women oscillate between both, without sustained support.”

Tele-MANAS, a helpline run by the Government Psychiatric Hospital, has become a lifeline. Senior consultant Dr Muhammad Abrar Guroo says the helpline receives nearly 150 distress calls a day, many from women.

“The helpline has become important because it offers anonymity. Women can speak without being seen, without travelling, without explaining themselves to family members or neighbours. For many women, especially in rural areas, this is the first time they are speaking to a mental health professional. They may never reach a hospital, but they will pick up the phone. While trauma cannot be erased, what treatment can do is help people live with it without collapsing.”

What has begun to shift is not the past, but the vocabulary around it as adult children are increasingly noticing symptoms in their mothers, like hours spent alone, refusal to travel, sudden bursts of anger, tremors that worsen in winter, says Rafiq. “They come to us saying, ‘My mother hasn’t slept properly in years,’ or ‘She keeps replaying old incidents’,” says Rafiq. “The mothers themselves often say this is just how life is.”

“In Kashmir, women have learned survival, not healing. Loss cannot be undone or reversed through medication alone. But naming distress as trauma, rather than personal failure, shifts the weight slightly,” Mir says.

Mir says: “Women are taught that endurance is virtue. If they don’t collapse, we assume they’re coping. But what we are really seeing is sustained emotional labour. They are absorbing loss after loss without ever being given space to process it.”

As Shamima sits again in her courtyard, prayer beads slipping slowly through her trembling fingers. Nothing can back her son, or steady her hands overnight. But it gives her suffering a name. “It seems that the treatment is working,” she says.

Dr Junaid Nabi, Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Government Medical College Srinagar (IMHANS-K), says: “Trauma cannot be erased, but resilience can be built. Even thought, it’s very hard to tell someone who has lost a loved one that it’s okay. But they learn to live with the loss, but it never disappears.”