Summary of this article

Accompanists in Indian classical music often face low pay, backstage discrimination, and lack of recognition.

Prominent main artists can improve conditions by insisting on fair treatment and proper accommodation for their co-artists.

Despite improvements, challenges like gender bias, publicity neglect, and inadequate travel arrangements persist.

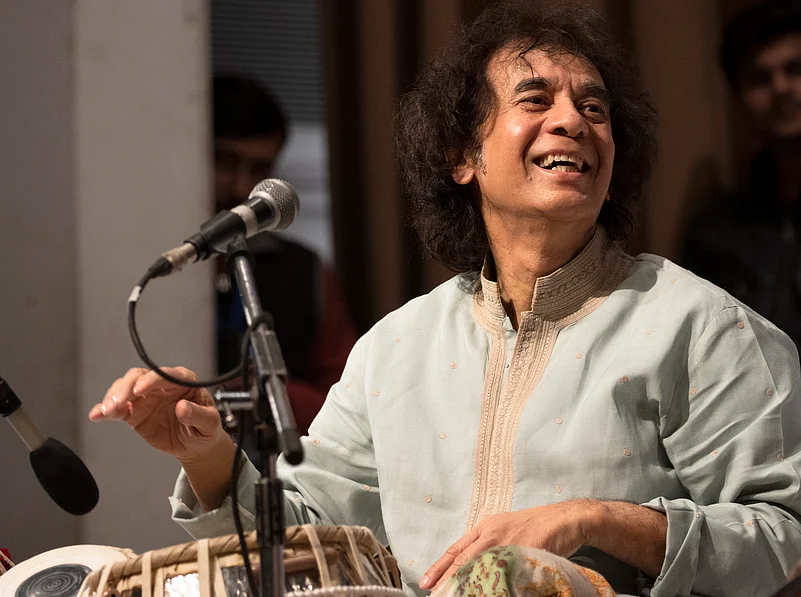

Many years ago, the iconic Ustad Zakir Hussain, arguably the most influential musician in India for the last fifty years, was commissioned to accompany a senior instrumentalist at the house of an industrialist in Mumbai. When he arrived, he was guided to the servants' entrance and asked to wait with them till the concert commenced. After the concert, he was again led to the back entrance to eat with the servants. Of course, the leading artist was not subjected to these slights.

Zakir, at the time, had not become the phenomenon he became. However, he was still the son of the great Ustad Alla Rakha, one of the triumvirate of great tabla players, along with Pt Samta Prasad and Pt Kishan Maharaj.

Zakir was not singled out for this treatment; this discrimination was an accepted part of the world of classical music, North and South. It compelled curator Mala Sekhri to add a session on accompanists to the recently concluded India Music retreat in Jaipur, called ‘Song of the unsung’. Sekhri shared, "In the twenty-five years I have been involved with music, I have seen how these artists have stayed in the shadows.”

Proportionately, the fees of accompanyists are very low, usually not even ten per cent of what the main artist commands. Santoor maestro, late Pt Shiv Kumar Sharma, and vocalist late Pt Jasraj were initially trained as tabla players but switched early on in their careers as they realised how different the stakes were.

While it is easy to blame rapacious organisers for the low remuneration rates, one wonders why the leading artists don’t put their foot down? There are very few main artists who insist on proportionate fees for their accompanists; usually, a package deal is negotiated, and the main artist himself gives a tiny remuneration to the accompanist. Young Kolkata-based tabla exponent Debjit Patitundi rued, “We too have families to support from our art, which is our profession.”

The fairest way is for the leading artist to insist on his accompanists and then request the organiser to negotiate terms with them directly. Ustad Murad Ali Khan, an acclaimed sarangi maestro and one of the most popular accompanists today, shared that the status of co-artists (he prefers the term "accompanist") has improved in the last twenty-five years. It’s the prominent artists who have brought about this change, at least in my case, he says. From Vidushi Shubha Mudgal to late Ustad Rashid Khan to Kaushiki Chakraborty, the artists he mainly accompanies, everyone has insisted on their accompanists being treated with overt respect.

The popular duo of Pts Rajan Sajan Mishra from the Banaras gharana at the start of their careers decided to become singers, even though many in their family were acclaimed accompanists. They realised that it was not the level of their art but the manner in which accompanists are treated. Pt Sajan Mishra shared, “Fifty years ago, things were different. Fees were very low, too. My brother and I have always tried to insist on the same accommodation for our ‘sangatkaars’ (the very word means in alliance with). Today, I feel things have improved. It also depends on the status of the accompanist, how much of a name you have, how popular you are.”

Whilst things have improved in the last twenty years, still much is left that needs change.

Expecting accompanists to share a room is another horrifying aspect of an accompanist's life. Usually, the younger artists are forced to share, with the organisers excusing themselves as they stay in an expensive five-star hotel. Apart from the indignity of sharing a room with a stranger, there are the more practical needs an artist faces, such as doing ‘riyaaz’ at night, being one. An artist is expected to be more sensitive than a non-artist. In addition, the average performing artist has trained diligently for a minimum of four hours a day for at least eight years before he ascends the stage; private space is the very least he can expect when on the road. Again, it’s the prominent artists who need to insist that their team’s stay is with dignity. Pre-concert rehearsals are a necessity, necessitating the same hotel stays.

Every artist is trained to play solo, and accompanists are, in addition, taught the art of being a ‘sangitkaar’. Whilst most top-level accompanists are themselves masters and soloists when the opportunity arises, when they are hired as accompanists, they have to fight for parity. Until a few years ago, organisers would try to pay only train fares, not airfares. With the number of concerts happening today, mercifully, that is no longer an option; no one has the time to waste a day on train travel. Organiser’s petty miserliness even extends to trying to book small cars for outstation travel, as these are cheaper than the big SUVs. However, the space for luggage is abysmal and frequently instruments are precariously squeezed in between seats and floor area.

Publicity material circulated before a concert usually focuses only on the main artists. A commonly heard excuse is the lack of space to add accompanists’ names or photos; a more relatable reason is the incomprehension of most organisers about the importance of the accompanist. They don’t understand that to a music lover, it matters who is accompanying whom; it adds value to the concert. Organisers in Kolkata and Mumbai seem to be more sensitive in this respect, with videos, posters, and cards including photos and names of the co-artists.

It is the same in the world of Carnatic music, with an additional gender bias being thrown in. Until a few years ago, many established accompanists of the older generation used to refuse to accompany lady singers. Vidushi S Sowmya, incidentally a recipient of the highest accolade given to a Carnatic musician, the Sangita Kalanidhi award, mentioned an incident when a senior mridangam artist refused to accompany her at a prestigious concert. Years later, when she was travelling to the US, the same senior approached the organiser requesting a concert with her. Still, Sowmya refused, laughingly saying she had got used to her usual team of accompanists.

Unless popular main artists insist on the same rights and privileges for their co-artists, accompanists will continue to be demeaned. It is not enough to feel that a lot has changed in the last thirty years.