Summary of this article

From childhood daydreams to adult reflection, the author explores “elsewhereness” as a powerful human impulse—the longing for a place that is always distant, imagined, or just out of reach, and therefore eternally alluring.

Elsewhereness becomes a literary and political tool, allowing poets and writers—from Swift to Wordsworth—to critique reality indirectly, revealing deeper truths through metaphor, landscape, and silence rather than overt argument.

As imagination gives way to travel, experiences become stored as future nostalgia—painful yet beautiful memories that offer emotional refuge and insight, enriching everyday life and deepening the understanding of longing itself.

I often feigned illness on Monday mornings to avoid a needlework class in school. As soon as the school bus had trundled down the street, however, it was safe to be well again. I remember lying back in bed, looking out at a peepul tree, and dreaming my way into ancient Greece.

As a seven-year-old in Mumbai, I knew absolutely nothing about ancient Greece. But I did know that the seas would be bluer than any I’d seen. The skies would be more azure, the olive groves more mysterious. And the sound of Orpheus’ lute wafting across goat tracks and forested valleys would be magical.

How did I know that? Because, like every other kid, I understood elsewhereness. No flight, train, or boat could ever take me there. And if they did, I knew I’d want to be right back here—on this bed, looking out at the same peepul tree. The crux of elsewhereness was that it was always—well, elsewhere. Once you got there, it was always someplace else. That’s what made it so special.

Years later, I wrote a poem that started with the line, “Give me a home that isn’t mine.” By then, I knew that what I wanted was a home that spelt familiarity and strangeness, anchorage and adventure, security and freedom. I wanted both. And, of course, that meant a life of perennial oscillation—between travel and return, exploration and withdrawal, advance and retreat. To be human, it seemed, was to swing between two seductive polarities.

Later, I found elsewhereness had its political uses. I found that an 18th-century writer like Jonathan Swift could speak of a place called Lilliput to make scathing references to the England he lived in. Elsewhereness was a way to tell veiled truths, knowing full well that the veil revealed more than it concealed.

A poet like Wordsworth could speak, I found, of pastoral landscapes to make an oblique statement about industrialisation and moral decline. A poet like Frost could speak of the dense forests of New England to make a statement about mechanisation and modernisation. It wasn’t what they said. It was what they didn’t say that made their critique devastating.

Poetry was about challenging tired journalistic cliches, cutting through academic abstractions.

Poets didn’t make us escapist, Aristotle reminded us. They offered us truth over fact, a parallel reality that healed and transmuted us, and made us better able to deal with this reality. I began to see what he meant.

As a young poet, I wrote a poem about a childhood vacation in Delhi to explore the theme of religious difference. I’d begun to realise I didn’t have to use terms like ‘communalism’ and ‘inequality’ to be topical. Poetry was about challenging tired journalistic cliches, cutting through academic abstractions. It was about making generalities less smoky, grainier. By breathing life into another moment, you tried to hold up a mirror to the world you inhabited.

Still later, I turned from dreamer to traveller. I began to understand what Vikram Seth meant when he said that he wandered the world to merely accumulate “material for future nostalgias.” Once I’d been to a place, it entered the hard disk of memory, and the file could be opened up when needed. In the middle of a Mumbai workday, I could think back on the time spent in Ramana Maharishi’s ashram in Tiruvannamalai, and feel a pang of longing. That longing was painful. But it was also exquisite.

Looking out at a grimy Arabian Sea, I could think wistfully of Florence, and be transported instantly to a bridge along the River Arno. I could conjure it in vivid detail – the angle of sunshine on the water, the distant cry of peddlers on the Ponte Vechhio, the loneliness of my walk down the riverbank. Nostalgia made the loneliness more intense. But it also made it more delicious.

And then, elsewhereness changed its colours yet again.

It turned from daydream, political strategy and nostalgia into something else. It became raw, urgent, disruptive. It was no longer mellow sentimentality. It became a roaring appetite for something more. A great churning. A pain born of some nameless sense of severance.

What Was that Severance About?

I didn’t know. But I did know that the old stories—Muruga taking off on his journey around the world on his peacock, Ulysses’ ten-year journey back to Ithaca after the Trojan War, the rebellious Prodigal Son leaving home—meant something more than I’d imagined. There was an existential homesickness that these characters pointed to. As they travelled, they seemed to be enacting a pilgrimage to some ancient elsewhereness. Every detour, they suggested, could be just another way home. And as I blundered through my own life, I realised I was, in my own unheroic way, following in their footsteps.

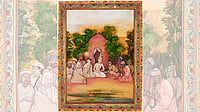

In 2003, I found myself in a Guwahati hotel room, thinking, for some reason, of Shakuntala (the Sanskrit playwright Kalidasa’s heroine), preparing to leave her forest hermitage. The thought filled me with a tremendous unexplained grief. It is a poignant scene in the play, but I now experienced it as sheer heartbreak. Shakuntala had become, for me, a figure doomed to endlessly conflicting needs: between forest and court, nature and culture, flesh and spirit, earth and sky. My ache wasn’t as personal as I’d believed. I realised I was instead logging into an elemental longing, something as primal as the River Brahmaputra outside my hotel window.

Elsewhereness now wasn’t about a restless mind entertaining itself with its own nostalgias. It was born of a need to address a much deeper wound. Elsewhere was no longer a reprieve from home. Elsewhere was home. Or at least an indispensable part of it.

The writer Albert Camus spoke of the “human cry confronted by the unreasonable silence of the world.” The human cry is unoriginal. But it still cannot be quelled. And so, each one of us, at some point, wakes up to it. We roar into the night. We shake a fist at the heavens. We bay at the moon. We want home—and we want it now.

True longing alchemises us. As the experience of incompleteness eats into our innards, it births us, gradually, into a new wholeness.

The only ones who understood this ‘cry’ inside out, I discovered, were the mystic poets. They seemed to know something about befriending the night. They told me that being greedy for someplace else wasn’t escapism. It was a vital, transformative greed. The 12th-century mystic poet, Akka Mahadevi, surely knew it when she spoke of “the Brahman hiding in yearning.” The 17th-century poet, Tukaram, knew it when he said, “When he comes out of the blue, a meteorite shattering your home, be sure god is visiting you.” And the15th-century poet, Annamacharya, knew it when he described a woman’s yearning for her lover: “She’s thinking so much, and missing him/ that when he comes to her door and calls her,/ she doesn’t hear…/He’s standing right next to her.”

Many view these poets as sentimentalists. They seem juvenile enough to dream about gods with names, forms, addresses. And they seem naïve enough to believe that their songs will win them visas to these divine homelands—whether they call them Vaikunth, Kailasa, Jannat, Paradise, or Begumpura.

But I gradually began to understand something about the need for these imaginary homes. As these poets named their longing, they turned a passive longing into dynamic desire. They turned apathetic waiting into alert listening. They turned projection into presence. They began to be scorched in the fire of their own yearning. That fire cauterised them, remade them. They began to sing themselves home.

The greatest stories of the world tell us we can never return to the home that we left. Not because the zip code is different. But because we are. The weary traveller, the wounded warrior, the thirsty lover have been remade by the journey. And so home—however pastoral, serene, unsullied—is remade too. Irrevocably.

In poet Jayadeva’s lyrical-erotic 12th-century work, the Gita Govinda, Radha and Krishna—human and divine, traveller and destination—are both transfigured by love. Their place of union is neither their natal nor marital home. It makes for a new place altogether. A new address. A brand-new residence. Not where we are. Not someplace else. It is, instead, where innocence meets experience. Where body meets beyond. Wilderness meets home. Woman meets man. And neither will ever be the same again.

True longing alchemises us. As the experience of incompleteness eats into our innards, it births us, gradually, into a new wholeness. And one day, it would seem, we no longer see any conflict between earth and sky, now and forever. The divide has been healed. We are home. Elsewhere is right here.

Home

Give me a home

that isn’t mine,

where I can slip in and out of rooms

without a trace,

never worrying about the plumbing,

the colour of the curtains,

the cacophony of books by the bedside.

A home that I can wear lightly,

where the rooms aren’t clogged

with yesterday’s conversations,

where the self doesn’t bloat

to fill in the crevices.

A home, like this body,

so alien when I try to belong,

so hospitable

when I decide I’m just visiting.

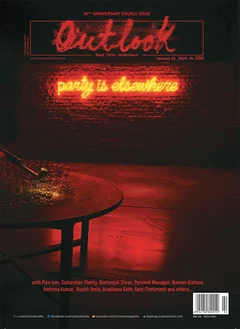

This article appeared as ‘Elsewhere” in Outlook’s 30th anniversary double issue ‘Party is Elsewhere’ dated January 21st, 2025, which explores the subject of imagined spaces as tools of resistance and politics.

(from Arundhathi Subramaniam’s Where I Live: New and Selected Poems, Bloodaxe Books, 2009)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Arundhathi Subramaniam is the author of 15 books of poetry and prose. Her recent work includes the poetry collection The Gallery of Upside Down Women and the book of essays, Women Who Wear Only Themselves. She is the winner of several honours, including the Sahitya Akademi Prize for Poetry, the Il Ceppo Prize in Italy, the Mahakavi Kanhaiyalal Sethia Award and the inaugural Khushwant Singh Prize for Poetry