László Krasznahorkai wins the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature for his haunting, apocalyptic vision.

His works transform despair, decay, and silence into moral and artistic revelation.

The Nobel honours a writer who turns ruin into witness and darkness into defiant hope.

The Nobel Prize in Literature has long been the highest affirmation of humanity’s faith in the written word, a recognition that literature, at its finest, is both conscience and compass. Each year, its announcement renews belief in the moral and imaginative power of art to reveal what history conceals. When the Swedish Academy named László Krasznahorkai, the Hungarian novelist, as the 2025 Laureate, the choice once again drew our gaze toward the darker half of the world, where words still dare to wrest meaning from despair.

The citation praised him ‘for his compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art.’ Yet, this is no triumphal fanfare. It feels like a whisper from the ruins, a reckoning more than a celebration.

Born in Gyula in 1954, in a Hungary still learning to breathe after its long suffocation under history, Krasznahorkai has spent his life listening to the faint sounds that survive after catastrophe. His fiction carries the texture of decay, the slow crumble of certainty, the dust of exhausted faith. His sentences, long and circling, move like prayers spoken underwater: breathless, weighty, and strangely luminous.

In Sátántangó, The Melancholy of Resistance and War & War, he dismantles the illusion of progress and uncovers beneath it a wounded, stubborn beauty, the beauty of persistence itself.

Susan Sontag once called him ‘the master of apocalypse.’ It was not flattery but recognition. For Krasznahorkai, apocalypse is not an event; it is a condition—a slow corrosion of meaning that only art can make visible.

Through his collaborations with filmmaker Béla Tarr, his words became images: long, meditative takes where silence grows into speech and light itself learns to hesitate.

The Nobel, then, is not a crown but a candle, its flame trembling before the wind, yet refusing to go out.

Krasznahorkai’s prose does not invite; it demands. It refuses comfort, consolation, and all the small distractions of contemporary reading. It asks the reader to endure slowness, to inhabit despair long enough to glimpse its hidden music.

In a time addicted to haste and surface, his work arrives like an ancient storm, unhurried, inevitable, moral. He belongs to that rare fraternity of writers, Kafka, Bernhard, and perhaps Beckett, who turned the sickness of modern life into a strange kind of prayer. Yet his imagination remains unmistakably his own: born in the fog of Central Europe, but wandering restlessly through Japan, China, and the metaphysical deserts of the world.

His apocalypse is not of one country or creed, it is the apocalypse of humanity itself: banal, bureaucratic, absurd, and heartbreakingly ordinary.

It has been more than two decades since Imre Kertész received the Nobel (2002). Between these two Hungarian writers stretches a long silence, an age of disillusionment where art survived by whispering, not shouting. By honouring Krasznahorkai, the Academy has honoured that silence, that patience which learns to speak through ruin.

Why now? Because the world, once again, has come to resemble his pages.

Everywhere there are small tyrannies tightening their grip, borders of empathy shrinking, forests and languages vanishing into oblivion. The climate itself has grown impatient, no longer willing to wait for our repentance. In such a world, literature that dares to be slow, difficult, and unsparing feels like a moral necessity.

The Academy’s words, ‘in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art’ sound almost like a confession. Perhaps, unknowingly, they also offer a command: Do not look away.

Krasznahorkai reminds us that to truly witness despair is itself an act of defiance, and that to continue writing within darkness is the oldest form of hope.

In India, the announcement passed through literary circles with the usual curiosity: ‘Who were the contenders? Was there an Indian nomination?’ But the truth remains cloaked: Nobel nominations are sealed for 50 years. What we discuss are shadows, not names.

Still, familiar names return each year, Amitav Ghosh, Salman Rushdie, Vinod Kumar Shukla, Uday Prakash, Arundhati Roy, writers whose imaginations have reached far beyond geography. And yet, more than a century after Rabindranath Tagore (1913), no Indian writer has held the prize again.

This absence says less about our literature, perhaps, and more about the hierarchies of global attention. But the answer cannot be to write for the Nobel. It must be to write beyond it, to create as if the prize never existed, as if the only prize were truth, or tenderness, or language itself refusing silence.

For publishers and translators, the Nobel will reopen doors long shut. Out-of-print titles will return. New readers, unprepared but curious, will arrive. Some will be bewildered; a few, transformed.

For Indian readers, Krasznahorkai offers not escape but companionship, a fellowship in darkness. In his world, despair is not surrender; it is awareness. To read him is to realise that bearing witness, without distraction, without turning away, is a political act.

We, too, inhabit our own apocalypse: disappearing rivers, rewritten histories, and an increasing silence where words once lived. In such a world, Krasznahorkai’s Nobel is not an accolade but a reminder: to look harder, stay longer, and refuse to forget.

The Nobel will give him a medal, some money, and a winter evening in Stockholm. But its true gift is something quieter, the widening of attention, the small, miraculous crossing of languages.

Perhaps, somewhere in a small Indian town, a reader will open Sátántangó, find its first, endless sentence, and recognise in its rhythm their own time, their own fear, their own fragile persistence.

Krasznahorkai writes about endings. Yet, his sentences never end; they bend, circle, and begin again, like the stubborn breath of life itself. In that endlessness lies his faith: that even in the ruins of meaning, language can still build a shelter and call it hope.

views expressed are personal.

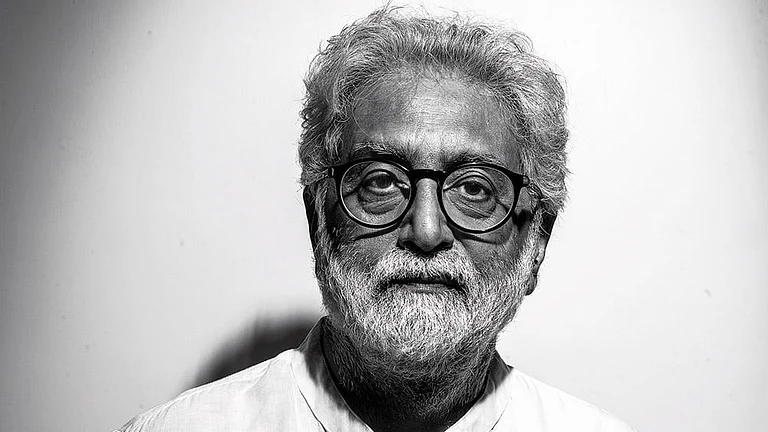

Ashutosh Kumar Thakur is a management professional, literary critic, and curator based in Bangalore.