Summary of this article

Flesh follows István, a Hungarian immigrant, from awkward teen to middle-aged man, exploring life, desire, and survival.

Szalay’s minimalist style leaves readers to interpret character emotions and moral choices, making it deeply immersive.

The novel examines modern European society, class divides, and male identity through decades of István’s journey.

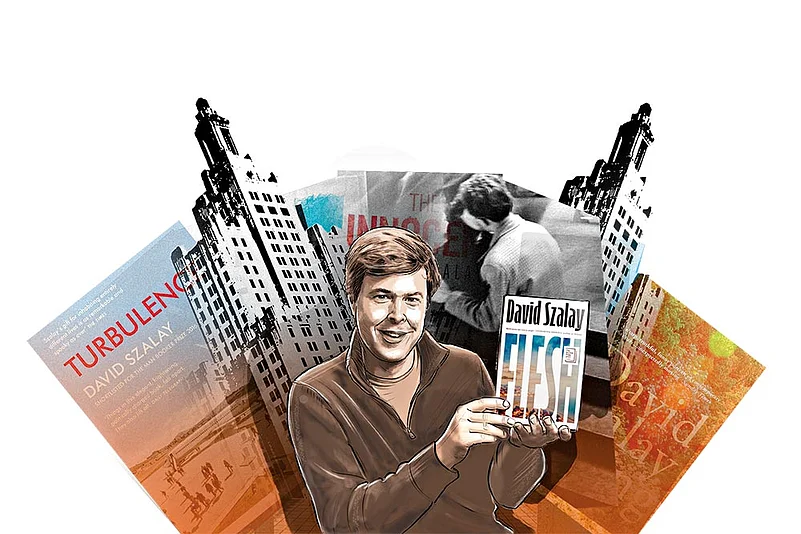

Critics like to call Hungarian-British author David Szalay ‘a writers’ writer’. On being awarded the 2025 Booker Prize for his novel Flesh, Szalay said that he had wanted “to write about life as a physical experience, about what it’s like to be a living body in the world.” The body in question in Flesh is that of István, a working-class Hungarian immigrant who struggles to find his footing in a fast-changing Europe. This is a ‘risky’ novel in terms of both style and theme.

Over the last 16 years, Szalay’s books have been mapping the contours of masculinity in the contemporary world. They trace the lives of men on the move, outsiders navigating alien environments, ‘in-between people’ who don’t belong to any one place. Flesh is his sixth work of fiction. His debut novel, London and the South-East (2009), won critical acclaim and was awarded the Betty Trask and Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prizes. In 2016, his book All That Man Is, made it to the Booker shortlist. Many of Szalay’s characters are everyday men. The hero of London and the South-East slogs in tele-sales. Spring (2012) tells the story of James—an entrepreneur who struggles after the dotcom bubble goes bust. All That Man Is follows nine men of different ages, each weighed down by their own existential dilemmas.

Flesh begins when István, the protagonist, is a socially awkward teenager. He has trouble making friends at school. His life is confined to a council estate in a small Hungarian town where he lives with his mother. István is no conversationalist. His vocabulary is pretty much limited to ‘yeah’ and ‘okay’. When his neighbour, a married woman in her 40s, shows an interest (of the carnal kind) in him, István’s life changes beyond recognition. The narrative traces István’s encounters with her which leave him confused as well as curious; a violent act that forces him to spend time in a correctional facility; his stint in Iraq after he joins the army; his move to London and up the food chain; his journey from rags to riches and back to rags; his transition from boyhood to adulthood to middle age during a tumultuous time in Hungary’s history.

Adept at raising questions, booker winner David Szalay steers clear of the temptation of handing out easy answers or nudging readers towards moral judgement.

This year’s Booker judging panel, chaired by Irish novelist and dramatist Roddy Doyle, considered 153 books before picking the winner. After picking the winner, the panel announced, “We had never read anything quite like it [Szalay’s Flesh]. It is a disquisition on the art of being alive, and all the affliction that comes with it...The pace of this novel speaks to one of the greater themes; the detachment of our bodies from our decisions.”

Szalay’s novel is a unique and original work of fiction. He makes some daring choices. Readers are not given a physical description of István. His life simply unfolds in front of readers as it happens; the author doesn’t explain his inner workings or motivations at any point. In a previous interview, Szalay said, “I very specifically didn’t want a character who unpacked themselves for the reader, either reliably or unreliably...” In the hands of a lesser writer, this would have spelt disaster. But Szalay succeeds at making readers care deeply about his hero and his travels across decades. The plot, with plenty of organically conceived twists and turns, keeps the momentum going.

Szalay captures the nuances—mundane, comforting, disquieting—of his characters’ experiences of inhabiting this world at a particular moment, of eating in particular restaurants, of walking down particular city streets, of feeling the rain on their skin, of making love, of wanting the warmth of another’s body. Desire stirs in István, but he doesn’t get to grasp its language fully. Things happen to István; he doesn’t make them happen. Forces beyond his control carry him forward and he drifts along, never finding the right words to express his feelings about what he’s going through.

The novel raises vital questions about modern life. These revolve around desire, money, sex, love, work. Around survival. Around the class divide, the chasm between Europe’s rich and poor. Adept at raising questions, Szalay steers clear of the temptation of handing out easy answers or nudging readers towards moral judgement. István’s life unravels in pared-to-the-bone prose. Readers are free to decide for themselves who to root for in the novel and who to reject; who to judge and for what reasons; to sense what is left unsaid, to fill in the gaps. Szalay’s spare style is a sledgehammer. The emotional blows it delivers are devastating. Less, in the case of this novel, hurts more.

As a Hungarian immigrant in London, István works the jobs (doorman at a strip club, driver for a super-rich family, property developer) that come his way. As an object of desire—of his married neighbour in Hungary; of Helen, the wife of his London employer who he later marries and has a son with—he goes with the flow. He is a man numbed by the world’s swirling currents. His verbal responses to all of life’s blows—the end of his relationship with Helen, the loss of his son, his fall from grace in London and subsequent penury—remain ‘yeah’ and ‘okay’.

His mother stays a constant presence in his life all through, but their interactions remain emotionally distant. Their conversations, right from the time he is a schoolboy, end up circling the things they actually want to address. A sample:

“How’s school?” she asks.

“It’s fine,” he says.

“Your marks have slipped a bit.”

“Yeah?” he says.

“I’m just trying to understand,” she says. “Are you making friends?”

“Yeah.”

“Yeah?”

He nods, not looking at her.

“That’s good,” she says.

He isn’t sure if she believes him or not.

Szalay cleverly builds a pattern through repetition, underlying the point that István’s choices and desires across the years follow a path that is set early in life. His body is the conduit through which he responds to the world. Rooted in his flesh, he is perplexed by the distance between his physicality and his feelings. István may be a singular character, but he is also part of a specific tribe of men. Szalay had started work on his novel wanting it to be a description, “unflinching but also basically sympathetic, of what it’s like to inhabit a male body—or indeed to actually be a male body.” At this task, he has succeeded with flying colours.

Vineetha Mokkil is senior associate editor, Outlook. She is the author of the book A Happy Place and Other Stories.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

This article appeared as Fleshpoint in Outlook’s December 1, 2025 issue as 'The Burden of Bihar' which explores how the latest election results tell their own story of continuity and aspiration, and the new government inherits a mandate weighted with expectations. The issue reveals how politics, people, and power intersect in ways that shape who we are—and where we go next.