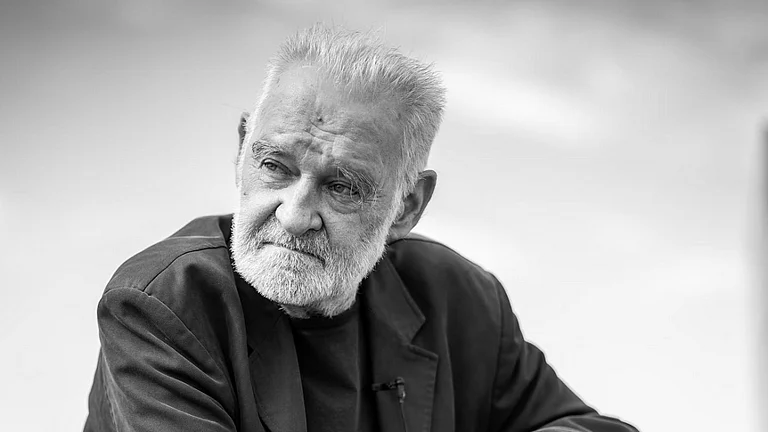

David Szalay wins the 2025 Booker Prize for his novel Flesh.

Szalay is the first author of Hungarian heritage to receive the prize.

Flesh traces the life of a Hungarian immigrant and is set in contemporary Europe.

David Szalay, who has been awarded the 2025 Booker Prize for his novel Flesh (Jonathan Cape), is the first author of Hungarian heritage to win the prize. Born in Canada, Szalay (51) grew up in London. He has lived in Hungary and is now based in Vienna. His mother is Canadian. His father, Hungarian. Over the last 16 years, Szalay has been chronicling the lives of men on the move, taking note of outsiders navigating alien environments, telling the tales of ‘in-between people’ who don’t belong to any one place.

Flesh is Szalay’s sixth work of fiction. Critics have been generous with praise since the Hungarian-British writer arrived on the scene with his debut novel London and the South-East (2009), which won the Betty Trask and Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prizes. In 2016, his book All That Man Is, made it to the Booker shortlist. It also received the Gordon Burn Prize and the Plimpton Prize for Fiction. Many of Szalay’s characters work ordinary jobs. The hero of London and the South-East slogs in tele-sales. Spring (2012) zooms in on James—an entrepreneur whose dotcom dreams crash and burn. All That Man Is follows nine men of different ages, each weighed down by their own existential dilemmas.

At the start of Flesh, István, the protagonist is 15. He lives with his mother on a council estate in a small Hungarian town. His vocabulary is pretty much limited to ‘yeah’ and ‘okay’. When his neighbour, a married woman in her 40s, shows an interest (of the carnal kind) in him, István’s life takes a whole new turn. The narrative traces István’s encounters with her which leave him confused as well as curious, a violent act that upends his world and lands him in jail, his army days, his move to London and up the food chain; his journey from rags to riches and back to rags; his transition from boyhood to adulthood to middle age during a tumultuous time in Hungary’s history. This year’s Booker judging panel, chaired by Irish novelist and dramatist Roddy Doyle, considered 153 books before picking the winner. In the end, when they had made up their minds, the judges announced, “We had never read anything quite like it [Szalay’s Flesh]. It is a disquisition on the art of being alive, and all the affliction that comes with it...The pace of this novel speaks to one of the greater themes; the detachment of our bodies from our decisions.”

Szalay uses ruthlessly spare prose to draw readers into István’s life. His sentences capture the nuances—mundane, comforting, disquieting—of the novel’s cast of characters’ experiences of inhabiting this world at a particular moment, of eating in particular restaurants, of walking down particular city streets, of feeling the rain on their skin, of making love, of wanting the warmth of another’s body. Desire stirs in István, but he doesn’t get to grasp its language fully. Things happen to István; he doesn’t make them happen. Forces beyond his control carry him forward and he drifts along, never finding the right words to express his feelings about what he’s going through.

Szalay avoids authorial commentary. He raises questions about modern life. These revolve around desire, money, sex, love, work. Around survival. Around the class divide, the chasm between Europe’s rich and poor. Though adept at raising questions, Szalay steers clear of the temptation of handing out answers or nudging readers towards moral judgement. István’s life plays out in pared-to-the-bone prose. Readers are free to decide for themselves who to root for in the novel and who to reject; who to judge and for what reason, to sense what is left unsaid, to fill in the gaps. Personally, I found Szalay’s spare style to be as powerful as a sledgehammer. The emotional blows it delivers are devastating. Less, in the case of this novel, hurts more.

As a Hungarian immigrant in London, István works the jobs (bouncer, driver for a rich family, property developer) that come his way. As an object of desire—of his married neighbour in Hungary; of Helen, the wife of his London employer who he later marries and has a son with—he goes with the flow. He is a man numbed by the world’s unpredictable currents. His verbal responses to all of life’s blows—the end of his relationship with Helen, the loss of his son, his fall from grace in London—remain ‘yeah’ and ‘okay’.

His mother is a constant presence in his life over the decades, but their interactions stay emotionally distant. Their conversations, right from the time he is a schoolboy, end up circling the things they actually want to address. A sample:

“How’s school?” she asks.

“It’s fine,” he says.

“Your marks have slipped a bit.”

“Yeah?” he says.

“I’m just trying to understand,” she says. “Are you making friends?”

“Yeah.”

“Yeah?”

He nods, not looking at her.

“That’s good,” she says.

He isn’t sure if she believes him or not.

Szalay cleverly builds a pattern through repetition, underlying the point that István’s choices and desires across the years follow a path that is set early in life. His body is the conduit through which he responds to the world. Rooted in his flesh, he is perplexed by the distance between his physicality and his feelings; between his desires and his decisions. István may be a singular character, but he is also part of a specific tribe of men. In a recent interview, Szalay shared that he had started work on the novel wanting it to be a description, “unflinching but also basically sympathetic, of what it’s like to inhabit a male body—or indeed to actually be a male body.”

At this task, he has succeeded with flying colours.