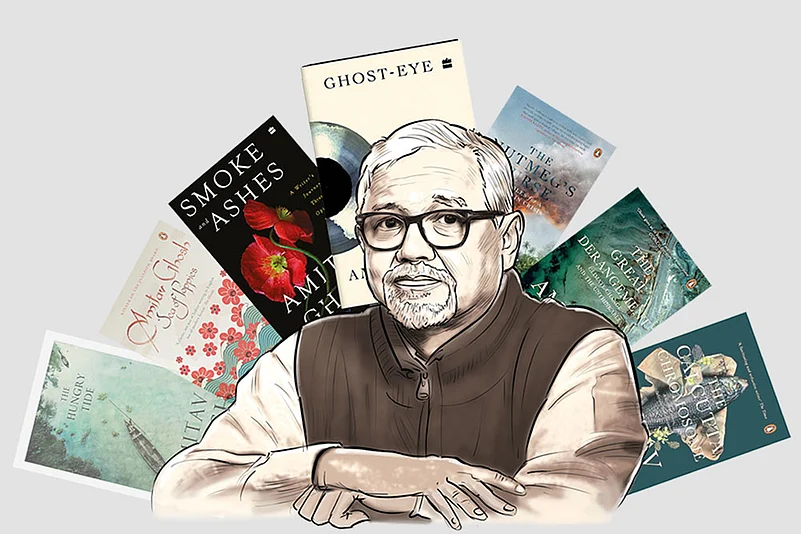

Amitav Ghosh’s new novel Ghost-Eye opens with three-year-old Varsha Gupta’s demand for fish. Born into a strict vegetarian Marwari family, she has never tasted fish or meat before. Her new dietary preferences and vivid memories of her past life trigger a storm in the Guptas’ mansion. The narrative flits between 1960s Calcutta, the Sunderbans and contemporary Brooklyn, grappling with many lives, many realities. Ghosh’s canvas is vast, encompassing the ‘environmental uncanny’ and ecological anxieties; family, food, memory and identity; and hidden histories and planetary futures.

The Jnanpith Award-winning writer spoke to Vineetha Mokkil about the urgent need to pay attention to history and ecology, stressing that “the world is full of wonder and you have to look out for the unknown.”

Plenty of supernatural elements feature in your novel Ghost-Eye. Beings from another world are an integral part of the spaces the characters occupy.

Yes, they are…This whole opposition between natural, supernatural, etc.—it’s a strange thing really. It begins in Europe during the Enlightenment period and is rooted in the conflicts between church and state. But it has no valence whatsoever within Asian traditions. Think of Japan. The Japanese are scientifically and technologically incredibly skilled. At the same time, they have a very powerful sense of the paranormal, of earth spirits, of ghosts. So, why should we in India import this kind of dualism into our world? It doesn’t make sense. It’s not rooted in our thought processes and beliefs.

In Bengal, folklore and ghost stories are woven into the fabric of people’s daily lives. Ghost-Eye seems to be deeply rooted in that tradition.

They are not considered supernatural, they’re natural. This reminds me of Rabindranath Tagore’s striking memoir of his childhood. He grew up in this grand house called Jorasanko and there was a tree on the property which was home to some kind of spirit. Everybody knew a petni (female spirit) lived in that tree and they treated it as normal. It was a perfectly natural part of their world. And that’s very much the world I also grew up in. Where there were all these other kinds of spirits and beings, and you knew that they existed.

Do you believe in God?

I would say I believe in gods…I wouldn’t scoff at organised religion, but it’s not something that I participate in.

Reincarnation and past life memories feature prominently in your novel.

There are so many documented cases of reincarnation across the world. A great deal of scientific research has been done on it. In fact, one of my closest friends in Bombay had past life memories at the age of three. He was walking by a house one day and he stopped his mother and said, “That was the house that I lived in.” There are innumerable cases. The evidence is so overwhelming that even Carl Sagan, the science communicator, said that this is one possibility you have to accept. But it is an uncomfortable thing to think about. Many people rooted in the here and now may find it disconcerting to open up to it.

‘Ghost-Eye’ is a metaphor for those who can see beyond what is commonly perceived as ‘real’. They are not discomfited by the uncanny.

If you think about it, the uncanny is fundamental to any kind of novelistic writing. Fiction is uncanny because it depends on uncanny techniques. For example, pre-figuring. Always in fiction, you have premonitions. A character feels something is coming. It just unfolds like that. The whole thing about writing is that a part of it is inexplicable. And in saying that, you’re also saying that it does come from somewhere else. From another source. There are times when I suddenly say to myself, do I actually have precognitive abilities?

Do you?

Not consciously. But when you write, I feel something comes in. In a sense, writers are the shamans of the modern world.

Calcutta of the 1960s is a big presence in your novel: the frequent power cuts, the almost constant state of rebellion, the strikes, protests, political churnings…

Calcutta has shaped me in profound ways. The Bengali language, Bengali literature—these are absolutely essential elements of my work. My own family was very conventionally Bengali. But I had many friends who had totally different kinds of lives. There were all these other cosmopolitan communities in the city: Anglo-Indians, Chinese, Armenians. We interacted with each other and so, all of us had some sort of familiarity with other cultures and lifestyles.

Calcutta has also changed a lot over the years. Still, there are distinct continuities. The neighbourhood I lived in used to be all little bungalows. But now, ours is probably the last bungalow left. When I was a child, there was a vast wasteland across the street from us where you could hear jackals howling at night. Now you can walk down the street and step into giant malls which sell designer garments. I mean, that’s just unreal!

Food (especially fish) is a key element of Ghost-Eye as it is in many of your other books. How would you describe your relationship with food?

I’ve always been interested in food at multiple levels. Cooking, eating. I love to cook. I improvise; throw in a bit of this and a bit of that until it tastes right. But I enjoy it very much. And I’ve also been the family cook forever. I always cook for my children. They didn’t value it much at the time, but now they do.

Food is the primary medium through which we relate to our environments and our cultures. And to each other. In that sense, we are now in a world where food systems are so disruptive that they have become almost unrecognisable.

Have you ever considered writing a cook book? Maybe something along the lines of Abhijit Banerjee’s Cooking to Save Your Life?

Abhijit is a very good friend. And a wonderful cook. But he’s an economist. So, he does things in systematic ways. I’m a writer, I’m not like that (laughs).

There is talk these days about ‘taking the farmer out of farming’. Many tech billionaires argue that food can easily be produced in labs…

That’s absolute madness. All that would do is to create extra fragility. There are so many levels of resilience in natural systems. Several forms of anti-fragility exist. People who don’t understand this are essentially nerds who spent their whole life staring at screens. They have no idea how the real world works, but they have all the power in the world at the moment.

In the digital age, we are cutting funding for humanities education, blindly chasing technological advancement.

The world is a much, much more mysterious place than we think. Take all these weird light phenomena that have been happening across the globe for millennia for instance…Without the humanities, we would become even more machine-like, more mechanistic. And as we can see, that sort of mechanistic mindset is what is taking us towards the destruction of the planet and the environment.

In Ghost-Eye, intervention of forces from other realms saves the planet from doom. Is that our only hope now?

The only hopeful trends that we see in relation to the environment today come from the rights of nature movement which recognises rivers, mountains, trees, glaciers as people. All of those small victories are founded upon the notion of the sacredness of the land. It’s a curious thing actually. Because the moment you accept that a river can be a person or a mountain is a living being with rights and an identity, what you’re really saying is that there are alternative worlds in which a river is a person or a tree is a person.