Summary of this article

Berlinale Jury president Wim Wenders came under fire for proposing that filmmakers ought to stay out of politics.

Festival director Tricia Tuttle said that artists are free to exercise their right of free speech in whatever way they choose.

Ahead of the 2025 edition, the Berlinale had clarified its position on freedom of expression, “welcoming different points of view".

On the opening day of this year’s edition, the Berlin Film Festival landed in a media soup. The first press conference with the main competition jury fielded the pivotal question by German journalist Tilo Jung about the Berlinale’s selective sympathies. Jung flagged that “the Berlinale as an institution has famously shown solidarity with people in Iran and Ukraine, but never with Palestine, even today”. Germany is one of the biggest exporters of weapons to Israel. Conveniently, the livestream was cut off before Jung’s question could be heard in its entirety. The festival claimed technical issues but the timing couldn’t be more suspicious.

Ewa Puszczynska, the Polish producer of the Oscar-winning Holocaust drama The Zone of Interest, termed the question unfair, adding that cinema cannot be held responsible for “the decision to support Israel, or the decision to support Palestine”. Jury president Wim Wenders came under fire for proposing that filmmakers ought to stay out of politics. He asserted that “movies can change the world”, but “not in a political way”.

The celebrated Paris, Texas filmmaker’s remarks sent shockwaves rippling, prompting Booker Prize-winning author Arundhati Roy to cancel her scheduled appearance at the festival. Roy, who was due to present her 1989 campus comedy In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones as part of the Classics section, wrote in a statement first shared with The Wire that she was “shocked and disgusted” by the “unconscionable” remarks of the jury. “To hear them say that art should not be political is jaw-dropping,” Roy wrote. “It is a way of shutting down a conversation about a crime against humanity even as it unfolds before us in real time–when artists, writers and filmmakers should be doing everything in their power to stop it.”

Wenders’ comments strike one as a reversal of his own well-quoted observations in his 1988 book, The Logic of Images:

“Every film is political. Most political of all are those that pretend not to be: ‘entertainment’ movies. They are the most political films there are because they dismiss the possibility of change. In every frame they tell you everything’s fine the way it is. They are a continual advertisement for things as they are”.

The controversy speaks to the timeless tussle with sociopolitical imperatives placed upon art, artists, spaces of curation. Wenders wasn’t alone in being dealt an immediate backlash. Oscar winner Michelle Yeoh and Neil Patrick Harris faced online criticism for their reactions to questions about politics and the rise of fascism, Harris for underlining that he was interested in “doing things that were apolitical”. When asked about the current state of the U.S., implying Trump’s ICE raids, Yeoh professed to having no understanding of U.S. politics, washing her hands of a position. English actor Rupert Grint was asked to share his feelings on fascism during a press conference for the Competition title, Nightborn. His hesitation (“I choose my moments when to speak”) was viewed as genuflection.

However, Hanna Bergholm, the Finnish filmmaker behind Nightborn, added that she believes it is “especially important that we don’t tell other fellow artists that they shouldn’t speak up when tens of thousands of people are getting killed. No one can say there is ever an excuse for that”. Her co-writer, Ilja Rautsi, also reiterated the need to create pressure so that awareness is drummed up, be it about Ukraine or the Gaza genocide. Other tacit rebuttals to Wenders’ remarks among the festival attendees quickly rose. Speaking to The National, Palestinian actress and filmmaker Hiam Abbas emphasised that “every act of daily life is political”, that there is a “lack of courage” in the film world. Art for art’s sake, the time for such pretence can no longer hold up.

In a statement, festival director Tricia Tuttle said: “Artists are free to exercise their right of free speech in whatever way they choose. Artists should not be expected to comment on all broader debates about a festival’s previous or current practices over which they have no control.” She called out the media ecosystem for folding every conversation into a news agenda. Insisting that “free speech is happening” at the festival, she redirected attention to the politics present in the films themselves. It might not always be about salvos targeting wider structures, governments, state policies, but also smaller acts of care to the invisible, the unseen, those at the periphery.

Films selected across the sections, though, are decisively locked into myriad political crises. Afghan director Shahrbanoo Sadat’s No Good Men, a satirical romcom about a camerawomen tackling life and work in Kabul, opened the festival. Mahnaz Mohammadi’s Panorama title Roya circles an imprisoned Iranian teacher forced into a dilemma between a televised confession and indefinite confinement. In the Generation section, Mehraneh Salimian’s documentary Memories of a Window examines the crackdown on student protests in Iran.

The Berlin Film Festival is no stranger to controversy and heated debate, especially linked to the Gaza question. While its slate of films struggles to find a life beyond the festival, intense media scrutiny has never wavered. It has always found itself in choppy waters, caught between denunciation and cowardice. For the past two editions, the Berlinale was lobbed with criticism over its stance on Gaza, its baulking at a clear condemnation, ostensibly tied to Germany’s backing of Israel. In 2024, a storm rocked the Berlinale on multiple counts. Organisers initially, as per protocol, invited Berlin parliamentary members of the far-right AfD to the opening ceremony. Instant uproar led organisers to withdraw the invitation.

Two directors of the parallel programme Forum Expanded withdrew their films, pledging support for the Strike Germany collective, which exhorts the boycott of all activities dependent on German state funds, like the Berlinale. At the award ceremony that year, while receiving the Best Documentary prize, Yuval Abraham, the Israeli co-director of the documentary No Other Land, which portrays the situation in the occupied West Bank, rallied for an end to “this apartheid, this inequality”, triggering death threats upon his return. There was also the brief hacking of the Berlinale’s Instagram page, flooded with pro-Palestinian posts. It didn’t take long for the festival to vehemently censure and reprove the unambiguous posts, hurrying to file criminal charges. Tame attempts at course-correction were put in place. The festival teamed up with social activists on a project called Tiny House, a mobile initiative for discussing the genocide in German schools and public spaces, a space for debate. A soundproof booth was installed in the premises. But these were inconsequential, too tiny steps. The Tiny House folded up within three days. Film critic Cici Peng wrote the project “reveals a dubious and distancing political stance”.

The Berlinale management team led by Carlo Chatrian resigned in the wake of an all-party campaign engineered by German Culture Minister Claudia Roth. Roth and the others slammed the festival jury as “antisemitic” for awarding a prize to No Other Land. When Tuttle, stepping in as the new festival director, maintained she didn’t believe either the film or its makers’ remarks at the ceremony were antisemitic, the pro-Israeli organisation “Values Initiative” charged at her.

The mayor of Berlin, Kai Wegner, reproached the winners and declared that Berlin is “firmly” on Israel’s side. The Berlin Senate declared it’d have its subsidies to the festival. In a 2024 interview with The Guardian, Tuttle shared her concerns that Germany’s stance on Gaza is putting artists off the festival. “People are worried about: ‘Does it mean I won’t be allowed to speak?’ Does it mean that I won’t be able to allowed to express empathy or sympathy for the victims in Gaza?”

Ahead of the 2025 edition, the Berlinale clarified its position on freedom of expression, “welcoming different points of view, even if this creates tension or controversy” while ensuring “a certain cultural sensitivity”. However, its website opposed the use of strong language in pro-Palestinian demonstrations which could be read as hate speech against Israel. It singled out the phrase “from the river to the sea”, highlighting its use could be prosecuted by law. Another row erupted after a pro-Palestinian speech given by Hong Kong director Jun Li at his film Queerpanorama’s premiere. Heckling from the audience followed as well as a police investigation into his speech’s import, where German institutions and the Berlinale were accused of complicity in the genocide.

The spectre of these numerous incidents carries over into this year’s edition. Neither is the Berlinale very different in its uncommitted attitude from other top fests, including Cannes. The latter might have sprouted in anti-authoritarian defiance, but its spirit as espoused by general delegate Thierry Frémaux seeks to prioritise cinema above “polemics”. The silence and passivity are crushing. In the run-up to last year’s Venice Film Festival, a large group of Italian film professionals under the banner of Venice4Palestine appealed for the festival to take a sharper pro-Palestinian stance and be unequivocal and braver. A characteristically mild, diplomatic response came from the parent organisation, the Venice Biennale, claiming it’s “always open to dialogue”. Such a mask of neutrality is classic moral dodginess, a failure of integrity that exposes its privileged silo in disturbing clarity.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Debanjan Dhar is a film fest-junkie & is fascinated by South Asian independent cinema.

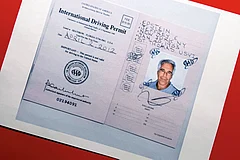

This article appeared in Outlook's March 01 issue titled Horror Island which focuses on how the rich and powerful are a law unto themselves and whether we the public are desensitised to the suffering of women. It asks the question whether we are really seeking justice or feeding a system that turns suffering into spectacle?