Summary of this article

Palestinian artists at the Kochi Biennale use installations to foreground memory, endurance, and political reflection, transforming remembrance into an act of resistance.

Works trace movement across geographies, linking Palestine and Kochi through histories of trade, migration, and colonial circulation, highlighting shared experiences of displacement and survival

Curator Nikhil Chopra emphasises sensory, embodied engagement, allowing art to invite reflection before judgment, returning the gaze to viewers

When you enter Aspinwall, the Kochi Biennale’s main venue, your eyes are drawn to a cluster of short, cobalt-blue structures on rods. At first glance, they resemble birdhouses crowned with turrets. Only on closer inspection do they reveal themselves as box-like forms punctured by keyholes — unsettling echoes of the watchtowers built across Palestine.

Elsewhere, at Pepper House, an outdoor sculpture is positioned precisely at 32° north, the latitude of Palestine. Then at 111 Markaz and Café, there are glass baubles with air from Palestine and Uttar Pradesh’s Firozabad. Together, these works — five in total across the Biennale — quietly insist on remembering Palestine. Amidst the bustling of new art, news fatigue and everyday life, remembering itself becomes an act of resistance.

The cobalt-blue structures of In Time Reclaiming Structures: Watchhouses by Palestinian artist and architect Dima Srouji and art curator Piero Tomassoni are scattered across an outdoor garden, crafted from mild steel and poised on slender stilts. At once spare and unsettling, the works respond to Israel’s weaponisation of architecture and archaeology as instruments of settler-colonial control.

“These are spaces of pause,” the artists write in an email exchange. Refusing constant stimulation, they create a rare stillness, one that carries both ecological and political weight. These are sites of protection, observation, and waiting; protection as they are forms of shelter, in a psychological sense; they encourage observation, inward as much as outward; and waiting in an attentive way rather than passive.

At Pepper House, a gleaming steel structure catches the light — and then redirects it. Yantra, the outdoor installation by New York-based Indian artist Utsa Hazarika, is inlaid with mirrored panels that reflect Kochi’s horizon, visually stitching together distant oceanic geographies.

The work draws on Delhi’s Jantar Mantar, the eighteenth-century astronomical observatory that later became a site of protest. Hazarika adapts the Samrat Yantra, a monumental sundial calibrated to its location’s latitude. Yantra (32°N/Horizon) follows this logic, aligning itself with the latitude of Palestine. “I use the poetics of scientific measurement to mark both place and politics,” Hazarika explains, referencing anti-imperialist traditions within the South Asian left and India’s long history of solidarity with Palestine.

A central periscope lets visitors view the horizon at ground level while standing above mirrored surfaces, evoking Kochi’s centuries-old role as a port and crossroads of the Global South. The horizon becomes a metaphor—for navigation, aspiration, and protest. As Biennale writer Arushi Vats observes, the installation “sutures” reflections, opening a view otherwise hidden from the courtyard.

Embedded within the Yantra’s history as part of a site that is known for protests and global solidarities, and the alignment of its form with Palestine, this suturing allows the viewer an unbounded view that would be otherwise inaccessible from the courtyard. First shown at New York’s Socrates Sculpture Park, the work in Kochi invites physical engagement: visitors can climb, sit, and walk through it, becoming active participants in its politics.

That research extends indoors. Inside the gallery, a large arc echoes the time-measuring scale of the Samrat Yantra and bears the names of political prisoners. Video works trace Adivasi resistance to mining and medieval European spiritual cartographies that shaped colonial mapping, with Palestine threading through these narratives, raising urgent questions about justice in a world that claims to be postcolonial, and yet remains anything but.

Kochi Biennale 2025 curator Nikhil Chopra positions Palestinian artists at the ethical and political heart of the Biennale. “The exhibition was conceived as a space for healing, reconciliation, and reflection, while attending to resistance and lives shaped by structural oppression,” he explains. He is careful to avoid tokenism, positioning Palestinian pieces alongside other works that speak to endurance and survival. In doing so, the exhibition resists reducing Palestine to suffering alone, foregrounding instead agency, presence, and complexity.

Central to Chopra’s thinking is the idea of remembrance. He describes many of the Palestinian works as acts of memory, where the body itself functions as an archive. “The body is also the archive,” he says, carrying histories not only through thought but through physical marks—through breath, aging, movement, and fatigue. Memory, in this formulation, is not static or purely mental; it is lived, accumulated, and transmitted across time.

This understanding of memory is closely tied to empowerment. Chopra is explicit in rejecting the aestheticisation of suffering, warning against exhibitions that turn oppression into something to be looked at, consumed, and then forgotten. What matters instead is how artists transform pain into material that allows them to reclaim agency. In this sense, Palestinian artists in the Biennale are not positioned as victims, but as subjects who speak back, who use the soft power of art to articulate political positions on their own terms.

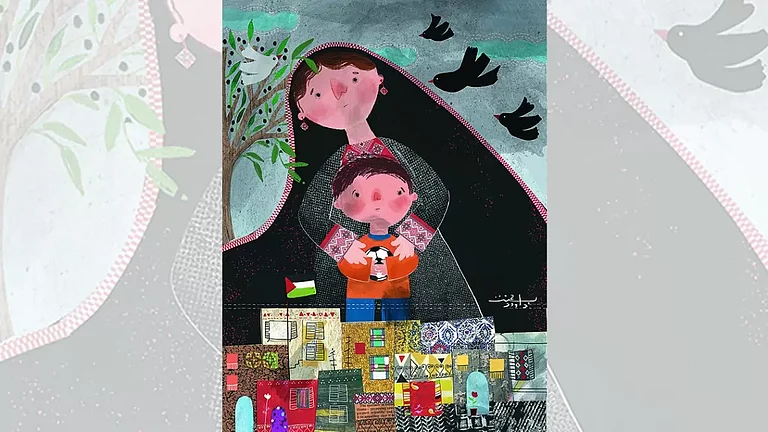

Ahmad Alaqra’s Seeding a Deformed Memory sculpture at the Devassy Jose and Sons site offers a vivid example of this approach. It traces the journey of the distaff thistle across maritime and overland routes linking Palestine, Arabia, and Kerala’s Malabar Coast. Resembling safflower, cultivated for dyes from Gaza to Kochi, the thistle likely travelled unintentionally with the textile trade. In Alaqra’s work, it becomes a quiet witness to precolonial exchange, where movement signifies continuity rather than exile. Its altered form, shaped through research and speculative reconstruction, reclaims the ecological and historical ties which once connected these regions.

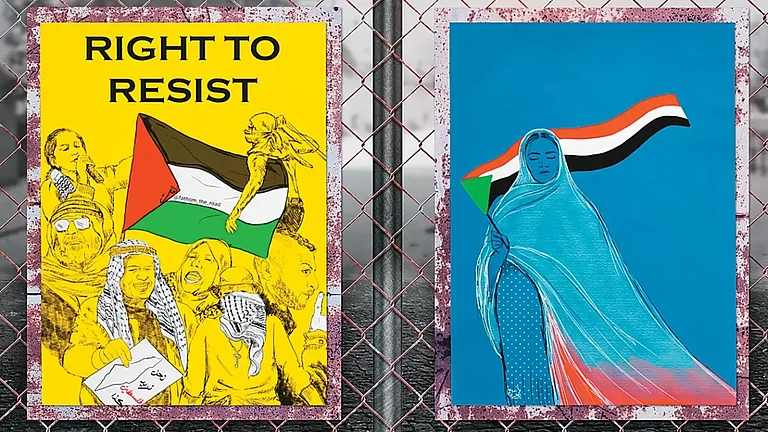

Building on this theme of circulation and continuity, the Dar Yusuf Collective’s exhibition So We Could Come Back traces migration as a fluid, cloud-like movement—gathering, dispersing, and returning in new forms. Through works by Emily Jacir, Ahmad Alaqra, and Andres and Francisca Khamis Giacoman, the circulation of bodies, kinship, and belonging across the Global South is reimagined. Their journeys—from Bethlehem to Rome, Santiago, Sharjah, and beyond—intersect like weather patterns shaping the same storm, portraying migration not as exile but as an ongoing movement of return.

Using photography, installation, and video, the artists show how Palestinian histories of movement resonate with other geographies of loss and belonging. In Kochi—a port city shaped by tides, winds, and centuries of exchange—the exhibition becomes a meeting of the Souths, a cloud of memories carried over water, where migration is transformation rather than departure.

Bringing Kochi and Palestine into dialogue highlights their shared histories of colonial circulation and extraction. Both are coastal crossroads where goods, materials, and people flowed across empires, and glass—traded along Indian Ocean routes—testifies to these entangled pasts. Seen together, these geographies resist framing suffering as isolated or exceptional, note Srouji and Tomassoni.

This connection is made tangible in Air of Firozabad / Air of Palestine (2025), Srouji and Tomassoni’s indoor installation at the Biennale. Hundreds of fragile glass baubles hover from the ceiling, barely visible, registering only through fleeting glints and shadows. One is handblown in Jaba’, Palestine; the rest are made in Firozabad, India—two centres of generational glassmaking. The suspended forms evoke breath under strain, turning the work into a quiet meditation on endurance, survival, and the ongoing struggle for land, heritage, and life itself.

For the artists, glass embodies contradiction. Formed under intense heat and pressure, it is both fragile and enduring. Its delicate nature mirrors precarity, while its capacity to be reshaped and repaired over generations speaks to resilience and survival.

Chopra observes that several works address the Palestinian body not literally but poetically. Hand-blown glass spheres infused with human breath—from Palestine and beyond—pose a deceptively simple, yet urgent question: whose air is it? By blurring the boundaries between breaths, the installation unsettles conventional ideas of borders, identity, and ownership. For Chopra, this asks not rhetorically but urgently “whose problem is Palestine?”, challenging viewers’ sense of distance and detachment.

By implicating the viewer’s own body in these works, Chopra argues, the exhibition refuses to frame Palestine as an external or abstract issue. Instead, it demands a reckoning with shared vulnerability and interdependence. Recent global events, he adds, have only sharpened this urgency. “We don’t live in a postcolonial world,” Chopra says. “We still live in a colonised world,” one that remains deeply fractured by racism, inequality, and the violent legacies of empire. Palestine, in this sense, becomes emblematic of conditions that are ongoing rather than historical.

Chopra emphasises that poetics must guide politics. Art, he contends, should first invite audiences through sensory experience and material presence, offering moments of pause before opening space for difficult conversations about Palestine and Israel. This approach resists spectacle, encouraging viewers to engage with feeling before forming judgment.

Central to the exhibition is how its interrogation of the gaze. Instead of reinforcing a colonial dynamic where viewers observe a distant, suffering “other”, the works return the gaze, implicating audiences in what they see. Art becomes a mirror, prompting recognition of one’s body, actions, and complicity in global systems of power.

Ultimately, Chopra insists that conversations around Palestine cannot be approached as someone else’s tragedy. An exhibition, he argues, should not instruct or moralise, but raise questions that linger, questions that may resurface long after the encounter, in everyday spaces and conversations. By engaging both bodily and emotionally, the works at the Kochi Biennale seek to create forms of memory that endure, transforming Palestine from a distant geopolitical issue into a shared, lived concern.