The Kolar Gold Fields (KGF) have long been declared a ghost town. Ever since the public sector Bharat Gold Mines Ltd (BGML) shut down operations in 2001, the whole area has worn a deserted look. That haunted aspect is getting more pronounced now with the mysterious and mass death of infants.

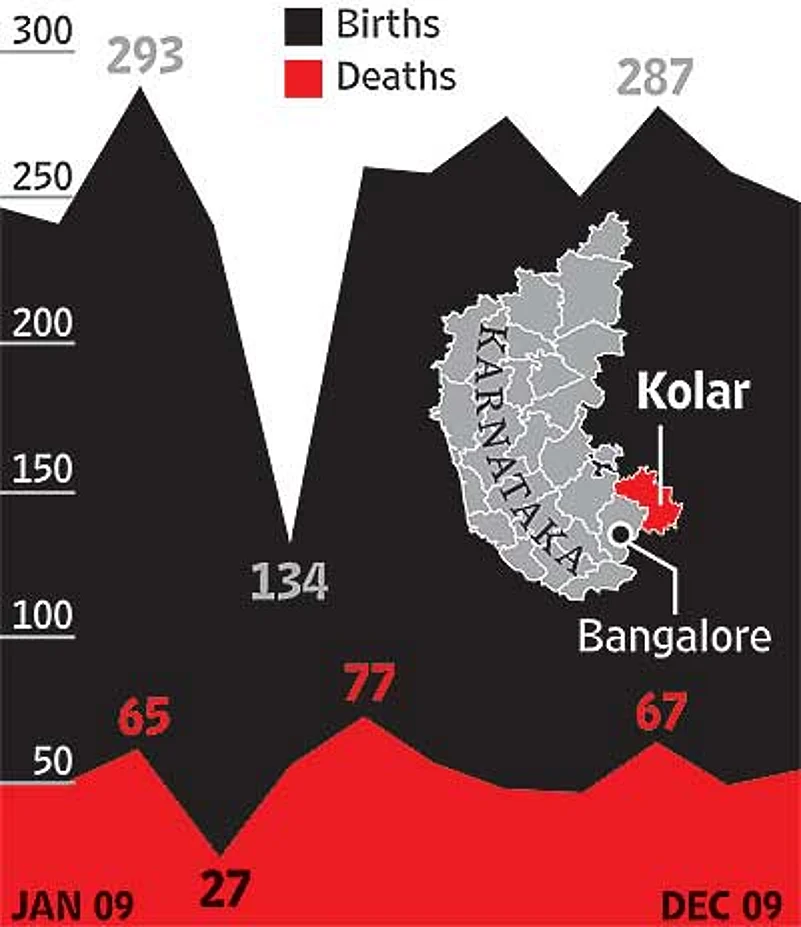

According to the birth and death statistics accessed from the local municipal office in Robertsonpet, in 2009 alone, out of the 3,042 children born in KGF, as many as 671 died. Most of them were below one year, and close to 90 per cent were born to Dalit women in the ‘coolie lines’ of the Marikuppam, Champion Reef, Oorigam and Coramandal mining areas. This alarming figure is actually four times the national infant mortality average, which at present is 52 per thousand live births.

The deaths have continued in 2010. The year began with 57 deaths in January, followed by 64 in Februrary while March clocked relatively less deaths at 42. Despite a public hearing organised in May by a local organisation, Samajika Parivarthana Janandolana, which was attended by the chairpersons of the State Human Rights Commission and Child Rights Commission, the people of KGF have not been able to attract the attention of the authorities. They do not even know what really is causing these unprecedented deaths. No scientific study has been commissioned to nail the truth, and what is being circulated is an assortment of conjectures.

When Outlook contacted a few mothers who had lost their children in 2009, most of them refused to speak. Those who did, spoke with trepidation. Strangely, they wouldn’t give out the names of the children they lost. In the case of 26-year-old Jamuna, who lost her baby in August 2009, her mother Vasagi attributed the death of the child to “high fever”. “We took the child to the local hospital in Robertsonpet,” she tells us, “but the doctors directed us to a hospital in Kuppam across the border in Andhra. In the middle of the night, we had to beg for Rs 750 to arrange an ambulance, but as soon as we reached the hospital, the child died.”

Vasagi, who lives in the ST Block of Champion Reef, would not allow us to see Jamuna, as she had delivered another baby a few days back and they now had to protect it from the “evil eye”. Jamuna’s husband is a carpenter and travels to Bangalore each day looking for work. After the mines closed down, most men take an early morning train to the city, 70 km away, in search of work. There are an estimated two lakh people living in the BGML mining area.

Their case echoes many others. Nandakumari, 26, lost her baby the moment it was born in March 2009. Sudha, 35, lost her child in the same month. Her baby was delivered at home, but it was immediately taken to a maternity hospital outside the mining area for post-natal care. Still, it died within two hours of reaching the hospital. Sudha, who lives in the Smith Block of Champion Reef, has three other children, who, she says, “luckily” are doing fine.

Among all the women we spoke to, 37-year-old Savitri was the most forthcoming. She and her husband Vijaykumar live in the Weslyan Block of Coramandal and said they lost their three-year-old son in February 2009. The reason apparently was kidney failure. “We borrowed close to one lakh rupees for his treatment, but he did not survive. After he died, we burnt all his medical records,” says Savitri.

Sea Of Death

Organisations such as Aadima Shakti and the KGF People’s Movement, which have been working for many years in KGF, speculate that the principal reason behind these child deaths could be the water that people in the mining areas consume along with the absence of basic sanitation. Naryanaswamy of Aadima Shakti says, “They buy water from tankers, whose source are borewells. These borewells draw water collected in mining shafts and tunnels beneath the ground created over hundred years. There is also a possibility that the stagnant water in the underground tunnels has polluted the groundwater in the area. Earlier, when mining activity was on, water used to be pumped out of these tunnels regularly, but now nothing of the sort happens.”

Lawyer P. Susai Raj Babu of the KGF People’s Movement adds: “As early as 1890, one British doctor, O’Daniel, had given a report that water in the mining area was unsafe. That was the reason for them to draw water from the Bethamangala tank, far away from the mining area. But the supply of water from the tank was stopped immediately after BGML was shut down. Now the only source of water for these people are the tankers. They pay Rs 1.25 a pot.”

Besides water and sanitation, the humungous ‘cyanide dumps’, a vestige of the mining years, with a height of nearly 30 metres from the ground at many places, are also a cause of major health concern as the coarse dust flies across the township. KGF has anyway been a hotbed of Silicosis for decades. Worse still, the most sophisticated and century-old BGML Hospital in the mining area also shut down with the ending of mining activity in 2001.

The local BJP mla, Y. Sampangi, and the district health officer were not available for comment. The political disadvantage that people in the mining area face is that they are Tamils, having migrated from Tamil Nadu as indentured labourers more than a 100 years ago. Until 2008, they elected an aiadmk member as an mla. KGF, although technically in Karnataka, borders both Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. This makes them ‘outsiders’ for the Kannada population in the non-mining areas of Kolar as well as across the state.