Ram’s image has shifted from spiritual figure to political symbol in modern India.

The Ayodhya movement redefined devotion as a marker of identity and power.

Competing interpretations of Ram reflect deeper social and ideological divides.

Ram is everywhere. In names, places, songs. In grain fields and hilltops. He is in the chants of Ayodhya, in the poets of Chhattisgarh, in the footpaths of Kashmir. However, this idea of Ram shifts when the RSS enters that terrain: Ram becomes more than a myth, taking on new meaning as a marker, a claim, and an era.

For the RSS, Ram is not just the Lord of the Ramayana. He represents what they call the “self” (swa) of Bharat. In January 2024, the Ram Temple in Ayodhya was consecrated as the “Pran Pratishtha” of Ram Lalla. The RSS chief called that day India’s moment of “true independence.”

Earlier, the celebration of political independence in 1947 marked a victory over colonial rule. This new declaration instead frames the Ayodhya event as a spiritual, cultural, and civilizational restoration long delayed.

The consecration ceremony carried many symbolic loads: revival, reclaiming, and homecoming. Prime Minister Modi presided over the rituals, with Mohan Bhagwat by his side. For the RSS, it was more than religious fulfilment. It marked a fulfilled promise: a visible anchor for narratives of belonging.

Yet, as with all major symbols, Ram becomes a contested one. This was clear when Bhagwat’s comment about “true independence” drew sharp criticism—from opposition parties who stressed the primacy of 1947’s freedom, and from those warning against politicising faith. The debate revealed how deeply entwined myth, memory, and power have become.

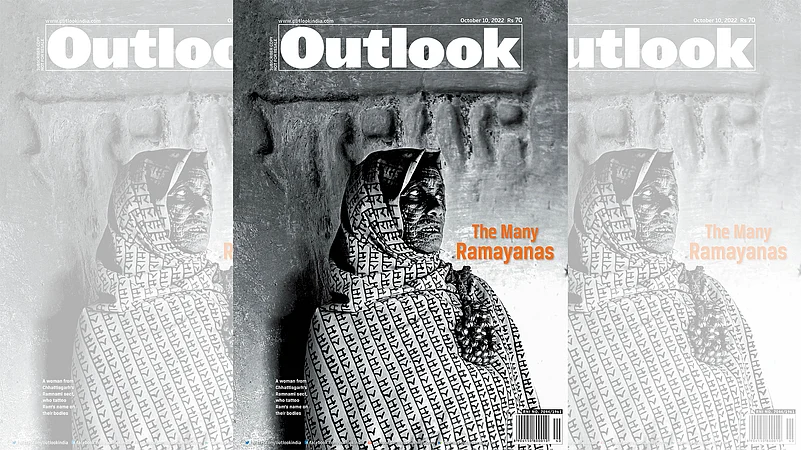

In that glow and friction, Ram reveals his infinite, unknowable face. He is the primordial hero, the idol enshrined in gold and gems, and the symbol whose battleground is the nation's future. For devotees, dissenters, pilgrims, and narrators, Ram is a quest—a quest for unity, identity, transcendence. And somewhere in that quest lies the question: when myth becomes state, who writes the story? Outlook’s October 10, 2022 issue The Many Ramayanas, explores this question.

In the cover story, The Many Faces And Transformations Of Ram And His Story, Ashutosh Bhardwaj looks into how the Ayodhya movement lent Ram a political identity.

The BJP’s narrative on Ayodhya is also a retelling, which, like any major retelling of the previous eras, has transformed the reception of the deity and psychology of his devotees. If Tulsidas made Ram a self-effacing family man and king to be worshipped and idolised in millions of households, the Ayodhya movement lent him a political identity. Tulsidas’s Ram was a stoic and gentle being. L.K. Advani’s Ram is an electoral warrior, writes Bhardwaj.

In Ram Van Gaman: Where Ramayana Is Not Just A Story, But Is Actually Alive, Amish Tripathi, bestselling author, recalls travels through Chitrakoot, shooting for a TV show on the Ram Van Gaman trail.

In Ram as Purabiya's own family man, Nirala Bidesia highlights that in the traditional folk world of the region, Ram is popular as bridegroom and Ram as groom or son-in-law takes precedence over Ram the victor.

In 'Sri Ram To Me Is Not Just A Deity, But A Way Of Life', Outlook asked people across India who Ram is and what the Ramayana means to them.

Snigendhu Bhattacharya explored the flip side of the politicisation of the Hindu god in relation to the issue. In Rebels’ Ramayana: Periyar And Ambedkar’s Critique Of Ramayana, Bhattacharya writes that Ambedkar and Periyar’s “radical interpretations of the Ramayana, India’s oldest epic, came much before Ram was to become a political icon in free India. But the two targeted these epics, particularly Ramayana, after coming to the understanding that these stories help perpetuate subjugations—of the Dalit by the Brahmin and the upper caste, and of the non-Aryan by the Aryan. Both of them had fallen out with the Congress before Independence, once they realised the party was controlled by the upper castes.”