Summary of this article

After seven years in custody, Mahesh Raut was granted interim bail amid ongoing delays in the Bhima Koregaon case.

The case evolved from 2018 caste violence to allegations of a wider Naxal conspiracy involving activists.

With the trial still pending and over 300 witnesses yet to testify, the death of Stan Swamy in custody underscores serious systemic issues.

The Supreme Court on Tuesday granted interim bail to Elgar Parishad-Bhima Koregaon case accused Mahesh Raut on medical grounds. Raut’s counsel, senior advocate C U Singh, submitted that the accused was suffering from rheumatoid arthritis and required special medical care unavailable in prison or at JJ Hospital, where he has been examined.

A bench of Justices M M Sundresh and Satish Chandra Sharma stated that “The applicant is seeking interim bail on medical grounds coupled with the fact that he was actually granted bail (by Bombay High Court), we are inclined to grant medical bail for a period of six weeks."

The Bhima Koregaon-Elgar Parishad case began after caste violence broke out during a Dalit gathering in 2018 near Pune.

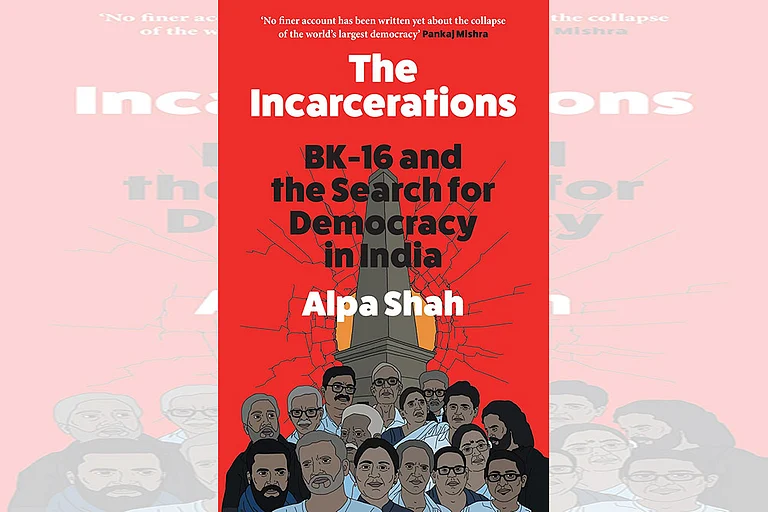

Outlook reported how the Bhima Koregaon Case transitioned from Caste Violence into allegations of it being a Naxal Conspiracy. In early 2025, the Bombay High Court granted bail to prominent rights activists Rona Wilson and Sudhir Dhawale in the 2018 Bhima Koregaon-Elgar Parishad case.

As of 2025, the trial is yet to begin with over 300 witnesses to testify in the case.

Shweta Desai explained how the Pune police claimed to have found incriminating evidence in Wilson's laptop from suspected Maoists on a plot to assassinate Prime Minister Narendra Modi. A US-based digital forensics firm, Arsenal Consulting, found that Wilson’s laptop was hacked by members of the Pune police and infiltrated by malware.

According to the security agencies, the accused were part of a larger conspiracy to overthrow the government and were involved in procuring arms, recruiting, and funding Naxal activities.

What had happened?

On January 1, the morning of the new year in 2018, violent clashes broke out in the Koregaon Bhima village near Pune. The incident occurred as thousands of Dalit people gathered at the Vijay Stambh- victory pillar to mark the bicentenary celebrations of the Bhima Koregaon battle. Mahars, the formerly untouchable castes fought the historic battle in 1818 on the side of the British forces and defeated the Peshwa troops, thereby officially ending the Maratha confederacy and expansion of British rule in Maharashtra.

The Elgar Parishad conclave was held in December 2017 at Shaniwarwada, Pune. Investigators alleged that provocative speeches delivered at the event instigated the violence at Koregaon-Bhima on January 1, 2018.

The direct conflict between Hindutva and the Ambedkarites’ views have turned Bhima-Koregaon into what it is now: A Battle Over Past and Present.

Snigdhendu Bhattacharya highlighted how on January 2, 2018, a day after communal clashes in Maharashtra’s Bhima-Koregaon claimed one life, left several injured, and caused property destruction, a Dalit political activist took action. Anita Sawale lodged a police complaint naming Hindutva organisers Sambhaji Bhide and Milind Ekbote for leading a Hindutva mob and inciting them to attack a gathering of anti-caste activists.

Bhide, who has also been seen in the same frame with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, was never arrested. Ekbote was arrested in March 2018, after the Supreme Court criticised the police for failing to arrest him. He, nevertheless, obtained bail the next month.

In contrast, another police complaint lodged on January 8 by Tushar Damgude, who was known to be a close associate of Bhide, alleging the involvement of the members of the banned CPI (Maoist) behind the anti-caste gathering. This became the main tool in the hands of the police in conducting the investigation.

They arrested not only the activists named in the complaint but also eminent civil society personalities who were not named. They were arrested under various sections of the Indian Penal Code as well as the provisions of the stringent anti-terror law, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act.

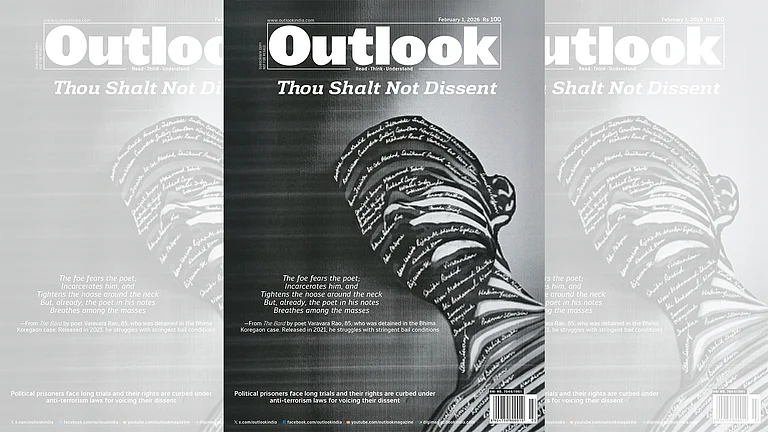

Eventually, the Pune police came up with the claim that these civil society activists, including poet Varavara Rao, lawyer Sudha Bharadwaj, journalist Gautam Navlakha, scholar Anand Teltumbde, Jesuit ‘Father’ Stan Swamy, professors Shoma Sen and Hany Babu, were involved in a plot to assassinate Prime Minister Narendra Modi. When the BJP government in Maharashtra fell, the National Investigation Agency (NIA) under the Union government promptly took over the case.

One of the accused in the case, 84-year-old tribal activist Stan Swamy died on July 5, 2021 while he was in custody. The question immediately arose, Who Killed Stan Swamy?

Ruben Banerjee states that Swamy’s passing could be explained in many ways. He was old and ailing. But the circumstances under which he ultimately died makes it even more sad. Arrested in 2020 in connection with the Elgar Parishad case, which many consider to be nothing more than a witch hunt by the Maharashtra police at first and subsequently by the NIA, Swamy was in the custody of the state when his end came. And the state, together with our judiciary whose doors the infirm Swamy repeatedly knocked for help, let him down very badly.

The final days and months of Swamy remain as a stark reminder to the many things that are so horribly wrong with our system.

Picked up and whisked away by the NIA from his Ranchi residence on October 8, 2020, his friends said he was treated very rough at the time of his arrest. Swamy, despite his advanced age and failing health, found himself in jail. He repeatedly petitioned for help, small mercies in fact, but repeatedly came up against a wall. His health deteriorated further during his incarceration and he struggled to get even such things like a sipper that could have allowed him to drink with relative ease. His pleas grew desperate with time and he moved the courts again and again. Only recently, he again petitioned that he was finding it increasingly difficult to carry out his normal chores. But steeped in red tape, the courts were slow to respond.