BJP leaders, including Amit Malviya, defended calling Bengali a “Bangladeshi language” in the context of identifying infiltrators.

There is no officially recognized language called “Bangladeshi.” Bengali is spoken on both sides of the border and globally known as one unified language.

Dialectal diversity exists within West Bengal too, often more than between Bengal and Bangladesh. Yet all fall within the same grammatical and phonetic family.

In their bid to separate the Bengali spoken in India from that in Bangladesh, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), India’s ruling force, has formally invented a new language called Bangladeshi.

Bengali, or Bangla in the native pronunciation, is India’s second-most spoken language and one of the country’s 22 Scheduled languages included in the Constitution. With about 10 crore native speakers in India and another 16 crore in Bangladesh, it is also South Asia’s second-most-spoken and ranks seventh in the world. It is known as Bengali in all areas of native speakers and globally as well.

However, after the Delhi police first referred to Bengali in a July 29 letter as a ‘Bangladeshi language’, BJP leaders jumped into their defence.

“Delhi Police is absolutely right in referring to the language as Bangladeshi in the context of identifying infiltrators (from Bangladesh),” BJP spokesperson Amit Malviya said in a social media post on August 4 while pointing out how different dialects of Bengali widely vary.

He argues that the official language of Bangladesh is not only phonologically different, but “also includes dialects like Sylheti that are nearly incomprehensible to Indian Bengalis.”

In a more staggering claim, Malviya said, “There is, in fact, no language called ‘Bengali’ that neatly covers all these variants.”

He went one step ahead in defining the Bengali people: “‘Bengali’ denotes ethnicity, not linguistic uniformity.”

Malviya’s remarks are at least ill-informed, if not ill-intended.

The Delhi police referred to the written language, i.e. the Bengali script, as Bangladeshi. This is why the question of dialect does not arise. Identity documents, which contain proper nouns, are no different in the Bengali written anywhere.

Second, he either has no idea, or prefers to skip it, that the Bengali used in southwestern West Bengal’s Purulia-Jhargram region and that of northern West Bengal’s Jalpaiguri-Cooch Behar region is more mutually incomprehensible than the dialects of West Bengal’s Nadia and Bangladesh’s Kushtia.

Suniti Kumar Chatterjee asserts in his 1926 book, the Origin and Development of the Bengali Language, that there exists as pan-Bengali language.

“The Bengali dialects cannot be referred to a single Primitive Bengali Speech, but they are derived from various local forms of late Magadhi Apabhransa, which developed some common characteristics that may be called pan-Bengali,” he says.

Chatterjee, one of India’s foremost linguists of his time, argues that these pan-Bengali features link the dialects together as members of a single group, and enable them to lie attached to a composite literary language.

“The literary language has all the pan-Bengali characteristics, but sometimes it leans to one dialect and sometimes to another, although its basis is ‘Gaudiya’ or Typical West Central Bengali,” Chatterjee writes.

Spreading Misconception

Malviya dons many hats as the in-charge of BJP’s national Information & Technology department, co-incharge of West Bengal state and a member of the party’s national executive. His remarks carry weight.

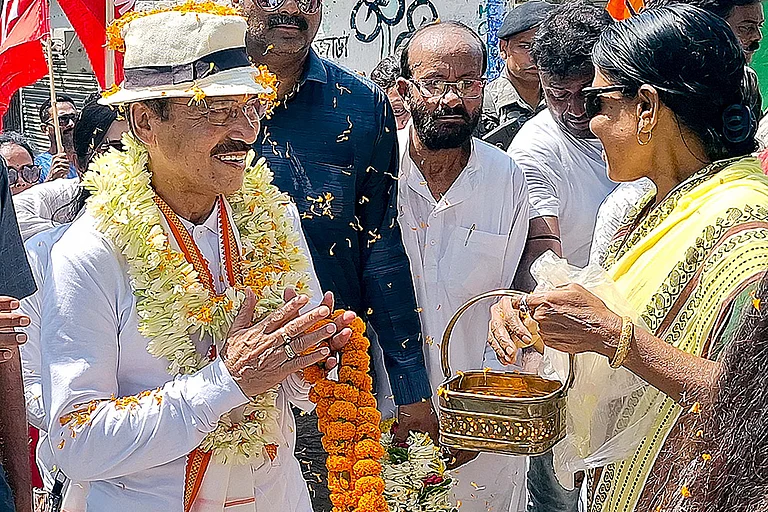

Coming at a time several thousand Bengali-speaking natives of West Bengal have suffered random and arbitrary detention in different BJP-ruled states as suspected Bangladeshis since the end of April—to the effect of some bona fide Indian citizens being deported to Bangladesh—such remarks endanger the safety and security of every Bengali-speaking Indian.

But Malviya is not alone. The BJP’s Bengal unit president, Rajya Sabha member Shamik Bhattacharya, too, asserted that the Delhi police had used “the correct word.”

Bhattacharya argues that the language used in Bangladesh is clearly distinguishable from that used in West Bengal. The language of Bengali text from a Hindu writer in West Bengal and another from a Muslim writer in Bangladesh will be different, he says.

What he most likely means is that the Bengali prevalent in Bangladesh is replete with Arabic and Persian words.

“It cannot be granted that anyone speaking in Bengali is an Indian and should have their names in India’s voter list,” the Bengali media quotes Bhattacharya as saying.

The fact is, there has been no such language as Bangladeshi language and it’s an entirely new nomenclature that the BJP can claim copyright for.

From Chattogram in eastern Bangladesh to Purulia in southwestern West Bengal, from Assam’s Kachhar region, Tripura and Meghalaya in the northeast India and Jalpaiguri-Cooch Behar in northern West Bengal to the Sundarbans in southern West Bengal—dialects are many but the language is the same.

The Bengali spoken in Assam and Tripura are far closer to the Bengali in Bangladesh than in West Bengal. Bengalis from Assam’s Kachhar and West Bengal’s Bankura would find much of the speech incomprehensible if they speak, or write, in their local dialects.

The Bengali spoken in parts of northern Bengal is often closer to Assamese, and that spoken in central Bengal has Maithili influence, whereas the language spoken is southwestern West Bengal contains influences of Odia, Santali and Kurmali.

Chatterjee divides Bengali dialects into four major groups—Rarha, Pundra/ Barendra, Banga and Sumha. He notes that the extreme Eastern forms of the Banga speech, in Kachhar of Assam, Tripura and Sylhet, Noakhali and Chittagong of Bangladesh have developed some phonetic and morphological characteristics which are foreign to the other groups.

While Malviya argues that the diversity of dialects shows how “‘Bengali’ denotes ethnicity, not linguistic uniformity,” Chatterjee shows us the exact opposite.

Chatterjee attributes the difference in dialects to different ethnic roots of a people who have been bound by a language.

Chatterjee says that the differences in pronunciation and stress, as well as in general enunciation and grammar, which are observable in the Bengali of a Manbhum (Purulia) peasant in southwestern West Bengal, and in that of one from Mymensingh in northeastern East Bengal, “are certainly connected with the fact” that the former is mainly Kol (or mixed Kol and Dravidian), and the latter a modified Bodo (Tibeto-Burman), by origin.

Inalienable Islamic Contribution

In essays written during the 1870s and the 1880s, contained in the book, Bibidha Prabhanda (vol. 2), Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, the composer of Vande Mataram (Bande Mataram in Bengali text and pronunciation), said that the Bengali people include four key groups—the Aryans, the non-Aryan Hindus, an Aryan-non-Aryan mix and Muslims.

Chattopadhyay held that the modern Bengali language is born out of a mix of Sanskrit, non-Aryan languages, Arabic and Persian.

Yes, however much Hindutva may dislike the fact, Arabic and Persian have been part and parcel of the Bengali language for at least seven centuries. Muslim conquerors who settled here from abroad contributed not only words but many of Bengal’s Muslim rulers were actually major patrons of Bengali literature.

In the 1911 book, History of Bengali Language and Literature, Dinesh Chandra Sen shows that Bengali language developed mostly during the non-Hindu rule.

Sen says that written Bengali first developed during the Buddhist Pal dynasty’s rule. Thereafter, the Hindu rule hindered the growth of Bengali literature, as the Sen dynasty mostly patronised Sanskrit scholars.

“With the decadence of the power of the Buddhist priests, Bengali lost the patronage which it had secured of the lettered men of the country,” he writes, adding that the form of Prakrita prevalent in Bengal was in disfavour with the Sanskritic school which gave it a contemptuous epithet.

Bengali seemed to have no prospects with such Sanskrit scholars who “zealously opposed” efforts of writing in Bengali.

To prove his point, Sen also quotes a well-known Sanskrit couplet that “bears testimony to their ill-will” against Bengali. The couplet, in Sen’s translation, says that if a person hears the stories of the eighteen Puranas or of the Ramayana recited in Bengali, he will be thrown into the hell called the Rourava.

Sen shows that the Bengali language started flourishing with the beginning of the Turk (popularly called Pathan rule in Bengal) rule in the 13th century. He opines that had the Hindu Kings “continued to enjoy independence, Bengali would scarcely have got an opportunity to find its way to the courts of Kings.”

Sen asserts it was following the example of Muslim rulers that Hindu kings started appointing Bengali poets to their courts. “The patronage and favour of the Mahammadan Emperors and chiefs gave the first start towards recognition of Bengali in the courts of the Hindu Rajas,” says Sen’s book.

He gives the example of Paragal Khan, the fifteenth century governor of Chittagong—the eastern border of the Bengali homeland—who used to listen to Bengali translations of Mahabharata in his court full of illustrious audience. The translator, who was a Hindu, called Paragal Khan a reincarnation of Lord Hari in a show of flattery. The Pathan chief, despite being a devout Muslim, did not take it as an offense.

American historian Richard Eaton’s 1993 book, The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760, paints a similar picture. The rule of the Hossain Shahi dynasty saw Sanskrit and Persian being cornered and Bengali coming to the forefront, Eaton writes. The kings wholeheartedly backed Bengali and immersed themselves in the local traditions, including adopting Hindu rituals.

Chatterjee notes that towards the end of the 18th century, the Bengali speech of the upper classes, even among Hindus, was highly Persianised. He adds that some 2,500 Persian words were added to the Bengali vocabulary “in Bengalised forms” and used by most sections of the people, together with a few Persian affixes which had become “thoroughly naturalised.”

He foresees increasing use of Perso-Arabie words, especially relating to the Mohammedan religion and to Islamic culture, into the language. But he found it natural, as “an ever-increasing number of Musalman writers of Bengali are coming to the front.”

While the usage of Persian and Arabic words have increased in Bengali in eastern Bengal since Chatterjee published the book a century ago, words of so-called ‘Hindu’ or Indian origin having or post-Sanskriti roots are still the dominant ones there.

In the 1927 book, The History Of The Bengali Language, Bijaychandra Mazumdar points out that “no amount of word-borrowing can change one language into another.” He highlights that the words borrowed from other languages have all to conform to the genius of the languages into which they are adopted.

“The vulgar people confound language not only with vocabulary but also with script,” Mazumdar writes, adding, “If we borrow European words more freely and adopt what is called Roman script in our writing, will the Bengali language be entitled to claim another name?”