Leaning against the mud-caked bamboo wall of her house, Dipa Telenga looks out towards the rows of neatly trimmed tea bushes in the distance. She holds a framed photograph in the crook of her arm—a photo of her parents who died in one of Assam’s worst hooch tragedies on February 24. Dipa is just 16 but has aged since the tragedy; she is now also the mother-figure for her brother Sachin, 11. She stays with her relatives in Halmira Tea Estate in Golaghat district, trying to find the meaning of life and death in a community historically oppressed and exploited for centuries.

But it’s not only Dipa or Sachin’s story. At least 45 children, aged between a few months to 16 years, were orphaned when 158 people, all of them tea garden workers, died after consuming spurious liquor in several tea gardens in Golaghat and adjacent Jorhat district. An Adivasi student leader says the death toll would be more than 200 as many deaths were not officially recorded by family members. Most of the orphans have been taken away by their relatives or put up in different orphanages and child care homes, including Dipa’s brother. At least 94 people died in Halmira, the worst hit.

“I don’t know what to say...life has been very cruel to us. I just want a better life, for me, my brother and our entire community,” says Dipa, a Class VI student in a government school. She started her education quite late like many children in the impoverished community. Dipa and her aunt are also worried about Sachin. “We have heard that they are not doing well at the orphanage (in Bokakhat town). We don’t know if they are given proper food or not. So, we want to keep him with us,” says Rani Telenga, Dipa’s aunt and a mother of two.

It’s hard to miss the irony when Huntu Turi, 15, of Borhola Tea Estate in Jorhat district, says he was “lucky” to have escaped becoming an orphan. He lost his mother and uncle and his father would have been among the dead if not for some “urgent work”; he didn’t drink that day. “That day was terrible…it was scary…I saw so many people crying in our neighbourhood and in the hospital as well…it was terrible,” says Huntu, choking on the words as he is overcome by grief. He stopped going to school but says he has resumed his classes. Huntu is the eldest of three children of Ajit Turi.

“I was engaged in some other work and so I didn’t drink that day. When I reached home, my wife and her brother complained of feeling uneasy. They vomited in the morning and their condition deteriorated fast. By the time we reached Jorhat Medical College, they were dead,” he recalls.

For the tea garden workers, drinking the local brew known as ‘sulai’ is the only way of escaping the drudgery of their struggle with life. Most of these workers—who live in squalid row houses in designated areas known as the ‘labour lines’—barely earn Rs 165 per day, barring Sundays and holidays. Their monthly income comes to just about Rs 4,000. When both the husband and wife work, it’s double. But most of the income goes in drinking, a habit encouraged by the British who brought thousands of these hard-working people from Jharkhand, Odisha and Bihar to clear forests for setting up tea plantations.

Police say that the bootleggers probably used methyl alcohol instead of ethyl alcohol (used in making liquor) which turned out to be the “killer” on that cold February day. Though there are government-authorised breweries which make rice-based drinks, the garden workers prefer the cheaper ‘sulai’. It is also the preferred drink because its effects kick in earlier.

Mol Mriddha, 40—who lost her husband and brother-in-law—says her daughter is the only hope now. Her daughter Bobita studies in a college and stays away but Mol doesn’t want her come back. She also has two younger sons and now has to look after the two children of her brother-in-law, whose wife left him earlier. “Now, we are six. The kids of my brother-in-law are very young, just six and seven...It’s my responsibility to look after them. I don’t know how to run the family now with my meagre earnings,” Mol tells Outlook at her residence in Borhola Tea Estate. “It’s a curse to be here,” she adds.

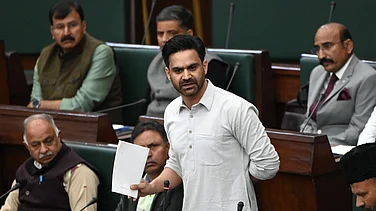

Many say that the government must ban liquor completely to avoid such tragedies. Benedict Toppo, a local leader of the All Adivasi Students’ Association (AASA), says they have been demanding improvement in the pay and living conditions of the workers for a long time. “Assam is one of the best producers of tea in the country but see the condition of the workers. It’s the worst. Tea garden workers in West Bengal, Kerala and Odisha are far better than us in Assam. We have been demanding that the wage should be hiked at Rs 351 per day. But that too is not happening,” Toppo tells Outlook. Assam excise minister Parimal Suklabaidya says the government is working on ways to curb the production and sale of illicit liquor, including increasing the quantum of punishment for culprits. “We are planning at least five years of imprisonment and fine up to Rs 10 lakh,” he declares.

At Borholla, a few children play in an open field as people work on erecting a temporary dais. It’s election time and a candidate is scheduled to address the workers for their votes. “It’s always about our votes. Then no one remembers us,” says Dipa, who has not even attained the voting age. But she knows by now. Life is a big lesson. Death even bigger.

By Abdul Gani in Golaghat