Summary of this article

Kumbalangi Nights is a Malayalam film, directed by Madhu C. Narayanan and written by Syam Pushkaran.

The film stars Fahadh Faasil, Soubin Shahir, Shane Nigam, Sreenath Bhasi, Anna Ben etc.

The film completes seven years today and this evocative article brushes through its emotional surface, exploring its quiet intimacy and nuanced portrait of masculinity.

Madhu C. Narayanan’s luminous portrait of four brothers living at the edges of Kochi significantly reshaped what inheritance could mean—in terms of masculinity, desire and even the architecture of a family. Narayanan’s film released in 2019 and turns seven today. In that span, the world has moved through a pandemic, fracture and reinvention; yet, it keeps sliding into new forms of unrest. In such a landscape, the film still holds faith in carrying scattered fragments of home, locating companionship and claiming small everyday pleasures.

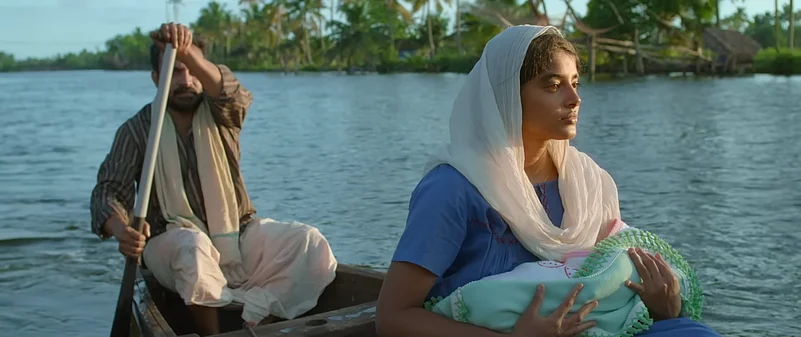

By no means does the film aim to search for a remedy to loss. It proposes something else: an ethic of assembled belonging. A broken house, like the one the film inhabits, never comes with spare parts. It has to be rebuilt through attention—one careful act at a time, one person leaning into another. Those moments gather into a chosen family, one shaped by intentional love rather than blood alone. And so, Kumbalangi Nights stands as a family portrait earned through struggle that insists on existing with full, hard-won conviction. The film lingers long after one has witnessed it. Its quiet canals, emerald stretches and lived-in community create a striking terrain to examine masculinity unvarnished.

The Shape Of A Missing Father

The missing father figure works as a central hinge in the narrative, pushing the men forward as a force of motion rather than a single-point cause. Parental absence, whether maternal or paternal, moves with a distinct pulse, shaping their conduct, decisions and sense of self—much as it does beyond the screen in everyday experience. One home carries only men while the other has three women and a man. Both spaces malfunction, shaped by panic, social scrutiny and emotional rupture.

Saji (Soubin Shahir) stands as the eldest and the emotionally fractured core, carrying residues of guilt, fear and inherited shame. He admits he cannot cry and that it hurts when people call them “fatherless.” Through Bobby’s narration of their unconventional family, the deep connection between Saji and Bonny becomes clear. When Bonny finally strikes out at Saji, it shatters his fragile internal balance leading him to self-harm. As Saji repairs himself piece by piece, the house responds in parallel, regaining order in quiet, personal ways. Bobby (Shane Nigam) and Franky (Mathhew Thomas) also mourn a mother who is alive yet distant, trapped within social expectations she cannot escape.

Shammi (Fahadh Faasil) enters as a fabricated patriarch, who sees himself as the model of manhood while burying private anxieties beneath dominance. His presence reveals a parental pattern where intimidation becomes governance. Much like Balbir Singh (Anil Kapoor) in Animal (2023), masculinity becomes an ever-lasting hyper-curated performance aimed at meeting an impossible script: emotional indifference, aggression, control through fear and ownership of women. Men like him end up shaping children who keep chasing masculine validation, the way Ranvijay (Ranbir Kapoor) does. In other cases, a figure like Kamal Mehra in Dil Dhadakne Do (2015), also played by Anil Kapoor, models children who grow up managed rather than nurtured, carrying quiet resentment toward the patriarch. Over time, the appearance of connection fractures and the relationship is forced into open confrontation.

Love As Masculine Redemption

In films of this kind, women often slip into the background and operate as narrative tools for men to discover that others carry emotions and that empathy is not an abstract virtue. That emotional labour appears repeatedly on screen, blinkingly here too, yet the film doesn’t allow the entire burden of change to rest on them alone. Layered romances unfold in tides throughout Kumbalangi Nights. Baby (Anna Ben) and Bobby, shaped by clashing domestic codes and economic distance, move under Shammy’s constant surveillance. They watch Arjun Reddy (2017) in the theatre and when she rejects his advances, he feels humiliated and asserts himself as “a man.” Kumbalangi Nights also quietly subverts the film playing in the theatre—a woman claiming control over her body, guiding the man with a mix of firmness and patience where he lacks a sense of boundaries. She also becomes the one for whom Bobby finally starts working, retiring from his life of lethargic shenanigans. Elsewhere, Nylah (Jasmine Metivier) grows close to Bonny (Sreenath Bhasi). Their cross-cultural bond stays cautiously named as “dating” when Franky asks about marriage. These defiant attachments turn into reflective spaces where partners confront inherited prejudice and measure the depth of their devotion. Bobby begins to respect consent and vulnerability and Bonny also learns how to stand up for himself and defend the person he loves.

As intimacy becomes their shelter, the couples open themselves to risk, restoration and a steadier sense of who they can be together. It unfolds like the journey of Bunny (Ranbir Kapoor) in Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani (2013), who— struggling with the loss of his father while seeking his own path—must come to terms with the absence and discover what Naina (Deepika Padukone) represents in his life. The impermanence of moments and relationships articulated by his father and Aditi (Kalki Koechlin) along with lessons on “missed sunsets” by Naina, push him toward clarity, courage and commitment. In a more violent turn of events, The Girlfriend (2025) positions a very public dismantling of male ego by Bhooma Devi (Rashmika Mandanna) within the Arjun Reddy-coded hero Vikram (Dheekshith Shetty) as the facade of their relationship shatters. Self-realisation thus sometimes unfolds quietly through love; at other times, it is brutally forced out; yet, it surely arrives to hold up a mirror to the ego.

The Exhausting Theatrics Of Masculinity

The film centres masculinity at its core, making it the most compelling thread in the narrative. Masculinity here has no vessel to pass down, but is to be stitched together from error, tenderness and resistance. Amidst the family’s fragmented dynamics, romantic tensions and moments of despair, the film repeatedly returns to its exploration of what it means to be a man. It portrays distinct facets of fractured masculinity through Saji, Shammy, Bobby, Bonny and Franky—all tracing certain insecurities, violent tendencies, emotional turbulence and parental trauma.

Drawing a subtle parallel, Shammy and the therapist (Ajith Moorkooth) both aim to draw out the inner truths of others. Shammy does so with suspicion, invoking fear and driven by a need to control what he does not know. The therapist, in contrast, seeks only to ease Saji’s burden, creating space for him to speak at his own pace and with trust. One man compels maliciously while the other patiently creates space for conversation without judgement.

In films like these, the question of masculinity hinges on how much a man mirrors his father or deliberately charts his own path. But the Napoleon brothers struggle to understand what it truly means to be a man as the only figure traditionally meant to show them the way is absent. In The Girlfriend, Vikram mirrors the behavior of his absent father in the way he treats his “silent” mother. He tells Bhooma about his mother’s innocence and recalls his father hitting her with a belt with unsettling casualness. This unquestioned reverence for the father figure carries a legacy of trauma, harming both women and men across generations. Alternatively, a son can sometimes crumble under the image of his own father, surrendering to a legacy too heavy to carry. In Gandhi, My Father (2007), Mohandas (Darshan Jariwala) stands as an idealised distant pedestal that Harilal (Akshaye Khanna) cannot reach, withdrawing into alcoholism and staging a different kind of ruin. Contrary to that, a son can sometimes break free from paternal expectations as shown in Udaan (2010), wherein Rohan (Rajat Barmecha) instead pushes against fate and a punishing parent, so his desire to write can finally take form.

Nature As A Site For Inner Negotiation

The idea of self-discovery in films is often linked to travel. One must leave familiar surroundings, immerse themselves in nature and confront their own thoughts to understand their identities and desires. Kumbalangi Nights situates its story within a layered world of characters in a small Kochi village, surrounded by glimmering night-waters, thriving pisciculture and quiet lives. The setting becomes a tender stage for the characters to untangle their emotions, despite years of living there. The film’s very vibrant, contemporary ideas of masculinity and family values take shape not in cities or legends but in the living, breathing textures of rural life.

Architecturally too, the film is deeply interested with the idea of isolation and how masculinity can be alienating, protecting a broken home on a small islet that the villagers called a dumpyard or wasteland. It is where people come to abandon young kittens or puppies and eventually becomes home to a pregnant woman left cornered by society. This isolated space, which once felt emotionally desolate and crumbling, in fact emerges as a sanctuary for those orphaned by fate.

In films like Piku (2015) and Karwaan (2018), the winding road trip through various landscapes emerges as an inner odyssey, especially when Rana (Irrfan) and Piku (Deepika Padukone) get time to themselves around serene ghats to experience some relief within the transient normalcy. Bunny from Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani journeys to Manali, falls for Naina and seeks different destinations as a way to escape his own mind while tasting freedom. In Dil Dhadakne Do, the sea transforms into a space for letting go, confrontation and renewal amid family tensions. Travel and nature in these films functions both as an escape from life’s constraints and as a sanctuary for exploring inner landscapes.

Found Family As An Elixir

In a scene, Baby asks Bobby, “How many mothers and fathers do you have? I need a list by sunrise.” What seems like an innocent question cuts deep for Bobby. They technically have multiple mothers and fathers; yet, none are present to steer them. Inside, they are lost, lacking an inner compass and to the world, they feel incomplete. As Shammy bluntly puts it, they could all be “illegitimate.”

In a world where lost parents cannot be recovered, the brothers must create their own sense of family with the people they choose to keep close. Nylah, Baby, Sathi (Sheela Rajkumar) and Simmy (Grace Antony) reside on the islet as a family. In a home stripped of law and faith, where the presence of mothers and worship has faded, Sathi’s arrival with her newborn appears almost like a living portrait of the Virgin Mary, bringing a fragile grace to the remnants of a once-Christian household.

In many ways, Kumbalangi Nights shows these unconventional orphaned characters building a sense of home through one another and inhabiting a space that was once ruined and neglected. The found family here isn’t merely a shelter. It is a victory—something wrested back from the generational control of people like Shammy. The film lingers in memory as one of the finest Malayalam works, marked by Narayanan’s distinctive perspective and writing that is vivid and resonant.