The 2024 General Elections seem to be shaping up as a battle between ‘One’ India in one corner and ‘many’ INDIA(s) of all sizes and sensibilities in the other.

Months after the grand coming together of the Opposition’s INDIA alliance, consisting of 26 political parties, the collective has upped the pressure on the ruling BJP, attacking it on multiple issues, be it the Israel-Palestine war, NCERT’s recommendation to change India’s nomenclature to ‘Bharat’ in school textbooks or unleashing the Enforcement Directorate against Opposition leaders.

On October 28, Congress leader Priyanka Gandhi Vadra criticised India’s abstention from a UN resolution on Gaza. She also invoked Mahatma Gandhi, urging the central government to take a stand on the humanitarian crisis in Palestine.

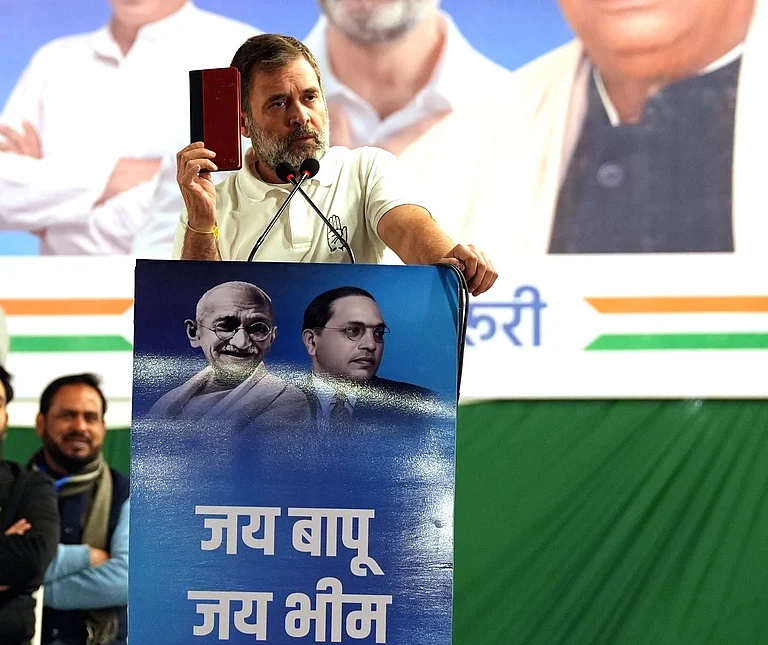

Recently, Rahul Gandhi’s social media blitz featured an interview with Satya Pal Malik, a BJP-appointed Governor of the former state of Jammu and Kashmir, who oversaw the controversial bifurcation of the state. The viral interview with Malik, who has since been critical of top BJP leadership, broached contentious issues like the Pulwama attack and the government’s alleged largesse to the Adani Group. Gandhi’s social media feed is also peppered with videos showing the former party vice-president chiselling tables for students, addressing concerns of carpenters, taking selfies with porters and welcoming puppies into his home. He also biked to Ladakh to engage with locals in remote locales.

Gandhi’s YouTube channel had cooking lessons too, from Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) leader Lalu Prasad Yadav. The former Bihar CM, who once famously wanted to ‘throw the Congress into the Bay of Bengal’, was seen teaching Gandhi how to cook Champaran mutton for a national audience.

Other parties in the INDIA bloc have also recognised the power of social media optics.

Channelling Social Media

The shift in the social media imprint of the Opposition parties in the run-up to 2024 as well as the five key state elections has not been lost on political commentators. “I think, the Opposition’s strategy is quite interesting. They are adopting out-of-the-box techniques. Beating the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance is not an easy feat and the Congress seems to have finally realised the importance of the digital space,” says senior journalist and political commentator Rasheed Kidwai. The party’s social media strategy on social media platforms like X, Facebook and Instagram, uses humour, posters, memes, reels and infographics to articulate its position against rising majoritarian and sectarian politics.

The shift in the social media imprint of the Opposition parties in the run-up to 2024 as well as the five key state elections has not been lost on political commentators.

In October, a ‘poster war’ erupted between the ruling BJP and Congress on social media. The BJP pitched a morphed image of Rahul Gandhi with 10 heads with a warning, ‘Bharat Khatre Mein Hai’ (India is in danger) in response to a Congress barb portraying Prime Minister Narendra Modi as ‘Jumla Boy’, inspired by the Zoya Akhtar film Gully Boy.

The poster war is the latest in a spate of social media attacks by the Congress and Opposition parties on the Modi government.

“In India, air time is very lopsided. The government gets a lot of coverage from mainstream television media. So, the Opposition, the INDIA alliance, has very deftly used social media to reach out to the masses,” Kidwai states.

The Congress, aiming to connect with youth, has partnered with various social media platforms and civil society programmes. Earlier, social media was viewed as the BJP’s domain, but now, Rahul Gandhi leverages X and social media for crucial announcements, a shift from his previous perception of its erstwhile avatar, Twitter, as an “urban fad” notes Kidwai.

Beyond virtual perceptions, the INDIA alliance relies on traditional strategies—caste politics and social justice principles. “INDIA’s strategy is quite plain,” says author Sugata Srinivasaraju. Modi, BJP and RSS emphasise ‘oneness’ in nation, language, election and religion. Srinivasaraju believes the opposition lacks a cohesive ‘oneness’ idea in response. “Instead of striving for uniformity, they aim to build their alliance around India’s diverse fabric, uniting through respect for varied identities and cultures!” he said.

Srinivasaraju observes the Congress rooting for diversity as an electoral strategy, focusing on caste politics. This shift is evident in their recent push for a caste census, promising its implementation if elected in 2024. This contrasts their previous stance for a ‘casteless’ India, historically emphasising national unity during the freedom movement. While local politics often hinges on caste, the party traditionally maintained an official distance from caste-based politics, underlining its role as a unifier for the nation.

Analyst and author V Krishna Anantha asserts that Congress and most mainstream Indian parties have long grappled with the caste issue. “Caste census has revived a kind of a backward class discourse now. But it’s been a part of Indian political debate since 60s and 70s,” says Anantha.

The Janata Party government appointed the Mandal Commission in 1978. Potential hindrance arose in 1980 when its term was midway. Indira Gandhi, PM then, could have halted its work, but she extended the Commission’s term. Despite her successor Rajiv Gandhi’s belief in a ‘casteless’ society, it was a Congress-led government that implemented the Mandal Commission’s recommendations in 1993, following the Indira Sahni case in the Supreme Court of India.

Earlier, social media was viewed as the BJP’s domain, but now, Rahul Gandhi leverages X (Twitter) for crucial announcements, a shift from his previous perception of calling it an ‘urban fad’.

“Till this time, we thought that the OBCs constitute about 54 per cent as per the 1931 census. The Mandal Commission recommendations also worked on the basis of these numbers. Now it’s being revealed that 63 per cent of the population is likely to be OBC. Is it possible for anyone in a democracy to ignore a caste of people’s group that constitutes 63 per cent?” Anantha asks.

The debate over a caste census comes at a time when the BJP is increasingly led by OBCs, including PM Modi. “No party can actually run away from the idea of a caste census,” the analyst asserts. And if caste is the game, the INDIA alliance seems to have more experienced players than the Congress.

While the Congress lacks experience in caste alliances, INDIA leaders like JD(U)’s Nitish Kumar, RJD’s Lalu Prasad Yadav and Samajwadi Party members are seasoned in the intricate caste politics of the Gangetic Plains. Congress struggled in Bihar due to powerful caste-based movements influencing politics.

“What Nitish has tried to do by announcing the caste census data in Bihar is to take over the limelight that was being accorded to the Congress with regard to the caste census. So, the focus is now on him and Lalu Prasad Yadav and other leaders who know that caste game very well,” says Srinivasaraju, who recently authored a book on Rahul Gandhi’s political journey titled Strange Burdens.

Opposition Unity

Political parties uniting against the ruling party is not new in Indian politics. In 1967, the combined Opposition unseated Congress in nine states, significantly reducing its Lok Sabha strength.

“At the time, Opposition unity came about as a consolidation of several poll planks like farmers’ plight, food shortage and growing dependence on US-imported grains among other issues. But between 1969 and 71, when she returned (to power), there was one important development —bank nationalisation —that actually got Indira back,” Anantha explains.

Bank nationalisation, a major reform, was a shot in the arm for farmers during the Green Revolution. Indira Gandhi utilised it effectively, portraying the Opposition as anti-welfare. Nationalised banks offered vital agricultural loans, meeting farmers’ needs for subsidies, seeds and electricity, contributing significantly to her 1971 mandate.

The case of Indira shows that Opposition alliances can only be successful if they manage to identify actual problems or stress points under an incumbent dispensation. In the case of Gandhi, one of the main factors that led to protests against her—the agrarian question—was solved by her policies, rendering Opposition unity irrelevant.

In 1976-77, the JP movement, led by socialists, activists and students, targeted corruption and nepotism, fuelled by discontent with the post-emergency Congress government and the Gandhi family. Muslims felt alienated due to forced sterilisation, while Dalits were disillusioned by demolition drives. These disparate voices coalesced in the Janata Party coalition, whose component, the Jan Sangh, later transformed into the BJP.

The takeaway here is about how ground conditions can make an Opposition alliance successful in ousting the ruling hegemony. According to Anantha, the Janata Party’s success wasn’t due to a credible programme, but the unity in purpose to defeat the ruling party.

“What we must therefore ask ourselves is whether the situation is ripe for a change on the ground. And when in the past the situation was ripe, whether such combinations that evolved on the basis of programmatic understanding or otherwise, had succeeded,” he adds.

Politics offers no guarantees. The United Front’s common minimum programme in 1998 didn’t ensure a win. Psephologists labelled ‘Index of Opposition Unity’ as the critical factor for victory. It’s not just about understanding programmatic nuance but tapping actual public sentiment—whether genuine resentment exists against the incumbent. Success or failure pivots on this vital aspect.

Religious Realities

Analysts and commentators agree that while Opposition unity destabilised governments before, today’s religious polarisation is unprecedented in 30 years. “A large segment of the articulate middle class today is completely consumed by what I call a propaganda war,” says Anantha.

The decisive factor seems to boil down to each contender’s approach to religion and communal politics.

The Congress, seemingly leading the alliance, presents itself as secular, showcasing actions like Rahul Gandhi’s interactions. Analysts note the INDIA alliances’ and Congress’ religious policies stem from political opportunism.

In poll-bound Madhya Pradesh, Kamal Nath who is the face of the INDIA alliance, holds sway as a Hindu leader and does not shy away from flashing his religious credentials. He has even proclaimed that India is already a Hindu Rashtra (Hindu Nation) as envisioned by the Sangh Parivar.

Political parties uniting against the ruling party is not new in Indian politics. In 1967, the combined Opposition unseated Congress in nine states, significantly reducing its Lok Sabha strength.

The Congress is crafting a Hindu narrative, highlighting a tolerant Hindu identity in contrast to the BJP’s assertive stance. This counters Hindutva’s militant Hindu vision. Rahul Gandhi, in a recent op-ed, portrayed Hinduism as an inclusive “ocean” almost adopting a guru-like tenor. Congress aims to present India as a land of benevolent Hinduism, challenging Hindutva’s aggressive narrative.

The Congress’s stance on polarisation echoes a 2004 resolution by the Congress Working Committee (CWC), which asserted Hinduism as vital for national secularism. While upholding their ‘secular’ stance, leaders like Rahul and Priyanka Gandhi frequently visit temples. Unlike his great-grandfather and grandmother whose positions on religion were atheistic or ambivalent, Rahul Gandhi portrays himself as a self-proclaimed “believer” in Hinduism.

Anantha retells an anecdote to put the Congress’ ideological shift in context.

“Once Mahatma Gandhi had asked Ram Manohar Lohia if he believed in God to which the latter had vehemently said no. The Mahatma reportedly gave him a mischievous smile and said nothing,” he says. A decade later, Lohia recalled the conversation and said that he finally understood what Gandhi’s smile had meant.

“He understood then that if you go to the people and tell them that there is no God, the people will stop listening to you. Whether you believe in God or not is not central, but if you tell them that you don’t believe in God, your communication with them snaps,” Anantha adds.

Rasheed Kidwai nevertheless feels that at this point, there seems to be a “cynical desire to beat the BJP and Narendra Modi at any cost” at play among the Opposition. “All the 20-plus parties that have banded together to form this alliance are able to swallow a lot of humiliation and bear the brunt of the ideological sharp edges that exist between INDIA alliance partners,” he states.

It’s premature to predict the alliance’s success in resolving differences and shaping next year’s political narrative. Observers like Kidwai, believe the Opposition has finally been able to set the tone, a first since 2014. “Since 2014, Narendra Modi was setting the agenda or the political narrative. He had the upper hand and made the offensive while the Opposition was forced to follow it up and come up with a hasty, knee-jerk response. There was chaos. Now there is a semblance of normalcy, cohesion and equality among the Opposition parties,” Kidwai observes.

For once, it appears that the Opposition may have finally set the feral cat amongst the pigeons preening in the corridors of power.

(This appeared in the print as 'Is The Coalition Ready?')